Periodisation for Teenagers

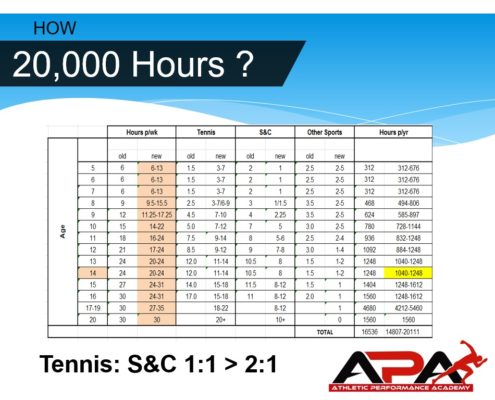

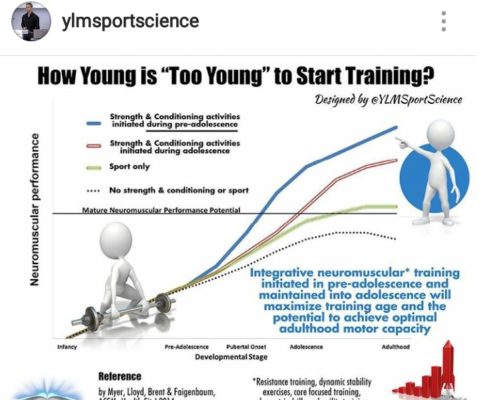

This week I had a few comments from parents who were concerned about their children lifting weights. I also had a great meeting with a tennis team about the annual plan of a 13 year old boy and discussion of his strength & conditioning goals for the year.

It’s funny how various coaches I admire and share ideas with can be thinking of the very same topics as I do- but then I guess it’s no surprise as we are constantly all looking to answer the same question- namely how to maximise athletic performance.

Only this week two of my favourite S&C bloggers Eric Cressey and Matt Kuzdub released blog posts on topics that relate to these very issues! Cressey Sports Performance (CSP) coach, John O’Neil wrote a three part series on Periodisation for Teenagers which is the inspiration for this blog, and Matt has been putting some great ideas out on how to apply the Force-Velocity relationship to Tennis Training

Why we need to Lift Weights

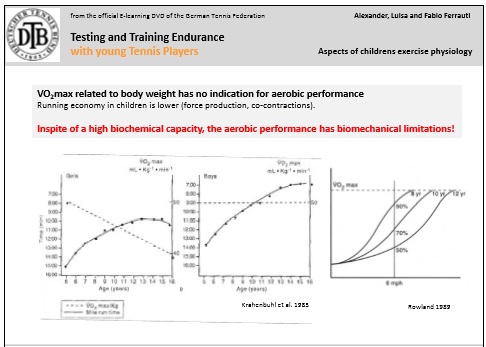

I never feel disappointed that I have to answer this question so many times because I totally understand why parents may have initial concerns. But once you look at three facts it can be easier to get the parents to come around.

1– Olympic weightlifting is one of the safest sports on the planet- less injuries per 1000 hours reported than any other sport. Resistance training per se is very safe.

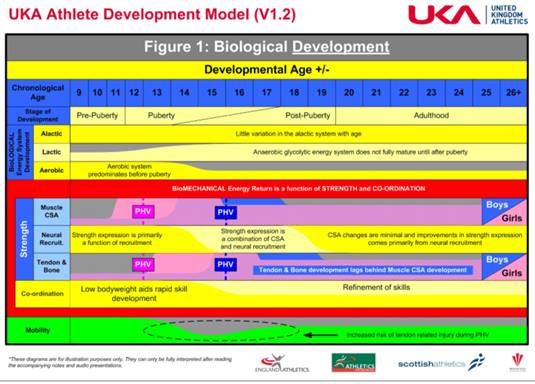

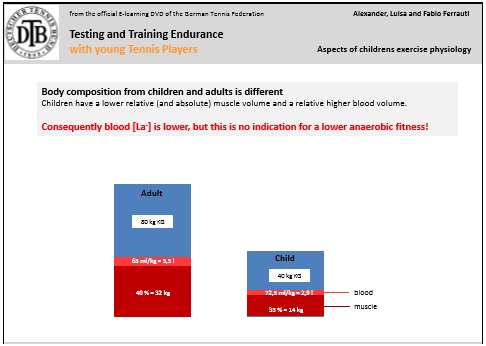

2– There is no scientific data that it has adverse affects on growth and development. In fact any observable physical changes such as muscle mass increase can only be a good thing for protecting the tendons, and ligaments. Bone density will increase through impact from controlled landings, where we teach children to absorb forces properly. Furthermore, flexibility will be enhanced with appropriate full range lifting techniques.

3– Newton’s Law of Motion

Remember Newton’s 3rd law? For every action, there is an equal (force) and opposite (direction) reaction. Therefore, the more force we apply to the ground, the more force will be exerted- meaning we can move more explosively around the Tennis court! You can only apply so much force into the ground with your bodyweight. To apply more force you need to work against weight of external resistance- the kind you stick on your back when you squat, for example!! That’s why weight training works. It makes you have to apply more force to stand up! But what’s really cool is that if you lower that weight carefully it teaches you to absorb more force as well!

As Matt says in his blog, ”In tennis, max strength is critical to both absorb high forces and to generate high forces. When referring to the absorption of forces, the most common scenario in tennis is deceleration. The higher the running speed before setting up for a ball, the faster will be the rate of deceleration and the more force the lower body must absorb. Eccentric strength is vital in this scenario. If you think about decelerating when tracking down a ball, you can associate that with the deceleration phase of a heavy squat. Strength adaptations are joint specific, contraction specific and speed specific. Believe it or not, deceleration in sport and the lowering phase of a squat have similar characteristics.

There are even cases when more than 2-3 times a player’s bodyweight is acting on them during deceleration tasks…if they can’t handle these loads in the gym, they surely won’t have the ability when it comes to the tennis court. ”

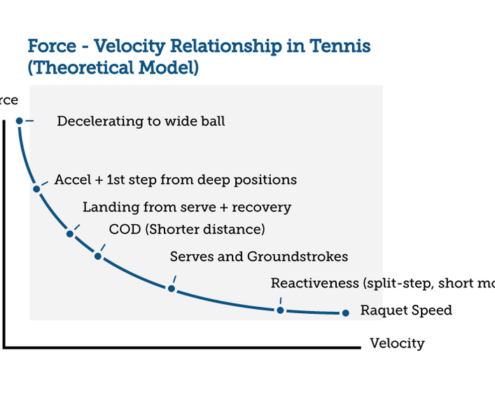

Figure: Courtesy of Matt Kuzdub

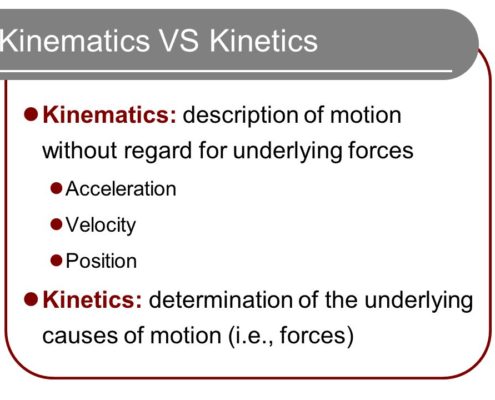

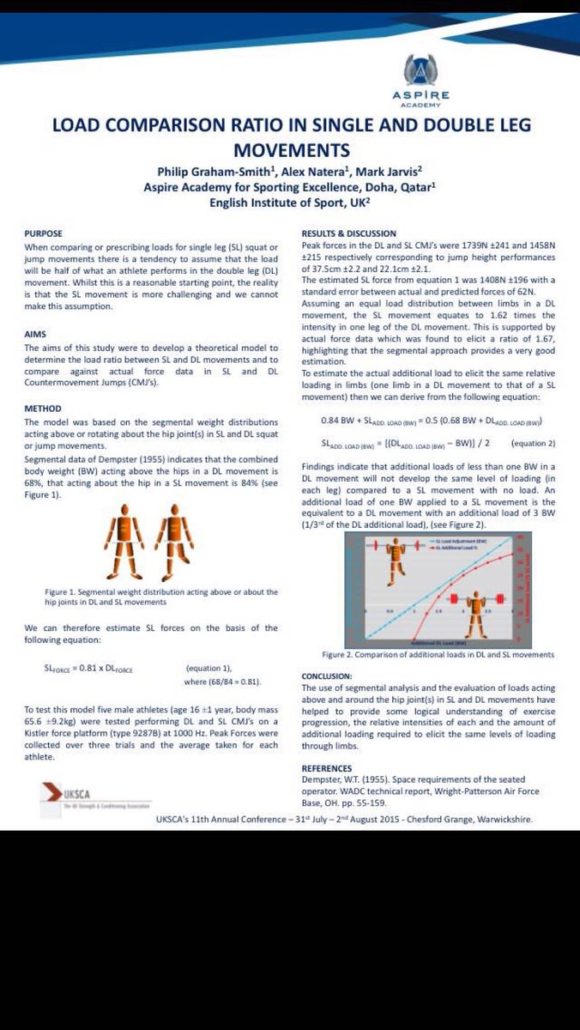

In any plan we are really trying to develop the ability of the athlete to express different degrees of Force and Velocity according to the demands of the sport. Whenever I work with my interns one of the first exercises I get them to do is think about where different types of tennis movements fall on the F-V curve. Matt has done a great job of highlighting the main ones above.

Furthermore, during each movement, different parts of the the F-V curve could be involved. For instance, when hitting an open stance forehand, strength-speed qualities would predominate when initiating the leg drive, while once we get closer to contacting the ball, we move down the curve into higher velocity segments.

Bottom line- we are looking at increasing the force generating and force absorbing capacity of the body!!! This is vital because the tennis player is exposed to these every time they step on the court. We have a duty of care to prepare them for these loads by enabling them to experience these loads in a controlled safe environment- rather than just the high stress environment of the court!

So we have to do a great job of educating the parents (and coaches and athletes!) that strength training which includes lifting weights- is the most effective way to increase the force generating capacities of the body.

But isn’t bodyweight training enough?

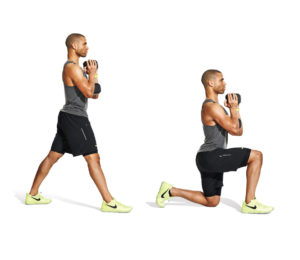

A parent recently said to me that body weight training is more than enough for their pre-pubescent child to get strong. I actually couldn’t disagree with this comment in the context of her daughter’s current development. She is just starting her S&C journey. The bodyweight squat is the first step in a progression which follows on to a goblet squat and later barbell squat as we see here in this example.

I will touch on this further in the main topic below. The key thing to remember is that bodyweight training is not going to prepare the body for the stresses of sport which are often several times bodyweight. But the real key point is who says you have to wait until after puberty before progressing to external resistance? This is a belief which is perpetuated on a myth that resistance training is unsafe for children. As I said earlier, there is no scientific data that it has adverse affects on growth and development.

When we determine what the most appropriate resistance should be for an athlete (of any age) we need to consider whether they can:

=> perform the activity with perfect technique

=> perform the activity with the required tempo- meaning under control

If a child of 11 has already developed their technique in a given athletic skill with bodyweight and we determine that they can continue to meet the above criteria with an external load, then there is no reason not to add this, assuming that the bodyweight exercise is no longer proving challenging!

How we Periodise for Teenagers

One of my favourite books of all time is ‘Special Strength Training for Sports,’ by Yuri Verkhoshansky. In the preface he mentions that the goal of his methodology is to allow the athlete to execute his or her specific competition exercise with greater power output using a ‘conjugate-sequence system’. This basically means the goal is to be able to be more powerful at the movements you actually perform on the court!

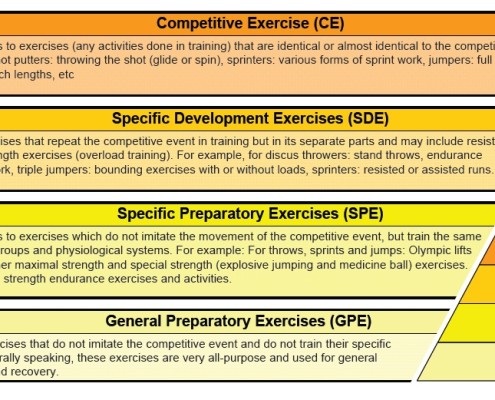

Much of his research has been applied to elite athletes who are very advanced, and most of those athletes came from the sport of athletics. He talks about a conjugate-sequence system. To better understand this we need to define some terms.

Definitions:

Concurrent?

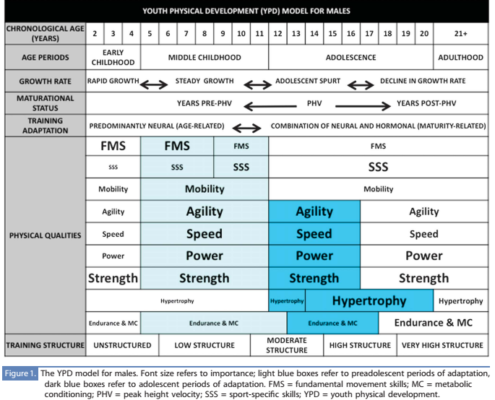

Taken from Supertraining (Siff, Verkoshansky), a concurrent model “involves the parallel training of several motor abilities, such as strength, speed, and endurance, over the same period, with the intention of producing a multi-faceted development of fitness.”

Conjugate?

You might of heard of this term in languages or even maths. In a strength & conditioning setting it means a form of periodisation (planning) where we build ‘connected‘ components of fitness on top of one another.

adjective

-

1.coupled, connected, or related, in particular:

A conjugated sequence, as defined by Periodization (Bompa), is a “method of sequencing training to take advantage of training residuals developed within periods of concentrated loading.”

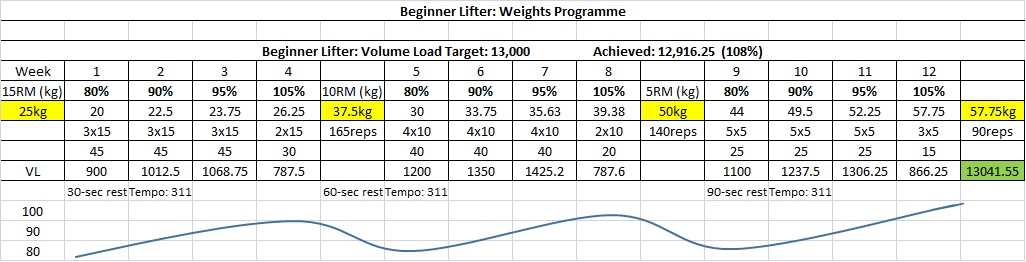

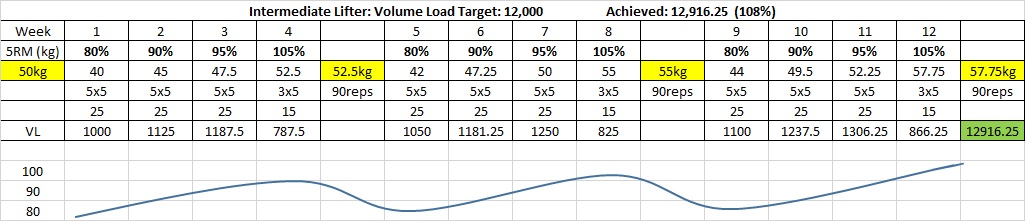

In terms of ‘sequencing’ we need a plan which takes into account the sequencing of exercises from two standpoints- the fitness component(s) you are emphasising for a given time period (time) and the intensity of the exercises used for that fitness component (intensity). I refer to the time period as the ‘X’ axis and the intensity as the ‘Y’ axis.

Y axis: So what exercises come first in a sequence?

As alluded to above, there are always two elements to factor in when making any plan- what I call the ‘X’ factor and ‘Y’ factor.

The Y factor- for a given type of fitness (let’s say Strength) we need to choose the most appropriate ”intensity” of exercise. The least intensive forms of exercise are close to the X axis. The most intensive forms of exercise are furthest away from the X axis. X axis – is duration (stage of development).

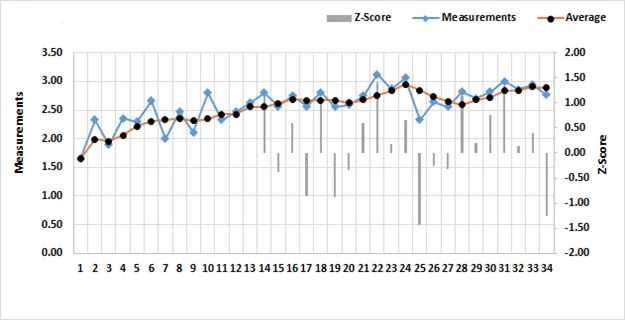

Verkhoshansky deduced that training means with the ”same” training direction (meaning exercises that work on the same type of fitness- in this case strength), but different training potentials, should be incorporated into the training plan in a definite sequence. As it relates to novice athletes, this sequencing relates to progressively increasing the training intensity (Y axis) of exercises over time (X axis)

In order to determine an exercise’s place in the sequence you need to know about its training potential.

Think of it like filling up your fitness bucket!!

Every exercise has a training potential- the capacity to increase an aspect of an athlete’s fitness towards its motor potential (a full bucket). It is more suitable to use the training means with lower potential first, followed sequentially by those having a high training potential.

So going back to our bodyweight training concept these exercises have the lowest training potential and represent the start point of a training process. But once these exercises can no longer provide an adequate training stimuli it is time to add external resistance. Remember also that we adapt to different exercises at different rates- we might find a press-up or a pull-up really hard for many months and even years!! But a bodyweight squat which uses the strongest biggest muscles of the body might become easy after only a few weeks!!

For any athlete, it is not appropriate to use high-intensity training stimuli (training means having high training potential) at the beginning of the training process– since the body is not yet ready!!

For young athletes, and those with less training history, the training is aimed not only towards improvement of their performance in current competitions, but also, and above all, to their preparation for highly intensive and specialised training in the future. You don’t need to give your ace cards away with young athletes. Training exercises with lower potential will still cause an adaptation to the body with novice athletes.

They will adapt and respond to exercises with lower training potential. Over time we will need to gradually substitute these exercises with new exercises having higher training potential.

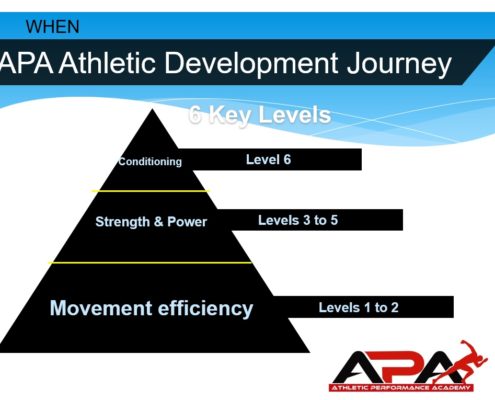

At APA we describe exercises on a continuum of Basic to Advanced. The goal is to progressively introduce greater amounts of Advanced exercises into an athlete’s training programme.

X axis: What should be the focus at different times of the year?

In terms of the focus of the training for the year we need to refer back to Matt’s explanation of the Force-Velocity curve and the article by John O’Neil. With a beginner the bucket is practically empty in all aspects of Force and Velocity. You have heard me say time and time again that at APA we train fitness components concurrently, meaning we train everything all of the time, speed, power and strength.

This is where we refer to the ‘X’ axis. What are the fitness components we want to emphasise at different times in the year? With younger athletes we tend to give them a bit of everything at all times of the year.

Complex sessions for Beginners:

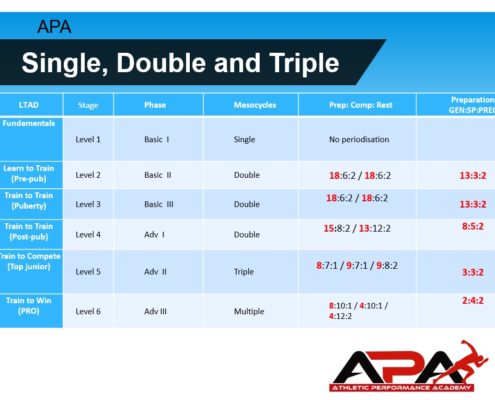

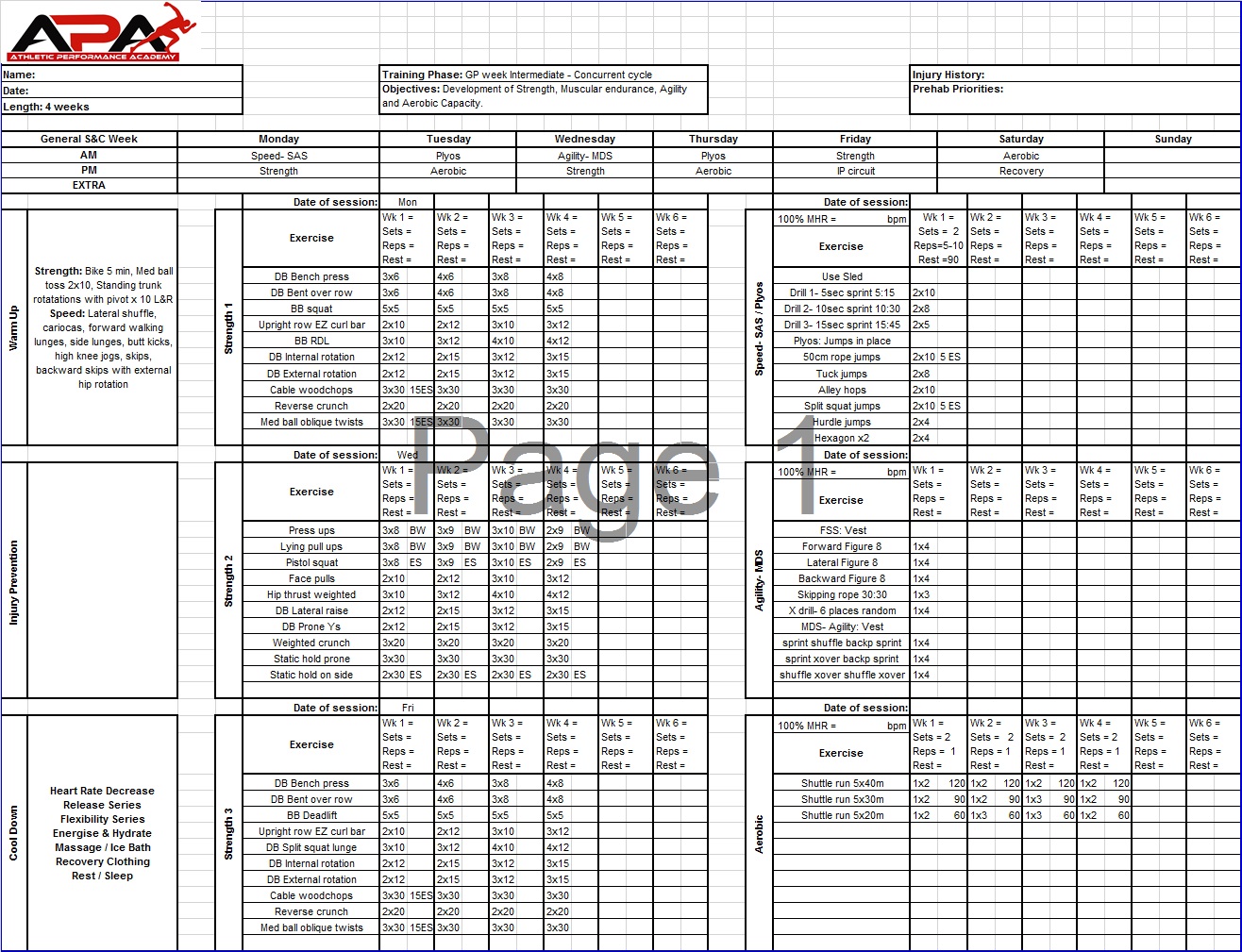

Programming for these athletes won’t have anything resembling a block- where we focus on just one component at the exclusion of others; instead, it will focus on mastering the fundamentals of training so that by the time they’re able to have higher levels of output, they won’t need to spend immense amounts of time learning technique. So in terms of an annual plan we might stick with similar exercises and themes for 12-16 weeks- just manipulating the sets and reps, gradually building intensity and reducing volume. I refer to these as ‘complex’ sessions where in a given session and a given week they will do a bit of speed, a bit of power and a bit of strength.

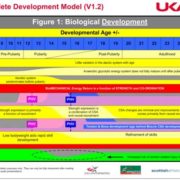

What will change is the category of speed (as an example) that we focus on so in a typical year we might move through speed in the following way:

=> deceleration skills => straight ahead speed => first step speed => sport specific speed (footwork)

Cressey Performance train their teenage athletes this way too.

”At CSP, we use a concurrent/conjugate style of programming that doesn’t strictly adhere to principles of block periodization. The more advanced an athlete is, the more their program might look like it’s block periodization.”

”The reasons are simple: we train primarily athletes who need to train a multitude of qualities in off-seasons ranging 3-6 months – and they don’t need to be peaked for any individual event. Rather, they need to be ready to perform for periods of greater than half the calendar year.”

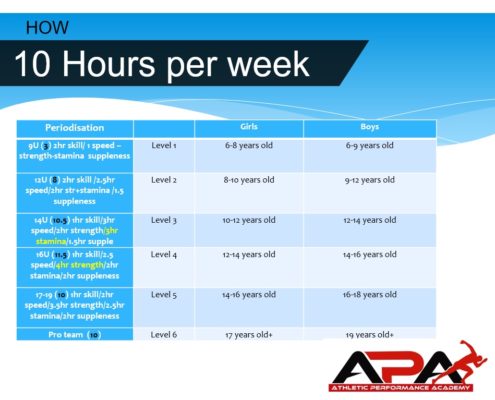

[Caveat: having said that with full-time athletes 13-16 years who I work with in various Tennis Academies they are doing 10 hours of S&C per week. So in that situation I do cycle through blocks of work that have a slightly different focus moving from volume to intensity emphasis over the course of the 12-16 weeks- so for full-timers it has a bit more of the feel of the conjugated model that advanced athletes do below- but the phases are more focused on learning skills. So we might move through a block that emphasises endurance=>strength=>power=>power endurance. But when we get to strength and power for example it just means we do more skill development work in these areas.]

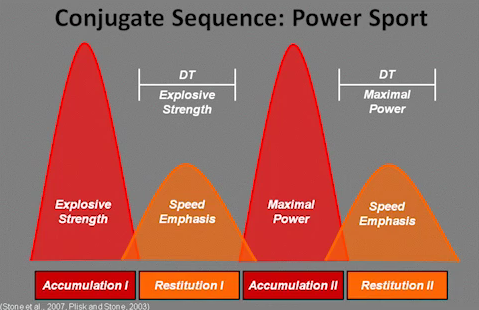

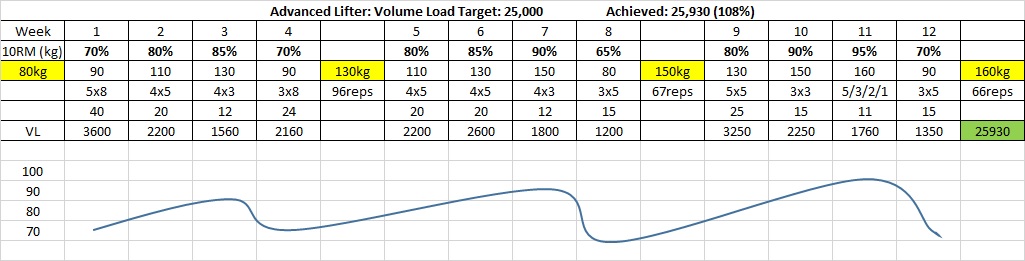

Conjugate sequence for Advanced athletes?

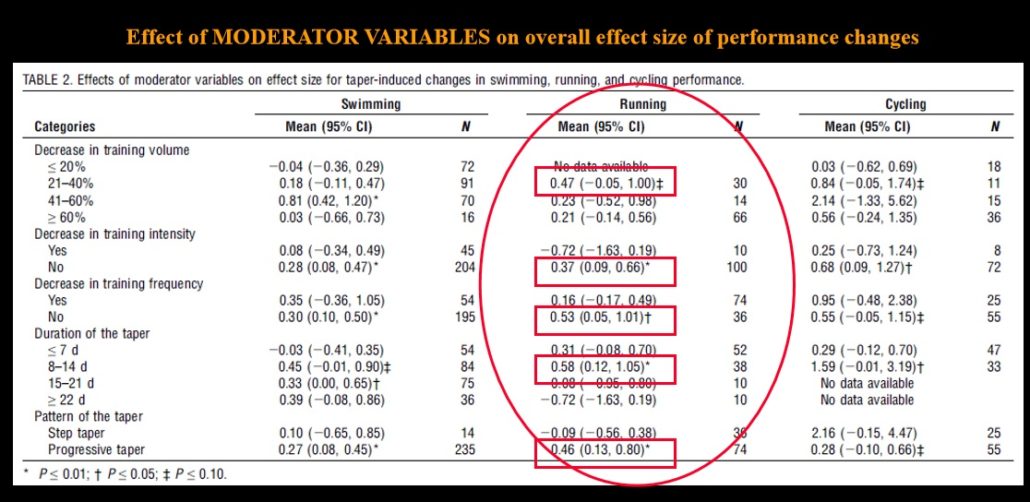

The strategy with more advanced athletes can be a bit different. The specific strategy will be based on the length of time you have to prepare for a competition. If it is a sport with only a few major competitions in the year you might see a strategy which is based on focusing on only one thing at a time, before moving onto something else.

Sports with long preparation periods

Verkoshansky deduced that training means with ”different” training directions could be concentrated in different stages of the preparatory period, incorporated in the training plan in a definite sequence, which had a cumulative effect. He found that the sum of the individual parts added up to a greater effect when you add them on top of each other separately, rather than training them all at the same time.

Cumulative effect of exercises with different training emphasis

So in a typical training period you might progressively work on one theme at a time:

=>increase ability of athlete to produce a maximal strength effort (barbell exercises)

=>increase ability of athlete to produce a maximal strength effort in minimum time (jump training)

=> increase ability of athlete to perform specific exercises and technical event work (technical work)

Weight training is proposed by some to negatively influence speed of movement and it is fair to say that if you do it at the exclusion of other types of fitness for a prolonged period of time, this might be the case. But special strength training (SST) is characterised by the use of training means (exercises) integrated into a system- a training process or ‘method’ to enable the strength increases to transfer into competition exercises in later phases. You do the heavy strength training (or explosive strength in example above) in a concentrated block furthest away from the most important tournaments (which may have the possibility of causing a feeling of ‘heaviness’ in the muscles). But after a period of reduced volume of strength training following the next power phase, you get supercompensation and a long-term delayed training effect (LDTE).

Sports with short preparation periods

For sports like Tennis and Baseball, I personally would go along with Cressey Performance where we don’t do strict ”block” phases with advanced athletes (only training one quality at a time like the original application of the Special Strength training method).

According to Cressey Performance, ”Rather, it is more conjugated- conjugate periodization will have one main focus but will also be training other qualities as supplementary work. The way I do this is adjust the blend of speed vs power vs strength exercises in the session.

When someone is more specialized, the programming will become more of a conjugate model. Exercise selection will be more geared towards training qualities needed for the specific sport. We might change loaded supplementary exercises more frequently to give athletes more exposure to joint positions they need to be strong in, and, each phase will have a specific focus.

Exercise selection, while more variable and through a much wider selection than the beginner athletes, will all have a specific purpose that relates back to performing at their sport. Instead of changing intensity/volume primarily and exercise selection secondarily, the intensity/volume will be scaled directly with the offseason of the sport. The exercise selection might vary more because we don’t want our athletes to become specialists at exercises they can load exceptionally well like deadlifts and squats.”

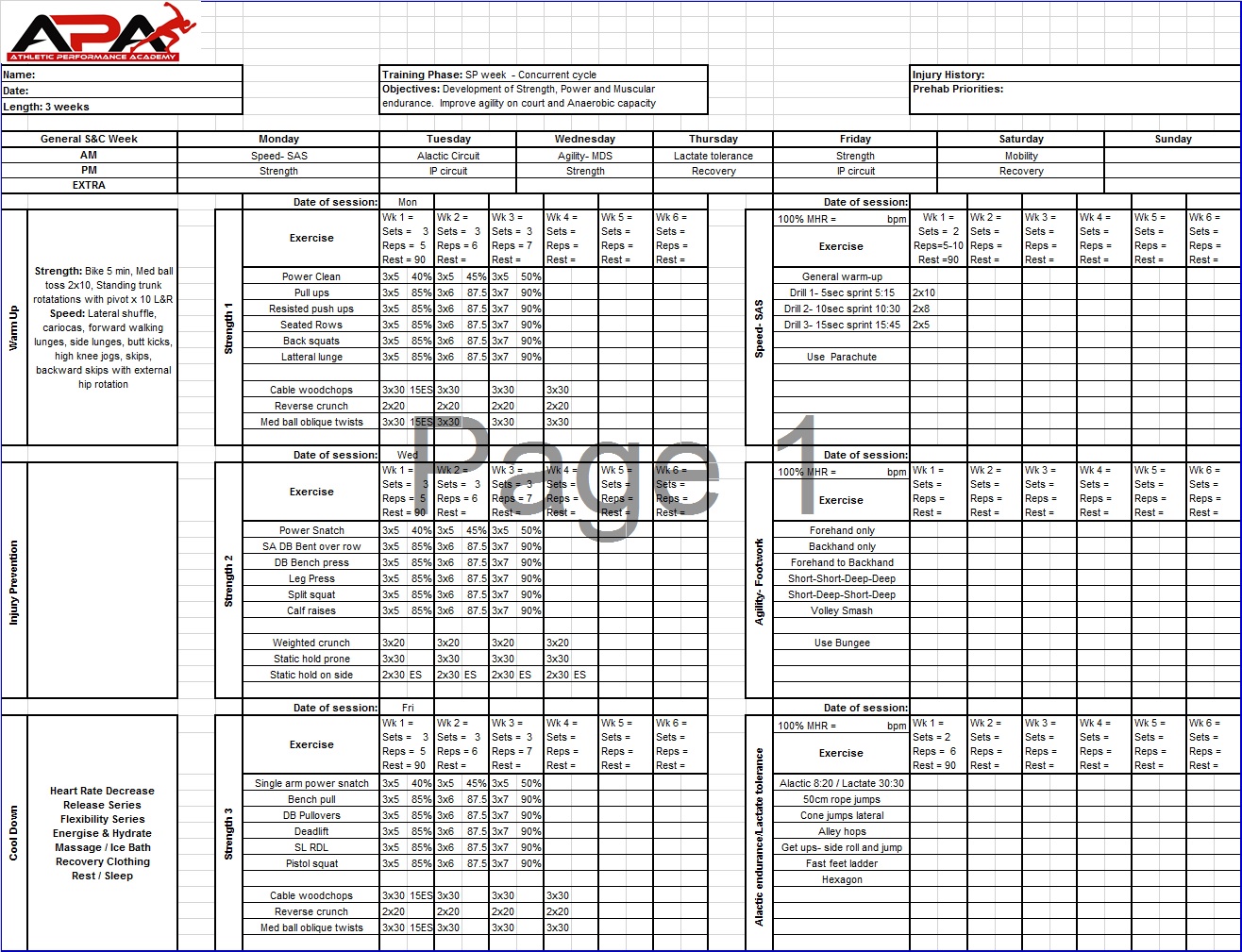

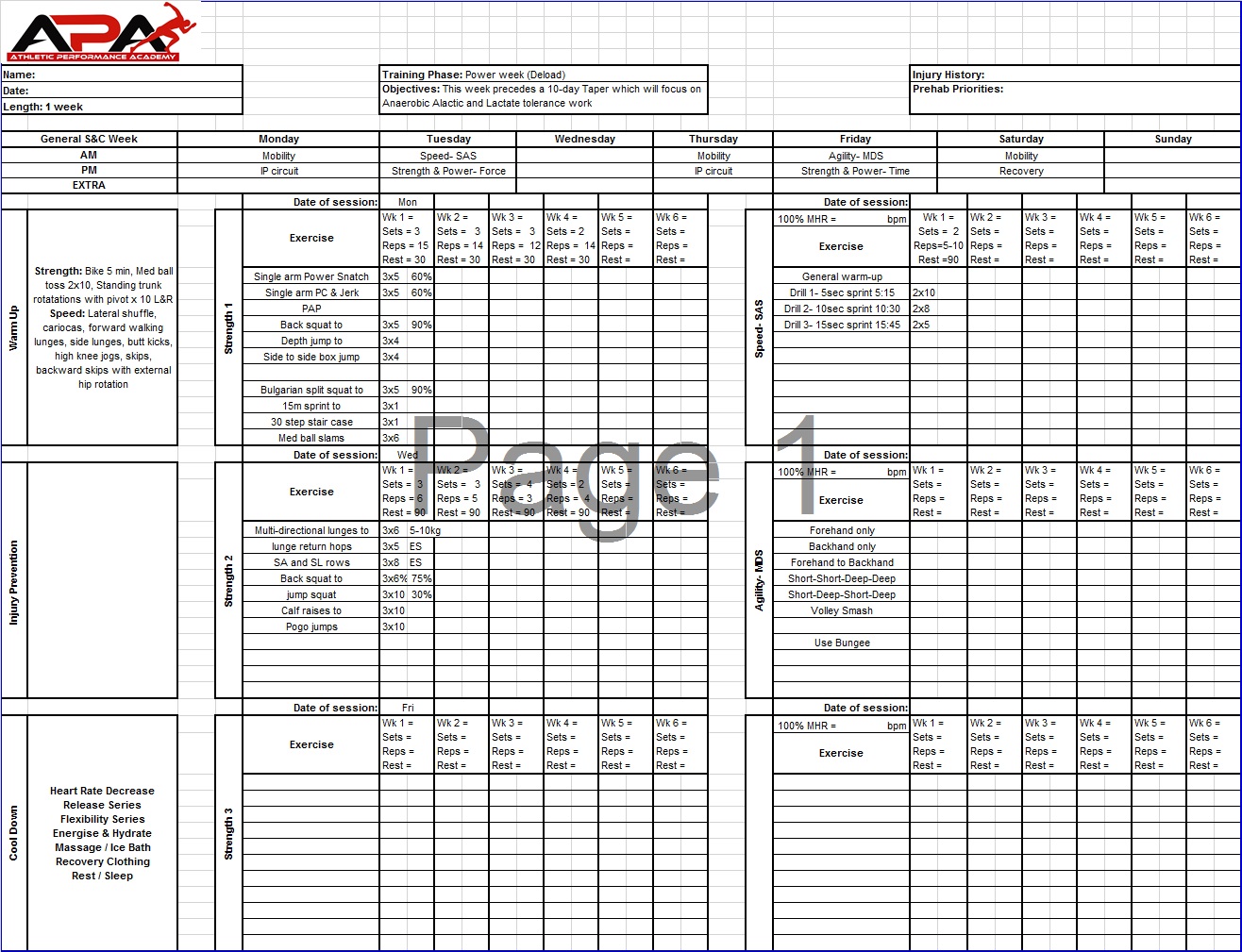

Application to the APA Method:

A max strength focused session as part of the early preparation phase (General prep) might have only one power exercise in the routine and the rest of the plyos would be low level exercises done in a separate session. A power focused session (Specific prep) might have several power exercises and a low volume of Max Strength to maintain it. This is how I develop the squad routines for our pro athletes.

Pre-season essentially the same approach but because we have several sessions per day and lower tennis volume we can afford to separate the strength and power sessions and give them more concentrated doses of both. But the focus will still be determined by the needs of the individuals. Our younger pros 16-18 years old with still do more max strength work. Our seasoned pros with good training history will do more of a mixed routine.

Want to hear more?

I also have the following speaker engagements planned:

Coordination and Strength training for Sports

Dates: 29th October 2017 09:00AM-12:00PM Location: Gosling Sports Park, AL86XE

Tennis Fitness, Sport Science and Coaching Conference

Dates: 9th December 2017 09:00AM-12:00PM Location: Sheffield Hallam University Collegiate Crescent Campus, Sheffield , S102BP

Book your ticket HERE

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM