This blog is a return to my usual review format of the Pacey Performance Podcast.

Episode 442 – Damian, Mark & Ted – Integrating deceleration training and testing into a high performance programme

Damian, Mark & Ted

Background

This episode of the Pacey Performance Podcast sees Rob speaking to Damian Harper, Mark Jamison and Ted Rath. This episode was recorded in the summer of 2021 as a Live roundtable. But it was that good that we had to release it as a podcast.

🔉 Listen to the full episode with Damian, Mark and Ted here

‘‘From a research point of view, Damian, what do we know about deceleration and why is it important?”

Damian Harper:

”I think it’s a really important area, and one which has largely been overlooked. Over the last few years there has been a big impetus to drive some better understanding of this task. When we look at deceleration from a movement outcome, we are typically looking at trying to improve the athlete’s ability to reduce their speed with respect to time.

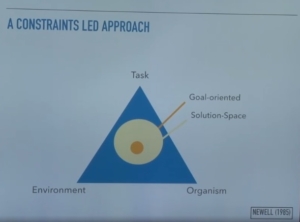

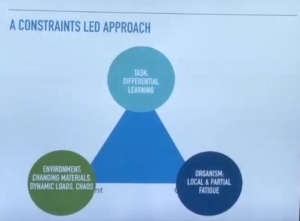

We want to increase the athlete’s ability to get high rates of deceleration from a movement outcome perspective, but it is also important to look at deceleration and braking as a movement skill. With deceleration it is a really complex movement skill and I think we have got to acknowledge that. That ability to be able to coordinate the limbs to apply a braking force, and once we have applied the forces, being able to safely attenuate the forces during deceleration.

Forces and Frequency

So when we look at those two components – the movement outcome and the movement skill we have recently proposed a definition based on those two factors, that deceleration should be considered as:

”the ability to reduce momentum in accordance with the objectives of the task and the constraints, whilst skillfully attenuating and distributing the forces associated with braking.”

So we have highlighted those two components – the braking force control – the ability to control braking forces. but then also the ability to be able to attenuate those braking forces.

It is important to start from the game perspective and look at the demands of the game. In some of my early research we looked at the game demands of accelerating and decelerating at high intensities in games and what we actually found was quite surprising, that in most team sports when we monitored it with GPS above a high-intensity threshold, most team sports had a greater frequency of high intensity decelerations than high intensity accelerations.

In addition to frequency, we also looked at the forces, and the mechanical demands. This is where deceleration becomes really distinct from other movement actions, and we could probably say that deceleration is the most mechanically demanding task from a force and loading perspective.

If we are backwards engineering in terms of demands, then we need to prepare athletes and in particular team sport athletes for these demands and high forces. We are looking at up to 6 x bodyweight in some of the braking forces and that’s in really really short periods of time less than 50 milliseconds, so really high loading rates and really high magnitudes of forces that have to be 1) produced and 2) tolerated and attenuated throughout the lower limbs.”

”Is deceleration training getting the time in the programme that it deserves?”

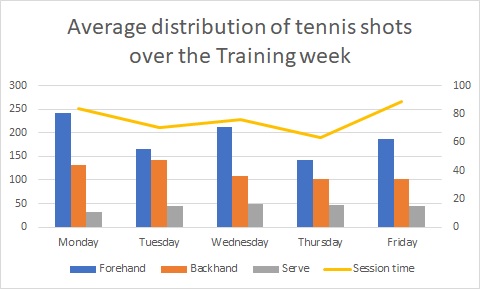

”It is going to be sport specific as if you look at football in the UK, small-sided games, medium-sized games, large-sided games are very popular training methods throughout the training week, and those type of training activities do expose athletes to a high frequency of decelerations. However, what I think we perhaps haven’t got a good as knowledge of is how we can actually improve the coordinative elements of the task, and how we can improve the athlete’s ability to perform those decelerations, outside of those game scenarios, like we have done for acceleration, with resisted acceleration work for example, and other exercise types for acceleration. We are still developing knowledge in this area.”

”Let’s bring in Mark to talk about testing for deceleration. What options have we got and is this an area that is developing?”

Mark Jamison:

”Probably when we have been trying to quantify the braking forces, it has traditionally been in the return to play process, as you are slowly trying to progress those demands over time, and not just the braking forces themselves but the directional pattern of it. I think we did a lot of that in the return to play setting but I don’t think it’s been as popular in the team setting, because I don’t think there has been as much access to good technology or a really efficient way to test in a full team setting.

The first thing we look at when we do any testing or assessments are what are the metrics that we are looking at that become actionable. What are our key performance indicators (KPIs) for this movement, that are actually going to help drive the decision making process when it comes to making interventions or the programme itself.

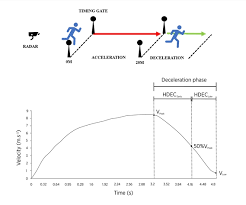

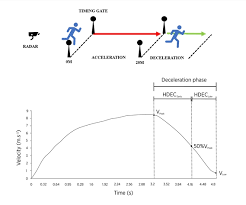

Really, when I look at it from a deceleration standpoint and you are going to do some kind of assessment, what’s the deceleration distance, what’s the deceleration time, what is the rate of deceleration (that’s a difficult thing to test). We have been fortunate as we have a radar timing device that actually gives us the rate of deceleration, so we can actually see what the ”braking impulse” is. Then we can look at early vs. late, so is it a safer strategy, so more time spent in that early deceleration, or are they truly coming from a really high entry velocity and braking really quickly? So those are the things we look at from a deceleration standpoint.

But most of our movements are never a true dead stop so a lot of it is built within change of direction testing. We have always done a 5-10-5 and t-test and L drill and I don’t think we’ve ever really looked at it as deceleration, we look at what’s the total time and what’s the speed of how fast you can do those drills. We really need to look at the braking strategy- how well do they decelerate and what does their re-acceleration look like? We have our deceleration KPIs and our re-acceleration KPIs, so what’s the re-acceleration time and what’s the rate of that re-acceleration?

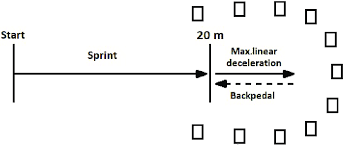

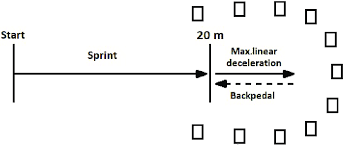

From a testing setting, from a team standpoint, it is a little more difficult but the Acceleration Deceleration Ability (ADA) test is probably the easiest one to do in a full team setting.

We will have our athlete’s sprint for 20 yards and they don’t brake until 20, and it’s really easy to track what was their deceleration distance. Time can be a little more difficult so obviously you’ll probably need some kind of video analysis to determine the time of the deceleration braking was, but you’re always going to have that deceleration distance. Then you can provide different training interventions and ensure that they are actually responding well to that stimulus and improving. so at least we can then work out are they shortening that deceleration distance over time?

That’s easy to do in a team setting, but what is more difficult to do is determine what was the entry velocity. In a pre-determined test they know they have to brake at a certain point, so they are probably not going to hit their highest entry velocity. What we have found with our testing devices, is that when we do the ADA test, typically we are looking at 85-90% of peak velocity coming in, so it’s not a true max test. I think it’s difficult to make it a max test when there is a predetermined braking spot.

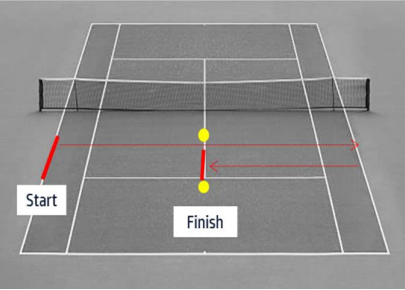

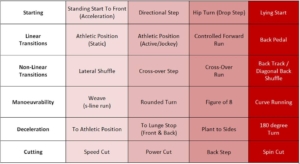

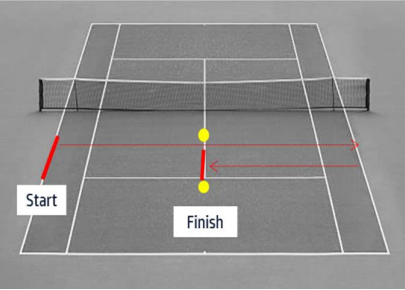

A lot of what I really like to do from a deceleration standpoint is a 10-5 and a 15-5 change of direction test, so a 180 degree cut, start with a 10-5 (usually the entry velocity is around 70-75% of their maximum velocity) but we see from a safety point of view, there’s less braking forces with our testing devices (-5-10 feet/sec 2) as the rate of deceleration (1.5-3.0 m/sec 2) and then we get to a 15-5 change of direction test, now we are touching more closely to that ADA test, so around 85% max velocity, and now the rate of deceleration is much higher (-10-15 feet/sec 2) so pretty high (3.0-4.6 m/sec 2). We can dictate what is the re-acceleration pattern, what movement strategy are we going to provide and then take a look at what is the limb to limb symmetry on that, are there any movement limitations in terms of sprint to a backpedal, in terms of turn and sprint, crossover to sprint, and those different types of movement category selections they have. So then we can look at what are the buckets we need to fill and look at from a movement intervention standpoint.

Example of a 10-5 (known as a modified 5-0-5, as used by the Lawn Tennis Association)

Daz comment:

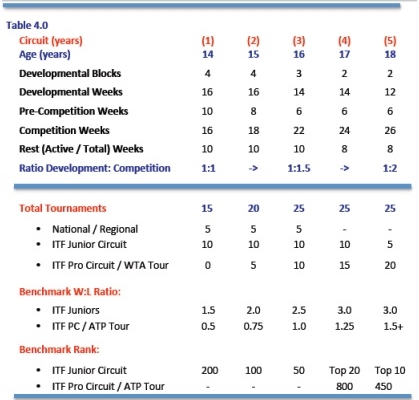

Based on Graham-Smith (2018) research, he mentions ‘’it is important to put the changing of direction movement into context. The maximum speed that an athlete can attain prior to changing direction dictates how much braking impulse needs to be imparted. In game scenarios there is no specified ‘approach’ distance, so in order to understand the loading demands we first need to evaluate the athletes’ ability to accelerate and decelerate within set distances. I refer to two of the distances he tested:

• 10m from stop line – 5.8 m/s –> (72.2% of 30m MSS) –> -4.94m to stop

• 15m from stop line – 6.7 m/s –> (83.0% of 30m MSS) –> -6.61m to stop

At the Lawn Tennis Association, they use a Modified 5-0-5 (so it’s more like a 10m approach) with a total distance of approximately 10m before performing a 180 COD to the finish.

Now back to the Podcast review……

A test that I really like to do, which we have just started doing, is add a chaotic change of direction with a predetermined deceleration test. So we go out to 80 feet (26 yards) and when the device cues them they sprint and go out and hit their max velocity. They don’t know exactly when they are going to have to decelerate and re-direct and go back to the device. We give them that cue whether it is auditory or visual, but what we have seen is closer to 95% of max velocity on that brake itself so those impulses are significantly higher and we get a pretty good indication of what their max potential of deceleration is from that and it’s usually somewhere between 15 and 26 yards and when they sprint back they actually try to decelerate exactly on where the start position would be.

On the chaotic version the distance is always going to be variable which is a huge limitation, but I know the entry velocity, so ideally if I can get as close to above 90% max velocity I think it’s a relatively valid test. So far, if it’s less than 90% I void it, and don’t count it.

The strategy changes quite drastically according to entry velocity. In a 10-5 you really don’t lower your centre of mass much. Your total range of motion on the braking strategy isn’t really that great. When you look at when they are hitting closer to 90-95% of their maximum velocity, they really have to drop their centre of mass to receive and brake those forces and re-direct them so you see a huge level change. Especially on the chaotic version, you start to see more poor kinematics because they don’t know when they are going to brake so they are not preparing for it. You see a lot more excessive forward trunk lean, they are throwing their torso way out in front of their centre of mass, which is obviously going to lead to a high risk of injury. But that’s good to know, because hopefully we can address it a little bit better in the kind of drills or interventions we use to try and train that.”

Damian Harper:

”The entry velocity completely changes the deceleration strategies and it’s a much harder task than acceleration, to be able to get a reliable deceleration assessment of the athlete. The importance of being able to get the peak velocity the moment when the athlete starts the deceleration is critical for any reliable assessment of deceleration capable – the ability to know when the athlete is starting to decelerate.

We can start to look at the ratios between their acceleration ability and their deceleration ability to get some kind of understanding of where there may be training deficiencies and whether they can slow down what they can speed up. Research on cheetahs showed that they had a 60% buffering capacity, meaning that their deceleration capacity was 60% greater than their acceleration capabilities. I think that is very interesting and it is going to vary with different sports and different positional groups.”

”Physical qualities needed to improve it?”

Ted Rath:

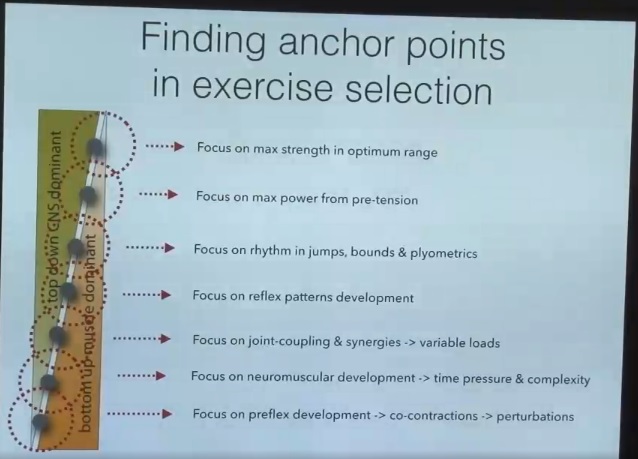

”When you look at deceleration, what is the ultimate factor that accounts for a lot of it? It’s motor control, what is your ability to control your centre of mass. You could have limitations because of joint structures, strength deficits, so for me it’s the opportunity and the ability to decelerate your centre of mass and properly put it in the correct position for your next movement. Once again, what’s the goal, the deceleration goal, to get you into position for your next movement so you can re-accelerate and apply force into the ground and whatever direction you are attempting to go. It could be through an opponent or into a direction in air.

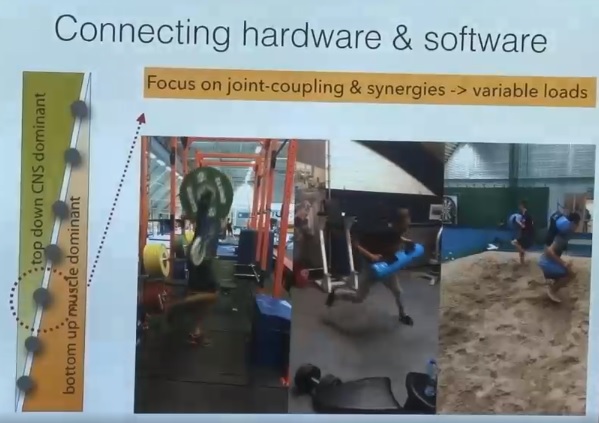

With that comes eccentric strength variables, obviously you have to be strong enough and have ability to exert force into the ground at the proper angles at the proper time. There is a sequencing component, so now a neuromuscular component. What is your efficiency patterning, do you understand how to control your body weight in multiple angles?

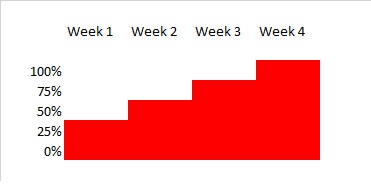

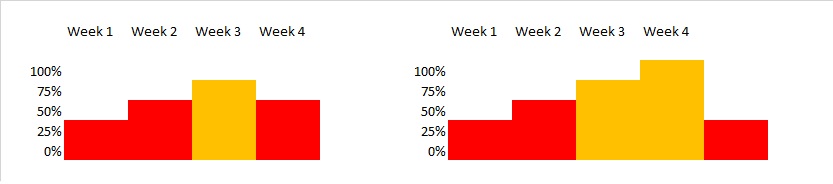

We are looking at your ability to control loads eccentrically. there is tempo training you can do, but also at the opposite end of the Force-Velocity curve you have to be able to control weight and load (using your own bodyweight or an implement such as the Keiser power squat – and rapid eccentric braking.

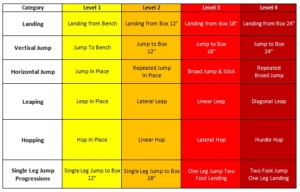

In our off-season we start very, very basic. We start very simple with controlling your own bodyweight so we’re going back to wall drills so we can start statically (load you isometrically), then we progress it to plyometric progressions where we are jumping but we’re also locking in and efficiently loading (eccentric movements) and then recovering force (progressing to ballistics) so for us it’s sticking landings with multi-directional force, unilateral landings, how do you land on 1 limb, how do you land on 2 limbs etc? So that’s a lot of the ballistic eccentrics we do.”

Mark Jamison:

“From a plyometric standpoint we will work through lower level elasticity, reactive strength and then higher shock type work. You have to get into what those change of direction angles look like, and more unilateral plyometric type exercises and progress the eccentric load, whether that’s jumping off higher boxes onto a single leg and having to re-direct or add load to those things and those patterns.

What we really utilize quite a bit is our K-box iso-inertial training, we found really high success with that and again you can really mimic with the squat pattern on the K-box the unweighting and braking rate of force development (RFD) on a countermovement jump. We are hitting 120% eccentric peak power on the iso-inertial training compared to the concentric outputs.”

Damian Harper:

”There are certainly some specific eccentric qualities that are needed for deceleration. We highlighted eccentric peak force, eccentric velocity and eccentric braking RFD, so training qualities in the gym that can target those qualities I think are really important. I’m also a big fan of flywheel training as a way to get that eccentric overload and that should be part of the training strategies to increase the ability of the athlete to resist and control the (downwards) movement. The flywheel also has the advantage of being able to load horizontally, if you’ve got the pulley devices you can do some fantastic exercises in the horizontal plane which is really important from a gym perspective, of the combination of horizontal and vertical loading.

Another training intervention that has some nice training applications for deceleration is isometric loading strategies, so I think the isometric yielding or quasi-isometric loading movements can be really powerful for deceleration, particularly for targeting the tendon structures. For deceleration the tendons are really, really important and the connective tissues are that first line of defence so they are really important from a buffering point of view. So you get a similar kind of eccentric loading with some of the isometric yielding exercises if you go for longer duration holds as well, where we can increase an athlete’s yielding capacity to resist that deformation.

As you start to move up in intensity to some of the more neural based interventions you can look at braking isometrics where we can target some of the braking specific positions and we can start to work with fast or explosive isometric actions targeting inter-limb braking positions using overcoming isometrics. I’ve certainly been inspired by some of Alex Natera’s work on running isometrics and trying to flip that and think about how that can apply to braking isometrics.

Eccentric landing control, and some basic landing exercises as well as reactive strength being really important for deceleration because of that pre-tension and that ability to pre-activate the muscles prior to contact with the ground.”

‘‘When it comes to making technical improvements are there any go to exercises that you would recommend that coaches use with their athletes when it comes to developing those technical aspects of deceleration?”

Mark Jamison:

”High frequency, high exposure to it. We keep the high days high and the low days low, but on a low day it is really easy to do a lot of sub-maximal change of direction work. As we are teaching that we will put heart rate monitors on them and make sure we are in that zone that we want to be in from a training and conditioning standpoint, but we will expoae them to all the different cutting patterns, all the different change of direction patterns and every time they only go out about 4 yards and they have to stick every single plant and hold that position.

Then we can coach that position and you are also getting some kind of isometric exposure to that so you can work on some force at zero velocity when you re-accelerate out of that angle and position from a change of direction standpoint.

We have what we call the 4-8-12; where you sprint to 4 yards on to your right leg, backpedal back to zero; sprint to 8 yards plant and stick on your right leg, backpedal to 4, then you go out to 12, plant and stick on your right leg backpedal to eight and then sprint through. We can work through sprint backpedal, shuffle, crossover and sprint.

If you do it really fast and you ask them, “how did that feel? they have no idea.” If you slow it down they are more aware of it. I see it as a motor skill continuum, there is always that subconscious dysfunction, can you make that a conscious dysfunction, can you at least be aware that you are probably not in the best position. Here is what the correct position looks and feels like, and then continually expose them to it.”

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Deceleration actions are high force and high frequency actions

- Acceleration Deceleration Ability (ADA) test is probably the easiest deceleration test to do in a full team setting.

- Motor control and eccentric strength are key components of deceleration ability

- Quasi-isometric yielding isometrics and overcoming isometrics are also good interventions to improve deceleration

- High frequency, high exposure of sub-maximal change of direction work will be beneficial to help improve deceleration.

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about?

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM

=> Follow us on Facebook

=> Follow us on Instagram

=> Follow us on Twitter