This blog is a bit of a change up in my review of the Pacey Performance Podcast as I’ll be doing a ”shorter” form review of three Episodes in one blog.

Episode 414 – Pete Burridge – Debunking 5 myths on speed training and getting team sport athletes FAST

Episode 417 – Phil Scott – Anaerobic speed reserve: Individualising conditioning in team sports

Episode 418 – Nathan Kiely – A critique of the “knees over toes” phenomenon and maximising cross training prescription

Pete Burridge

Background

Pete is First Team Athletic Performance Coach at Bristol Bears and heads up the speed training element of the programme. He recently wrote an article on Sportsmith which detailed a number of myths that surround this area and how we can debunk them.

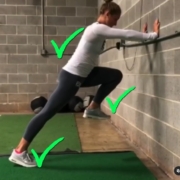

Training video

🔉 Listen to the full episode with Pete here

”Based on your 5 myths around speed training article, one of the first ones you mentioned was that you can’t coach speed. Can you tell me more about that?”

”There is a belief in some circles that if you wanted a fast team you had to go out and recruit speed, that you couldn’t work on it and it was just this innate quality that genetics drove. Don’t get me wrong, there is an element to that but I think that maybe, because that message was so strong some people even now think that you can’t make any meaningful inroads and change on the field when it comes to speed. I’d dispute that. Obviously I’m majorly biased and it is even backed up in research that pretty much once you get to 22 years old, the speed gains really start dwindling in a team sport setting, but from my practiced-based evidence I see you can make change, and it can be long lasting but it takes time, good quality coaching, and a culture around speed from a buy in perspective from the players to actually want to make any sort of change.

The same research has shown that what is called a ”meaningful change” or competitive advantage showed that you only need 30-50 cm of separation, which makes a tonne of sense, because if you’re a footballer and you’re trying to whip in a cross, beating them with a step over and knocking it past them and then being able to find that little yard of space to be able to create a window to whip a ball in, that’s going to lead to success.

In my sport of rugby, being able to accelerate that half a second quicker gets you to a weaker shoulder or at least it means you don’t necessarily go through a hole untouched but it might mean you find a weak shoulder, you might get an arm tackle which allows you to get an arm free which then allows you to off load or find a pass, or at the very least make game line, which is very important.

Actually the effects you need to make are very small. So if someone goes, ”what’s the big deal about making someone’s 10m sprint time go from 1.72 seconds to 1.69 sec?” actually when you extrapolate that out that could be the difference.

”You mentioned also that Technical models are a waste of time for team sports. Can you tell me more about that?”

”When it comes to technical models, I see the argument- why should we conform someone to run exactly how Usain Bolt runs because Usain Bolt is such an outlier we shouldn’t be trying to conform to what he does, because we are all going to be setting us up to fail.

However, there are some key movement hallmarks for successful biomechanical efficiency

One of your guests that you had on recently, Shawn Myszka, I really liked some of his thought processes around self organisation and guided discovery, especially from an Agility perspective. But I sort of see it as being a long a continuum.

Imagine Shawn Myszka on steroids way over to one side where everyone just finds out and discovers it themselves – there is no instruction, there is no guidance – again he would attest that’s not how he coaches, compared to the super hyper track coach where everyone runs how Ben Johnson runs because Charlie Francis said so. We’re at both ends of the spectrum here.

You need to understand where you are with your group. You have to have some sort of end goal where we are aiming to shoot towards something along these lines because otherwise how do you provide any context for how to change someone’s movement if you don’t have a model of what good ”sort of” looks like? In the same way that Stu McMillan says you have got to learn the rules before you break the rules! Absolutely, you’re going to have an athlete that perhaps doesn’t conform to the technical model but can be successful and still run efficiently and fast. But those cases are more rare than everyone so you still need to have some key things that you are trying to get from someone, which will help you as you go along your coaching journey.

You need to reach the messy zone of learning. If you are actually trying to change someone’s mechanics, at first it is going to be messy, you’re not going to get good outcomes but understand that that is part of the process.

The process isn’t going to be linear and if we want to maximise learning we want some element of failure in there

That failure rate can’t be 0% otherwise what we’re tasking the guys to do is too easy. With time and with effort and constantly revisiting what the athlete needs to work on we can hopefully solidify that movement pattern.

- Do it well in a closed setting – an athletic performance lead warm up – coaches aren’t involved, there is not a ball involved, they’re just running in a straight line, not a lot of decision making. Nail it there and once the failure rate disappears to the point where they are able to nail it there, what do you then do? You pressurize it.

- Do it well under competition – race each other in a straight line

- Do it well under a level of complexity – run with a ball or run off line so run an arc, or beat a defender and then run upright into space

- Do it well in a game setting in a 15 vs 15

”You mentioned the process that you would go through to understand whether it was a technical thing or it’s a physical thing Is there anything that you do which gives you more clarity on that?”

”This pre-season we have tried to take our speed programme up a level and taken the concept of ”bucketing guys off,” in part to utilise all our coaching resources as we have a great coaching team, with lots of passionate people about speed. It’s a top down approach that comes from our Head coach – he is invested in it, he sometimes comes and watches the speed sessions, and is interested in the times that the players run and the players know that this is something that the guy who picks the team is interested in.

We get a lot more time than most coaching environments get to work on both generic speed and also specific game speed. When we split the guys to bucket off, it was in part to reduce our coach to player ratio, but it was also to see if we could be a little more specific to the player’s needs. As part of that process we did some profiling, so we tried to marry up some of the more quantitative stuff with some of the more qualitative stuff like video.

We had a couple of categories:

- Any obvious front side issue

- Any obvious shin angle issue

- Any obvious stiffness loss

- Any obvious torso issue – over rotation, chest out, hunched

We used a very simple binary 1 or 0 with the video footage – if the answer was yes to any of the above they got a ‘1’ and we then looked at their RSI scores and ranked that. W wanted to use some of James Wilde hip isometric strength testing but we didn’t get chance to do that. But through some of our gym programming we could kind of tell the guys that really don’t have the hardware to project themselves well. So we were able to group the guys into four main groups:

- Stiffness group – guys with a stiffness issue. You can’t run on flat tyres so our job was to pump their tires a little bit so they get more energy return out of the ground. So they did a little more plyos and reactive SSC based work. It didn’t mean they did no technical work, it just meant in terms of the training pie, more of it was directed towards that. Cues were things like ”pop off the ground,” and ”push don’t smush.”

- Physical group – if you’ve got a 1 Litre engine versus a 5 Litre engine, all other things being equal, the 5 litre engine is going to run past you. So those guys were spending a little more time doing resisted speed work that was force driven in exercise selection. Cues were things like ”tear the ground away, push the floor back, take off like a fighter jet!”

- Technical group – guys with obvious technical deficiencies and may have done more drill based work to really nail the context of running with good postures because you have to have the position and the posture before you can add the power. They might have the hardware, they might have the 5 litre engine, they might have their tyres pumped up, by the driver is an absolute clown. If you put me in a Formula 1 car, I’m going to crash the car!

- Remedial group – lower impact work while still trying to get some of the cues and getting the basics of some of our philosophy across to them. Guys who can’t handle the amount of SSC load, or new players or Academy players who we weren’t fully aware of their training load or how much exposure they have previously had to speed training.

”It’s too risky to train speed. Is that something that you still come across?”

”I think so. My instant answer to that is I’d almost argue it’s just as risky to not train it!

If you’re getting max velocity exposures in your training session then doing it in a standalone session, is that necessary? Probably not.

But if our game demands are very different to our practice demands then there needs to be something done to bridge that gap. If in training you are getting nowhere close to maximum velocity but yet in their games they are getting exposure to it, then that’s a risky game to play. Because we have been smart with our exposure of speed to our guys and risk management from a medical and athletic performance perspective, we have been able to spot a car crash before it happens and hopefully mitigate some of those risks. I believe players need exposure to top end speed whether that is to speak to the coaches and constrain a session so we can get it in the rugby session (which is the ideal) – that invisible thread of training, where you are that guiding hand where they are getting it in a (large) small sided game. But if you are not able to do that then there probably is a place for some stand alone artificial velocity exposure whether that’s in the speed session or within the session itself – it doesn’t really matter as long as you have built up towards it.

Sweet spot for speed might be 6-10 exposures above 95% max velocity per week

- Training– >90% max velocity for over 1 sec – 1-2 artificial exposures per week, where that is either in a speed session or at the end of a warm-up where they do a rolling effort. Backs might pick up 2 more.

- Game – varied. Forwards 1- Backs 2-4.

- Pre-season – week 1 >85%; week 2 85-90%; week 3 90-95%; week 4 95% and above; week 5 light the turbos and run a PB. Do a above 80% warm up, then do a rolling effort and that’s it – you’ve given them what they need.

Phil Scott

Background

Phil is Men’s Strength and Conditioning Coach for England Cricket. Phil comes on the podcast to discuss why he turned to the anaerobic speed reserve to enable him to better individualise aerobic training

🔉 Listen to the full episode with Phil here

”A lot of people might think it’s just a lot of guys standing around. Dispel a few myths when it comes to cricket game demands?”

”It’s deceptive. Fundamentally we have got three formats.

- T20 – really short format

- One day – lasts 7-8 hours

- Test match – lasts up to 5 days

What these guys do is quite phenomenal. Until I got hold of the GPS systems to profile and understand what they did, they, even the players themselves didn’t believe what they did!

T20 – it’s about an 90 minutes of batting and fielding at a time, 3 hours in total. The bowlers will cover up to about 8 km in that hour and a half. If are then going on to bat as well and you are successful, you might run between 1 and 3 km depending on how much running you are doing between the wickets.

They are doing up to 300 metres of high-intensity sprinting and there will be around 100 max accels/decels within that game so it is a lot to take on. Bear in mind that it is a relatively short tournament for those T20 games; one experience was 8 games in 21 days with 6 flights, so a game every 2.5 days if you get to the final, which with that experience we did! Its that ability to sustain that performance and recover from that performance, plus, throw in a bit of jet lag so the guys work hard even for that T20 scenario.

One day – they go on a bit longer but it’s a similar intensity so you’re looking up to 16 km per game for the bowlers and if the batters are going to go on and score a hundred in their innings it could be between 5 and 7 km.

Test match – if a bowler is going to bowl 40 overs in a match we have worked out it is around 50 km for an average total distance for that 5 day match. The highest we have seen this year was 67 km covered in a match over 4.5 days.

I also like to highlight that they usually have a couple of training days leading into that so have 7 km in addition- so they potentially cover up to 65-70 km in a week and they are asked to repeat that seven times throughout the summer, that is a lot of distance and a lot of repeatability purely from a total distance.

The bowlers – Within that 50 km, 7 km of that is above 20 km/h, and 3 km of that is above 25 km/h, and also they stand in a field for around 17 hours

So to translate that into layman’s terms, go for a walk with the dog for 6 hours in a day and every 3 minutes I want you to do a 20 m sprint – that’s the layman’s translation of what they fundamentally do for these test matches. Once we were able to explain that to the players, and the science & medicine staff as well, wow – this is what we are dealing with – can we raise the game and the expectations and the conditioning to cope with that – so it was a bit change at that point!

”Talk to us about the use of Anaerobic Speed Reserve with Cricket”

”If you are going to work above your maximum aerobic speed (MAS) then if you don’t take into consideration their maximum sprint speed (MSS) then some athletes will have more efficiency and more in the tank left to work with than others. So if we take an example:

Athlete A vs Athlete B – Athlete A and B has an MAS of 18 km/h. But they have different MSS. While Athlete A has an MSS of 29 kph, leaving 11 kph “in reserve,” Athlete B has a MSS of 33 kph, leaving 15 kph in reserve. If we programme for them at 140% of that MAS that comes out at 23.8 km/h- which is 53% of the ASR of Athlete A and 39% of the ASR of Athlete B. Athlete A will, therefore, reach fatigue more quickly, and likely will be unable to complete the session at the same level as Athlete B

Athlete A – ASR – 11 km/h vs. Athlete B – ASR – 15 km/h

To take in the MSS if we programme at 40% of their Anaerobic speed reserve (ASR). Athlete A will be going at 22.4 km/h and Athlete B will be going at 24 km/h – that’s fundamentally a big difference, and that for me, was why some guys were blowing up and going ”I can’t complete it”, whereas the other guys were going, ”this is too easy!” [Daz comment: the athlete working at a higher percentage of their ASR will fatigue more quickly]

In cricket we use a 2 km time trial to assess MAS. We do a 40m sprint for MSS with splits at 5, 10, 20, 25, 30, 35 and 40 metres. 90% of my guys will be hitting their MSS between 20-25, or 25-30 metres.

The accuracy of data collection is vital. When collecting maximum sprint speed via timing gates, coaches need to set the gates at a distance that allows your athletes to reach top speed, while also having a small enough margin for the reading to be valid.

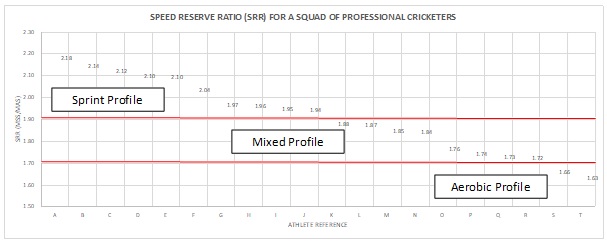

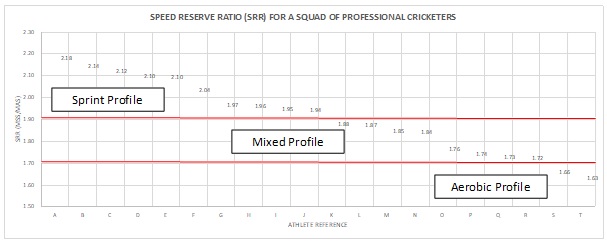

SRR = MSS (kph) / MAS (kph)

Calculating this ratio for your athlete or squad lets you start profiling them and then adjusting your training program accordingly. This is not fundamentally a scientifically rigorous process that gives you an exact figure or fibre type percentage that then dictates the perfect program. Instead, it’s a very good guide for your programs to get the best adaptations for the athletes you are working with.

16.2 km/h was the average MAS when I first starting working in cricket. Initially I was working at above 1.80 as the speedsters and below 1.70 as the aerobic guys. In between that, that is what I was referring to as the mixed profile.

Why is this important? If I take a typical protocol I was using for aerobic endurance development in pre-season and let’s say it was 1 minute on: 30 seconds off (deliberately a 2:1 ratio) those aerobic guys, it didn’t touch the sides, it wasn’t enough and you would hear them say, ”can I do some more?” and the sprinters would start okay, but then they really would blow up, and some of them would not be able to complete that session.

A power output drop off in research I’ve read was 60% on three repeated Wingates where the slow twitch guys was only 40%. In terms of recovery, the slow twitch guys were recovered after 20 minutes, the fast twitch guys were not recovered even 5 hours later.

”How do you actually programme for these groups?”

”If I start with the aerobic guys, they fundamentally need longer to give them time to get into that time at VO2 max- 90% maximum heart rate (MHR) – what I call the red zone. Minimum of 2 minutes and usually up around 4 minutes.

I usually always work with a 2:1 ratio to keep them in the red zone. The intervals for this group can be longer since they seem to take longer to exceed 90% maximum heart rate.

I have previously used 1 km ladders. If you think these guys are going at 17 km/h – which is a 3:30 minute 1 km. So, I found my aerobic guys really enjoyed them and I start them off relatively slowly. So if they are doing a 1km in 3:30 minutes I might start them off at 4:00 minutes or 3:50 min pace for 1km, and then take 10 seconds off for each ladder, and we would up to 5km. They are very cocky at the beginning but that accumulation and build up allows them time to get into their red zone and then hold on to it.

For the sprinters I have found that they can even adapt aerobically to a sprint session as it is such work for them but fundamentally a sprint session with 10, 20, 30 or 40m sprints with a jog back and then go again and try to hold them at 90% of their MSS.

As an example of our approach to training these athletes within cricket:

- Sprint work: experimenting with the rest period can also tap into some aerobic adaptations;

- Sprint endurance training: longer sprints (30 sec) at 85-95% MSS with long rest ~(4-8 minutes);

- Repeated sprints: <10 sec sprint with <60 sec recovery;

- Aerobic tempos: 100m in 15-16 sec, followed by active recovery back to the start in 44-45 seconds.

One of my go to is what I call aerobic tempos and go on the minute. Cricket love ‘6’s’ because you bowl 6 bowls in an over, so I generally break that up into 6 reps and give them a couple of minutes in between. Sprinters prefer that and they’d rather get their time at VO2 max in that setting that even close to a 1 km ladder – that just doesn’t work.

As far as the hybrid group goes – perhaps a bit of a cop out answer – but you’ve got options. You’ve got all of those options above but I perhaps don’t go to the extremes. So I wouldn’t necessarily jump to a 1 km ladder, it might be more of a 500 metre ladder. They also respond well to the repeat sprint programming.

I don’t have any fast bowlers in the aerobic zone- they all tend to sit in the hybrid and speed group – which makes sense because maybe if you are going to bowl at more than 85 mph you are going to have to have a lot of fast twitch fibres for that, and that doesn’t suit an aerobic orientated person. So they are able to get very aerobically fit but they are mostly in that high/mixed category.

Once we see the guys hitting that minimum aerobic standard (because we are then pushing that MSS) those ratios go up a bit more and and we see more guys going up into that 1.9 and 2.0s ratio for ASR, rather than changing the standards.

Accessing the SRR does not work particularly well if an athlete has not reached a minimum aerobic capacity standard. Athletes should complete the 2 kilometer time trial in under 8 minutes (15 kph MAS) before you see any real benefit in applying these individual approaches. Prior to that level, they just need to do more cardiovascular capacity work. Obviously, in each sport there will be a minimum standard your players will need to achieve, based on your own needs analysis.

- Aerobic group – minimum standard is less than 7:00 mins for the 2 km time trial – so 17 km/h MAS

- Mixed group – minimum standard is less than 7:30 mins for the 2 km time trial – so 16 km/h MAS

- Sprint group – minimum standard is less than 8:00 mins for the 2 km time trial – so 15 km/h MAS

This is what the guys in the different groups need to feel they can do in order to feel in good shape aerobically

Nathan Kiely

Background

Nathan is Speed and Rehab Coach at the Brisbane Broncos, Nathan Kiely.

Nathan recently wrote a piece for Sportsmith on the ”knees over toes” movement which he dives deeper into in this episode. Why has this gained so much momentum, particularly on Instagram and how we can be better at being critical when other things like this come along.

🔉 Listen to the full episode with Nathan here

”Would you mind giving us an overview of what the phenomenon is ”knees over toes?”

”Ultimately knees over toes is just an approach to training your lower body, so on its own I don’t have an issue with it. In fact, I’m a big proponent of things like teaching a young athlete in the gym an Olympic style squat – I want a vertical trunk, I do want you ass to grass, I do want your knees going over your toes, I want deep knee flexion. I want each athlete to have the capacity to do that sort of stuff at different times in your programming.

But what I saw was athletes doing knees over toes stuff that I hadn’t programmed for them, and I’d go over to speak to them and say what’s going on here, why are you doing that? They would tell me they’ve got a sore knee, and they’re doing the stuff the physio has given me but I also saw this stuff on the internet and I thought I’d try it out. So I’d go, ”Cool, let me know how you go with it,” and inevitably 2-3 weeks later they go my knee is killing me, they are so sore, they’ve getting worse, maybe its a time to take a step back from the knees over the toes stuff.

There is definitely a time and place for it but I think we needed to work through the methodology of it and understand it better.”

”There is a lot of push for the split squat as being a foundational exercise for this philosophy of training. How do you feel about that and the transfer to the things we want to happen on the field or court?”

”’There are two prongs to it – there is the rehab setting and you’re talking about people in pain, and the performance setting.

Rehab Setting

There are two pervasive claims that the knees over toes community make:

1. The VMO muscle is really important for reducing knee pain – what they have tried to do is use evidence to support their claim, and I actually bothered to read the papers that they cite, and it doesn’t say what they say it says! So the first paper they quote is from a 2013 paper which found that people with strong VMOs in their cohort had a 75% chance of having knee pain, and people with weak VMOs had an 85% chance of having knee pain. So there is a trend but it is not statistically significant and it’s not definitive evidence. So to say it’s a key muscle and everything is about VMO is probably an over statement. It’s multi-factorial- there’s more to it that.

2. You can preferentially target the VMO – with the knees over toes approach – citing a paper in 2016, and I don’t know what they were thinking when they cited this paper as it’s not what the paper showed at all. The study showed that surface VMO muscle EMG activity was highest at 90 degrees flexion so NOT a deep squat, and it actually drops by 30% when you get to 140 degrees of knee flexion.

Athletic Performance

Knees over toes split squat and the transfer to acceleration

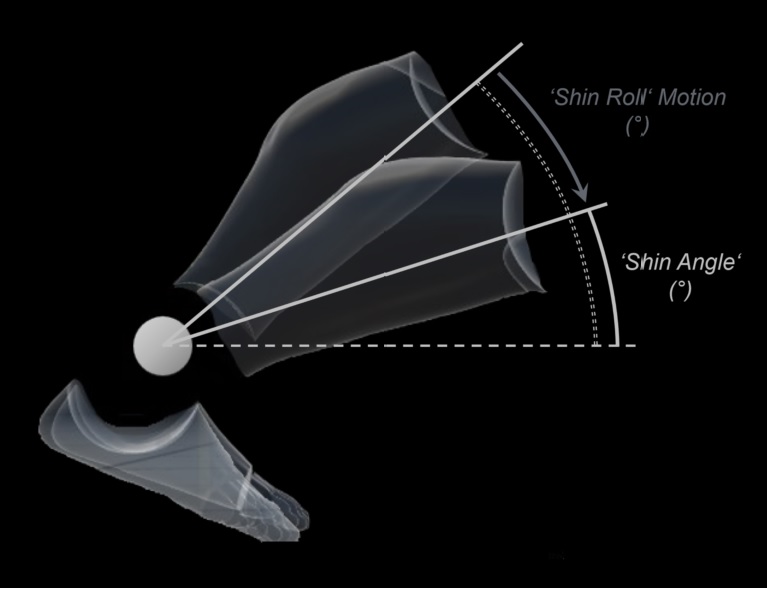

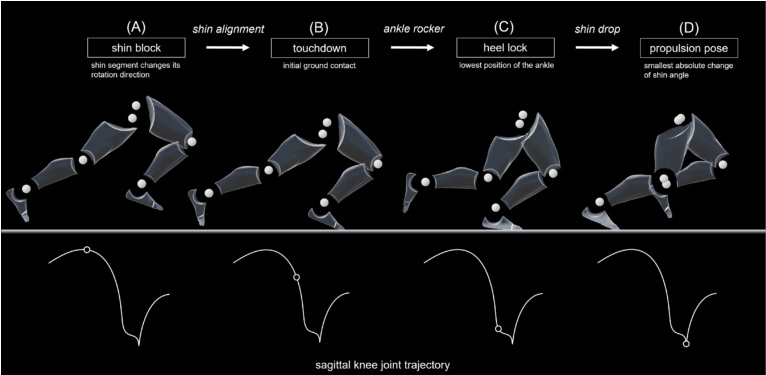

Looking at the shin angle and relationship with knees over toes and making you better at performance. This claim doesn’t come from Ben Patrick.

When I saw that, I thought ”I can see what you’re saying, but that’s not actually how it works. And the reason that’s not how it works is because of the confusion around LOCAL and GLOBAL COORDINATE SYSTEMS. I have to give a lot of credit to Dan Cleather and his book Force, and one of the things he goes through is the confusion around Force Vector theory- which he rubbishes and which comes from the work from Bret Contreras.

Essentially you can look at the individual athlete and the reference frame for them. So you’ve got superior-inferior (up and down) relative to your body and then you have the global coordinate system which is vertical in relation to the World, and your body and the World don’t always necessarily align with each other.

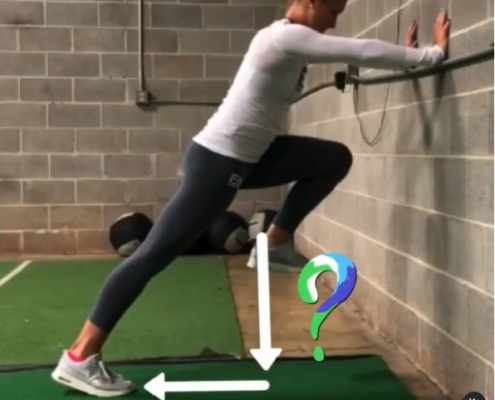

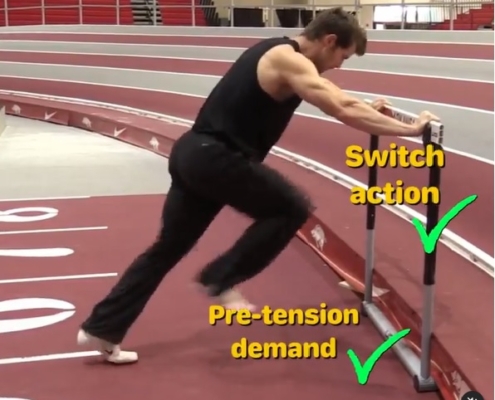

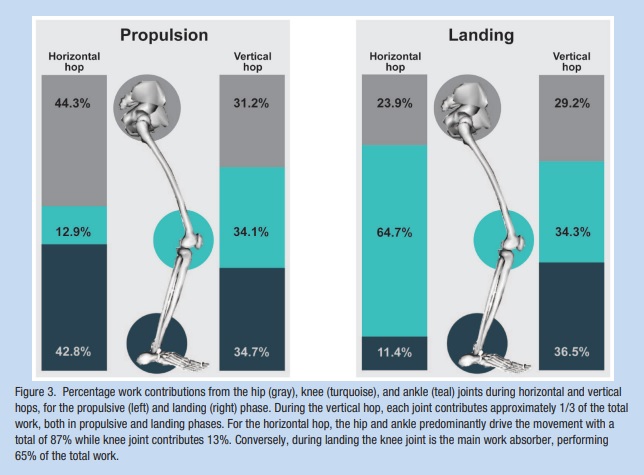

In acceleration an athlete is going to be generating force in an inferior orientation through their body- which is down and back in the World view system and this is where you get confusion around horizontal forces and you look at horizontal GRFs in acceleration and people go, ”oh you need horizontally orinetated strength training like the hip thrust but you’ve got to look at the orientation of the body at a 45 degree horizontal trunk and shin angle. The athlete is stil pushing straight down in relation to the body. Then if you look at that and compare that to the knees over toes split squat, you are distributing load over the toes and pushing up and back through the forefoot to return to the start position, which is a different movement, and it doesn’t correspond neither from a local or global coordinate system perspective.

I would argue that a low box step up has far more dynamic correspondence to acceleration than a knee over toe split squat.

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- It is a misnomer that if you wanted a fast team you had to go out and recruit speed. You can train it.

- Sweet spot for speed might be 6-10 exposures above 95% max velocity per week

- Fast twitch vs Slow twitch – A power output drop off in research I’ve read was 60% on three repeated Wingates where the slow twitch guys was only 40%

- MAS standard – Athletes should complete the 2 kilometer time trial in under 8 minutes (15 kph MAS)

- VMO muscle EMG activity was highest at 90 degrees flexion so NOT a deep squat, and it actually drops by 30% when you get to 140 degrees of knee flexion.

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about?