Pacey Performance Podcast Review – Episode 432

Today I’m reviewing Les Spellman Pacey Performance Podcast.

Just before we get into the blog I just thought it would be pretty cool to point out the timeline of the journey of Les’ growth as a coach, which he mentions in both his first episode with Rob in 2020, but also his more recent appearance in 2023. I didn’t write it in my original blog review as I tend to skip past the bio section. But in this case it’s pretty cool to document it.

He started running NFL combine training camps in 2017 and had 3 athletes, all three did pretty well, next year he had 18 and had pretty good success with them, next year had 28 and started getting first rounders, and then this past year he had a smaller group of 14 but he had the number 1 draft pick and most of his guys drafted and get on teams.

As a side note, he was getting up to over 40 athletes but he has pivoted to running a smaller group of 10 or so athletes in recent combine camps, but is clearly provided a higher level of programming support.

What I loved about his story, was when Les spoke about how he developed his coaching business. When he first moved to San Diego he was sleeping in his car, he needed to make money so he printed out flyers and was putting them on everyone’s cars and hoping someone would call him. But he realised he only needed one athlete, so he got one athlete in and he did his best job with that one athlete. That one athlete led to two more, and he did his best job with those two and just built it. “Honestly, it is was about providing as much value to that one person whoever is in front of me and staying in the moment, that was the most value for me.”

Building the relationship was the most important thing for him.

If you want to hear the first episode (314) you can 🔉 Listen to the full episode here

Episode 432 – Les Spellman – Getting athletes fast when time is limited

Les Spellman

Background

This week on the Pacey Performance Podcast we have Coach and Founder or Spellman Performance, Les Spellman. This is the second time that Les has been on the podcast but lots has changed since then so we wanted to get him back. Les is a speed coach and is best known for his work with athletes preparing for the NFL combine. Because of this we wanted to talk about how to get athletes fast in short periods of time

🔉 Listen to the full episode here

Discussion topics:

”When it comes to the combine and American Football, talk to us about the programme, how you’re putting it together, the amount of athletes and how you’re managing those. I’d love to get a bit of an insight”

”I’ll give some context first. Essentially what happens is guys finish their college football season either late December or early January. We had two guys who played in the National Championship so they didn’t finish until January 9th. When they finish they sign with an agent and then that agent basically pays for their housing, their food, their medical, their training, car, like everything they need until the NFL draft. And then what happens after that agent signs the guy, typically they’ll call me and they’ll say I have a guy that wants to come train with you and then they show up two days later. The process in the past was 20 to 30 different agents in the past calling and that would be a logistical nightmare, whereas this year it is just one (Vaynersports of Gary Vaynerchuk fame). Essentially what happens is once they sign, they come in we go through medical. Most guys are beat up, most guys are coming from a grueling season. Most guys haven’t fully sprint or done anything crazy athletic outside of playing a game because the last couple of games of the season are a grind. You’re tapping into your reservoir of whatever you’ve built in the off-season at that point.

So we go though medical. Once they are cleared – green, yellow, red – green (full), yellow (partial-need some plan B exercises), red (they can’t go on the field). Then we will go through our assessments:

- Force plates – CMJ and Rebound jump with Hawkin dynamics force plate

- Isometric tests – Alex Natera’s ankle, knee and hip iso test

I used to write these crazy programmes before every guy got there but now I have 11 guys so it’s actually relatively easy after that medical, jumps and iso tests to say what are we looking at when it comes to programming. Now I have an idea, I have a shell of what I want to do; how much volume I’m going to push each week, what’s the intensity, what are the fly zones for velocity, how much time am I going to spend on starts, like I know that stuff, but when it comes down to the meat and potatoes of the programme it’s really those first couple of days where we dive in.

”Talk to us about the iso tests and how that informs step 2,3, 4 and 5 in your programme”

“So I just got force plates this year. With the force plates we were able to do the iso test at ankle, knee and hip. The first thing it tells us is which of those three is either under performing, or is becoming more dominant to make up for a weakness somewhere else.

So we are saying, what are some of the running styles that are happening as a result of weaknesses that show up in these tests?

Me coaching six years ago, was like all this technical stuff and me talking a lot, and I burnt out because number one I didn’t have good performances. Five years ago I started to think I’m talking too much so maybe I should just stop talking and I had better performances, so maybe there is something to that. Now looking at it from the physical lens first, what physical bucket may not be filled and how can I identify that? So the iso tests allow me a lens into that. So, we know they run crazy and weird but is it showing up on this test? And if it is, well let’s improve that quality in that athlete, and that’s what it allowed us to do relatively quickly even before we tested them and had them run a 40 Yard sprint, or anything like that.

We don’t test them all at once. It’s in the weight room, so exercise (A1) high pull, exercise (A2) ankle iso test. It was just part of their training. We never made it like we were testing, it was like, hey do this real quick and then push hard. Oh, it wasn’t hard enough. Come back next round and push harder. It just became a part of the training block. We either did it before to potentiate or we did it as part of the training block. The limiting factor is if you have one force plate but having the force plate numbers is massively helpful. I have a metal femur on my left leg. When I did the iso knee test, it was producing 50% less forces than my right side. Now I trained for the past 3 weeks and it’s now down to 25% imbalance. It’s crazy how fast this works.”

”If someone was clearly down on the iso hip for example, how would you attack that just so that listeners can get into your mind with how you look at those numbers and then what comes after?”

“To be honest, we kind of all do the same training with the guys, there’s not much difference; we still have our ankle, knee and hip blocks throughout the week

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday |

| Ankle/Knee | Hip | Individual |

On Saturday we just double up on the weakness, so we will pick one iso on that Saturday as we’re moving fast and we have a lot to do. So if the guys’s poor in the hip, we just hit hip again, if he’s poor in the ankle we just hit the ankle again. We just find the limiting factor and then hit it one more time. That’s the way we’ve seen it work the best because individualising even with 11 guys is tough.

So we have one guy who is super poor on the knee iso and he’s got an imbalance, and when he ran he has poor stiffness; he compresses like a spring, so when he hits the ground his body drops and you literally see the sinking action. So we improved his knee iso by about 8% and his contact times improved, his speeds improved, he is running with a taller hip, so those are the sorts of case studies we are able to capture with the iso tests.

We ended up splitting our speed session into two sessions in a day in Phase 2 (of our three phase programme). Now it sounds crazy but it’s actually not because it’s the same amount of time. So, if I take a 90 minute session. I was like, why was it 90 minutes? It’s because I run my mouth and start talking. When I talk, I interfere and mess things up, and when I mess them up I have to bring them back, so that process takes 30 minutes. So what I started to do was look at my acceleration session, and what is my goal of the acceleration session? I want them to be able to project the body, I want them to be able to switch, hit the ground really hard and aggressively climb in speed. Now, I need them to be able to execute this skill without me, so the first session of the day is an acceleration session that’s basically:

Acceleration Session – physical capacity

- resisted runs – chain sprints, 1080s

- starts – 20Y, 30Y etc

- a couple of timed sprints

- a couple of jumps

- a couple of med ball throws

- and then we’re done 60 minutes

Take a break. We go to the film room. Then I run my mouth. I can talk here. We go through it, everyone takes notes. Here’s the goal we talked about. Here’s where you’re at, here’s what you need to improve. Now after that film session we go back on the field, and on that field session we do a technical session, but the way we do it is we do 30 minute technical session:

Acceleration – technical capacity

- Force, Power or Velocity block

- Force block- some starts – as obviously the start is really important for the 40 Yard dash (combine test)

- Power block – we will do a little bit of starts but we will carry the start out longer, we will do a 7 step acceleration versus a 4 step acceleration, or we’ll do transition stuff working on the torso

- Velocity block

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday |

| Force block | Velocity Block | Power Block | ||||

| Force or Velocity dominant | ||||||

| Technical capacity based around producing forces at the start | It very reactive, it’s all contact time | Think of it as the middle of the run and what qualities you need | ||||

| Banded 1 step repeats | Box switches | Bounding | ||||

| Banded hip sled drives | Reactive hops/pogos | Repeat hops | ||||

| MB throw to start | Drop jump to a hurdle jump | Triple broad jump | ||||

| Intensity might climb moderately but it’s nowhere near as high as what I had them do in the morning | They are qualities that require you to produce power at a moderate GCT. It’s not really reactive like a drop jump to a jump | |||||

Then I’d go over to the weight room and I had much better transfer of the skill than I did if I just had one 90-minute block.

Everyone is the same in Phase 2. We train speed Monday, Thursday and Saturday. But what happens is after phase 2, you’ll have one Force block, one Velocity block and then the power block is either going to be force or velocity dominant. So when you get to Saturday, because you’re also doing individual isos you may have force (basically start or potentiation based work) or you might have velocity potentiation type work. The weight room follows the same trend, we have certain athletes who need to work more on the velocity based power, and there are guys that are still getting stronger working on the force based side when we are in Phase 3.”

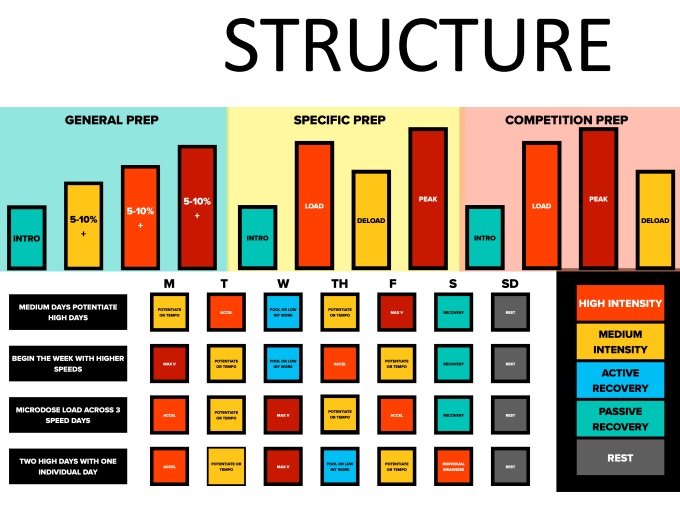

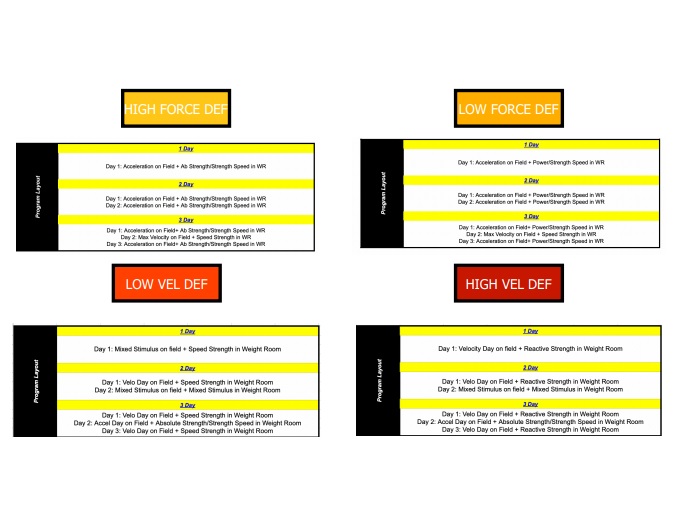

For reference, I’m just sharing below 👇 a slide Les showed in his Sportsmith Speed Conference presentation (which was awesome by the way!). The last option in the slide is closest to what Les is talking about above, but it goes to show that there are options, and several ways to set up your training week.

”You mentioned about the physical work clearing up the technical stuff. Could you give us any examples where you’ve seen that out on the field where that happens?”

“I’d say the biggest one that I usually see get cleaned up relatively quickly is hip extension velocity, so how fast does that hip extend and how powerful, or you could say hip projection. So, most football athletes have poor hip projection in the first couple of steps, meaning that they don’t displace themselves forwards. They like to spin really fast, cycling their legs really fast at the start and they don’t go any where; they take four steps in four yards! When we do the isos, especially the hip iso, or a lunge iso, it cleans it up very quickly and what we’ve noticed is that guys are getting very good projection from cleaning up that physical quality doing the isos or doing some weight room work.

A lot of them have the strength but they’ve never felt that, and being able to get them in that position where they’re producing force a little bit longer than they’re used to has been really helpful.

As for the knee iso, my biggest thing this year has been looking at how much hip negative displacement they have, so does their hip drop in max velocity, and how do I fix that because that’s a huge limiting factor to running extremely high velocities and most football players do not have good stiffness, and really because number 1, they’re wearing 12lb pads all the time, they’re running on soft surfaces, and they will very rarely build up to high, high speeds (versus track you’re running on a hard surface in spikes full effort multiple times a week, you don’t get that in football). So when they come to us, we are putting them in that environment where it’s very fast, very high hip, it’s difficult and the isos help a lot. It allow them to have a higher hip so when they attack the ground, they have less depression of the knee and they can carry a higher hip throughout during the contact phase.

The ankle iso has been huge for us. A lot of the guys tape their ankle in college football so they don’t have very good plantar/dorsi flexion. So when they are getting into positions where they are trying to attack with a stiff ankle they struggle. You see a lot of guys that when they hit the ground their foot and ankle would just collapse. Versus now they’re hitting at a better position and they can manage that isometric so that their ankle is locked as their hip and knee move over it. If your ankle doesn’t have the ability to withstand those forces it is going to drop! Usually Alex Natera’s measurement of 2.6 x bodyweight, if guys can’t produce 2.6 x bodyweight on that test, we are looking at guy’s contact times and seeing that it checks out. As it improved, our contact times improved. Don’t know the science behind it so don’t ask me, but it worked and that’s all I care about when I’m going through it!”

”You will be talking at the sportsmith conference on creating a year round speed system. So when you’ve got an athlete for longer periods of time, what’s your overall philosophy and how do you think about that process?”

“When I got into the private world I never had anybody for more than 6 weeks so it was fun. This is easy, shotgun approach, throw things at them and that stuck, Ok, easy! More recently, I’ve got back into some long term planning working with a couple of schools and I had to come up with a process for identifying what our goals were for the year.

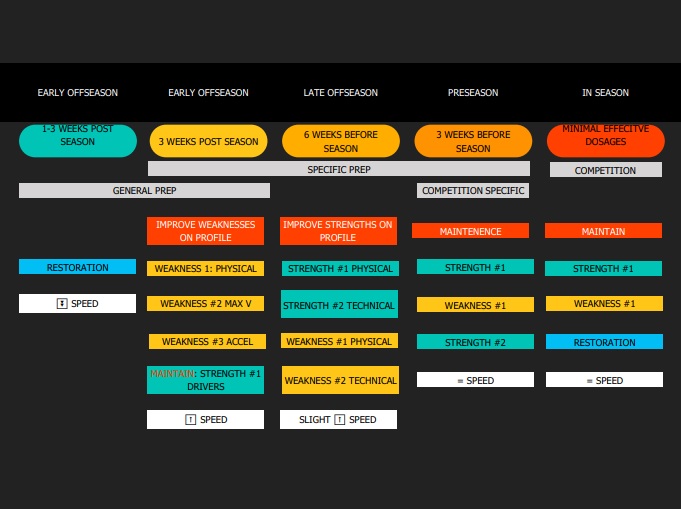

If I was to split the year up, football is very easy, you have in-season, off-season, spring season, pre-season, you have these phases. So if we’re developing speed, at what phase do we want to work with an athlete developing weaknesses versus working strengths? It’s the hardest thing to think about, it’s like if I’m in pre-season do I really want to start attacking this athlete’s weakness? Probably not. But, if I’m in early off-season, do I want to have them just work on their strengths? Well, you can but if I’m trying to make year on year progress thinking of a freshman to senior, how can I make this a multi-year process of developing this athlete?

What I came up with was, what we do is target the weakness in the early part of the off-season, and what we’re trying to identify is both physically and technically what the athlete needs to work on in order to improve. When we get to late off-season we like to do a mix, so there is some of the weaknesses we are improving but we are also bringing in some of the strengths. Whatever they are good at we are allowing them to be good at that. At the end of the off-season and even pre-season we like to maintain some of the work on the weakness but most of it is just keeping them confident, keeping them healthy and really working on their strengths.

With the old periodisation model where you condition in the beginning, then you do strength, and then you do power and then you do speed, so very similar to the linear periodisation model of Charlie Francis, we just keep everything in there at all times but just in different quantities. So when I get in-season, I don’t just abandon the speed training.

👇 Below Les is talking about some of his work with the Arizona Wildcats, which he also presented on at his Sportsmith conference in March 2023.

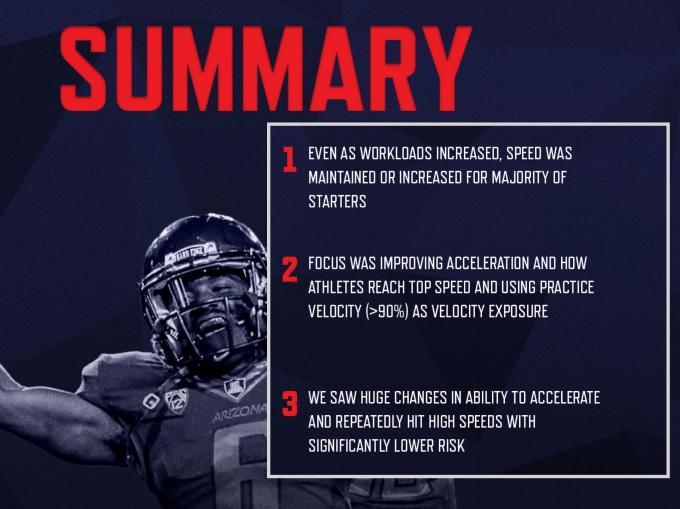

What we were able to do with Arizona this year, was we were able to get 31 new Top Speeds in season, with 35% reduction in games lost and 35% reduction in time lost in season, with no time lost for hamstrings. So looking at the trend, players were continuing to get faster in-season; now they’re not getting faster at the same rate as the early off-season, when they’re working on a weakness and it finally clicks but they are actually faster than they were in the early off-season, which is crazy to think about!

What we noticed is that an athlete’s ability to hit top speed isn’t a quality which is lost over the course of a season. But the athlete’s ability to hit that top speed in the same time frame is lost, which is more of an acceleration based thing.

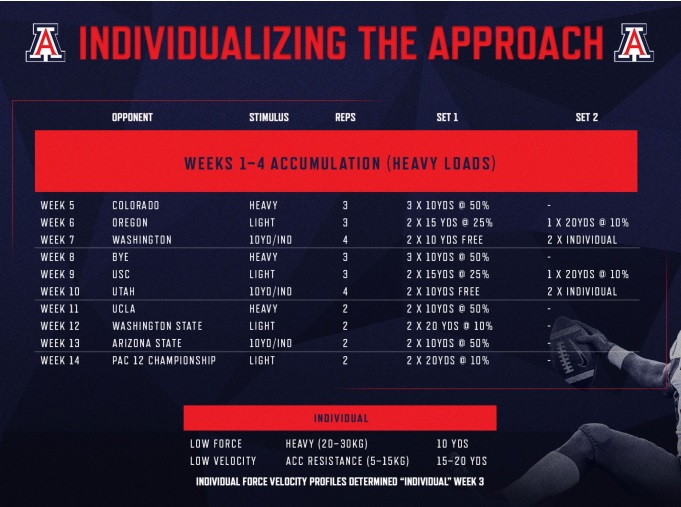

So what we focused on was on maintaining acceleration based qualities, so that ability of that athlete to accelerate to that same speed in the same amount of time throughout the season, and we did that with resisted runs.

You surf the curve and go from heavy to medium to light at different time periods, and then you allow practice to be fast. You allow practice to have the high velocities. A lot of this is the technical sports coaches buying in to ensuring that practices are fast, they are hitting top speeds in games, making sure the guys did the resisted work and the 1080 work and the technical work and all that.

What we realised was that we were getting the peak outputs in games, which is what you want, you want them to play fast. We are creating an environment where players are allowed to play fast, not coming into the game where they are cooked. Most coaches are like, you don’t want to do that [resisted runs] because it might pull back from their velocity qualities (for the game) but we are micro-dosing it – we are only doing 2-4 reps in a session. But just that minimal dosage was allowing the athletes to maintain that ability to be very aggressive on their acceleration and have a lot of power and then practices started to become faster! It became a culture of guys wanting to run fast, and Arizona became a place where guys run fast!

The practices and the system should allow the players to run fast. It shouldn’t just be a volume based approach. There should be adequate rest periods and spacing and make the field big enough, wide enough and reduce the amount of players to allow the players to hit top speed in games. You don’t always have to artificially expose players to top speeds, now you can if they don’t hit it in practices, but what we saw guys were hitting those speeds in practice (95-98% of their top speed) okay, cool, box checked!

Sprinting is the highest central nervous system activity you can do, it’s the highest output for the nervous system, it’s as fast as we can move through sprinting. So it does help the rest of the qualities in your body but you can’t do that without the support of amazing staff (technical, medical, strength & conditioning).

”We all heard about the incredible physical outputs from the USA men’s soccer National team in the World Cup I’d love to get a bit of an insight into the work that you were doing with them in that preparation period?”

“First of all I have got to say that Darcy Norman and Jordan Webb (sport scientist) deserve all the credit because they created an environment that challenged a lot of the norms in soccer.

It’s hard because soccer is a very aerobic culture where they love to do long runs, and timed runs and heart rate zones and it’s a very aggressive aerobic culture world wide. It’s also a sport that is very technical culture, they love practising with the ball, doing everything with the ball. I remember watching soccer teams at college doing conditioning with the ball, and you have a lot of big egos in soccer as well. The bigger the money in the sport, the bigger the egos, go look at the NFL, there are times when you realise sometimes you’re not going to win a conversation. So Darcy and Jordan were able to penetrate that culture and make a massive change by emphasising physical qualities.

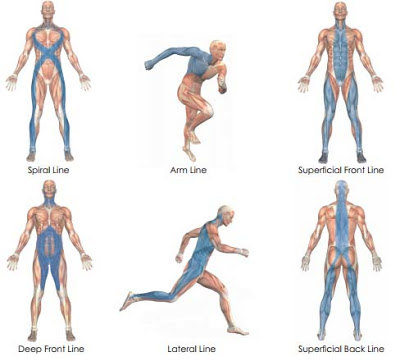

The qualities that we were looking at were the ability to maximally accelerate from a start, but also from a jog or a run and being able to re-accelerate. We looked at max velocity sprinting so a lot of the hamstring type injuries were happening when players were asked to maximally hit a velocity, so how can we mitigate some of that. Also, we looked at deceleration. We did a lot of that. In the game of soccer there are high, high speed decelerations something that Damian Harper talks a lot about. You have a lot of these movements like a 180 degree turn that aren’t necessarily a physical skill or qualities that teams work on! So Darcy is not afraid to challenge that culture.

Everyone got a Force-Velocity profile and everyone got a Load-Velocity profile on the 1080. We were then able to bucket guys into what qualities we wanted to push.

👇 Below is an example that Les gave at the Sportsmith Speed conference on how you could bucket athletes (he wasn’t referring to the USA Men’s National soccer team, But I’ve included it to give you an example).

Everyone knows that soccer guys are not big gym guys. You don’t see them hanging out in LA Fitness doing curls. So we realised that we could get a lot of those force qualities out of heavy resisted running and guys liked it! Because it’s a couple of runs, on the field, you’re in your soccer boots and it’s right after the warm-up and you can get big outputs from the guys and improve their ability to hit high speeds in training!

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Sprinting is the highest central nervous system activity we can do, it’s the highest output for the nervous system

- Benefit of splitting the speed work into two sessions per day – 60 minute physical and 30 minute technical

- Value of Isometric strength testing – to determine which physical buckets could be filled to help fix technical issues

- An athlete’s ability to hit top speed isn’t a quality which is lost over the course of a season. But the athlete’s ability to hit that top speed in the same time frame is lost.

- Resisted runs are easy to get buy in for because it’s simple, effective and easy to implement.

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about?

You may also like from PPP:

Episode 457 Dan Tobin & Dan Grange

Episode 444 Jermaine McCubbine

Episode 442 Damian, Mark & Ted

Episode 381 Alastair McBurnie & Tom Dos’Santos

Episode 380 Alastair McBurnie & Tom Dos’Santos

Episode 372 Jeremy Sheppard & Dana Agar Newman

Episode 217, 51 Derek Evely

Episode 207, 3 Mike Young

Episode 192 Sprint Masterclass

Episode 87 Dan Pfaff

Episode 55 Jonas Dodoo

Episode 15 Carl Valle

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM