Episode 503 – Fearghal Kerin – “Managing T-junction injuries and location based hamstring rehab”

Fearghal Kerin

Background

In this episode of the Pacey Performance Podcast, Fearghal Kerin, Rehabilitation Physiotherapist, Chelsea Football Club, discusses the growing prevalence of T-junction hamstring injuries and the importance of location-specific rehabilitation strategies.

Hamstring injuries are classified into sprint-type and stretch-type, with the T-junction—a confluence of the long and short head of the biceps femoris—being particularly susceptible to injury. This area is complex due to its dual force vectors, dual nerve supply, and bi-articular function, making it challenging to rehabilitate.

🔉 Listen to the full episode here

For a comprehensive overview you might also like to read:

Discussion topics:

“What’s behind the interest in hamstrings. Was it a personal interest? Was it the PhD that sucked you in? Did you manipulate that to fit what you wanted to look at the area you wanted to go down?”

“I’ve had a long time relationship with a professor at University College Dublin, someone who I collaborated with for some time and he came to me 2016-17 with a potential source of funding if we could figure out if I wanted to carry out a PhD, and Leinster Rugby have been amazing for a load of us guys who came through who were all able to complete a PhD through our time at Leinster. So the question was, what would that actually look like? I considered all body parts and initially my thought was let’s go down the concussion route. It is so important for where that sport is going, and if we can make a difference in that area and contribution, it would seem like a very worthy thing to do. But also at the time, like everybody who works in sport, there is the eternal challenge of hamstring injuries in the background and challenges you professionally with re-injuries and the growth of muscle injury classifications and being introduced to that for the first time, and wanting to be able to service the athletes a little bit better. So I made the call, let’s go down the hamstring route.”

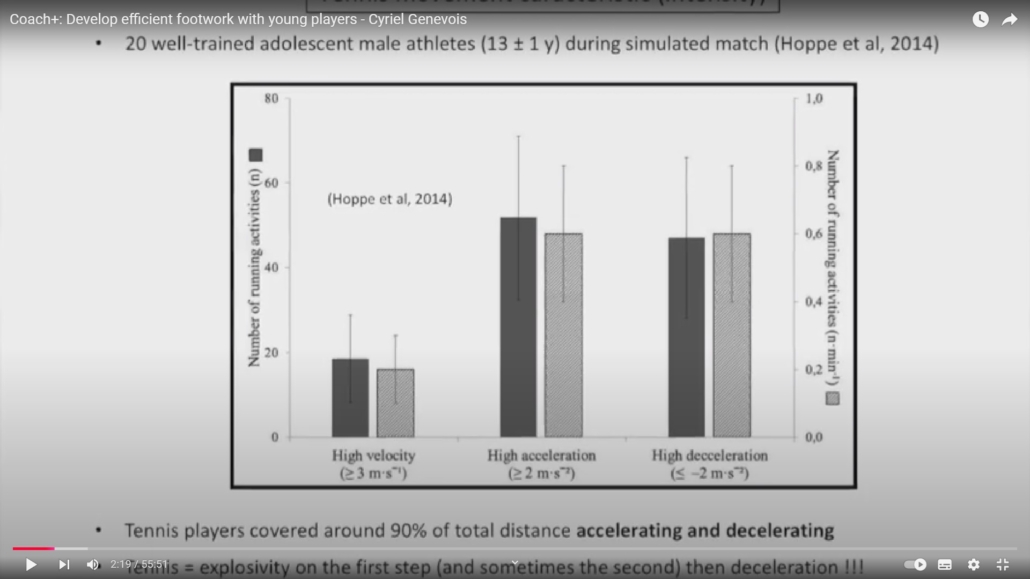

[Daz comment: Side note on on hamstring injury profile:]

Hamstring injuries remain the most frequent muscle injury in elite football, accounting for 34% of all muscle injuries. Even more problematic, they have a high tendency (up to 16%) to re-occur.

- The proximal myotendinous junction is the most injured location in acute hamstring injuries and these injuries generally have a shorter return to play time than injuries affecting the free tendon

- The Bicep Femoris long head has received much research interest as it is the most commonly injured muscle of the hamstring group (more than 80%). It is most frequently injured during sport involving high speed running such as football, AFL, rugby and athletics; injuries occur predominantly in the proximal musculotendinous junction (MTJ)

Key concept:

The most frequently injured of the hamstring muscles is the biceps femoris (BF) in running sports. While these typically occur at the proximal musculotendinous junction (MTJ) Entwisle, Ling has recently descripted the distal MTJ ‘T-Junction’ of the biceps femoris, formed by a complex confluence of the long head and short head in the distal posterior thigh. Injuries to this location have been suggested to be a more severe variant of HSI that should, like intramuscular tendon injuries, be treated as a distinct clinical entity.

Now back to the interview with Fearghal:

“Initially the decision was made we would do a project where we would look at recovery of neuromuscular factors associated with hamstring muscle re-injury:

- Strength

- Fascicle length

- EMG – activation and recovery in hamstring following injury

We couldn’t do this for a couple of reasons. One being change in staffing meaning we couldn’t go down the EMG route the way we had hoped, and probably because of the onset of Covid we weren’t able to pursue the research we wanted to. This meant that it made more sense to pivot a little bit, and I was becoming keener and keener in the area of location specific rehabilitation, and words like T-junction; you’re starting a conversations with people, “how are you managing your T junctions?” I’m seeing these things come up on a MRI scan, and we’re starting to look deeper and deeper into our functional rehabilitation of some of these injuries but are we playing with one hand tied behind our back in terms of the actual pathology and that was a concept that fascinated me because I felt that often we were beating ourselves up in terms of aspects of the rehabilitation, but what I was really interested in was whether we were doing the right things in the first place?

So I pursued that and then we carried out some reasonably large studies looking at our injury data retrospectively and injury location and made some suggestions then through different outputs we had and how that might influence rehabilitation? I guess, once you’ve shown an interest in an area like hamstring injuries where it is so topical, it’s an emotive area for a lot of people in sport where we tend to feel exposed because we care so much and then we get stung with a reinjury. People tend to reach out and then you create a network and a community, it’s a lot information sharing and finding out about how people are doing things globally and I guess I just went deeper and deeper down into that space and ultimately that’s probably what ended up allowing me the opportunity to move into my current role.”

“Briefly, where do you think the interest in the rehab space has come from in terms of education but also general interest from not just physiotherapists but S&C coaches like yourself? I think it’s booming. The interest we get in terms of any sort of rehab content that we put out (even though that’s not the core content) people love, people are lapping it up. S&c coaches often wanting to upskill in that area because they’re put in a situation where they are doing the late stage and maybe their education hasn’t positioned them to feel confident, and they’re looking for other ways. What’s your perspective?”

“I completely agree. I think two things:

- Personality – of the type of people who go into that space – they often tend to be S&C coaches with a massive growth mindset

- Evolution – Because you’re so patient facing all the time you have to demonstrate evolution – you have to demonstrate growth.

I guess people take this all very personally when results don’t go to plan. It’s a fantastic feeling when you get someone back quickly without reinjuring them. But there is no lower feeling than having to restart and go with a second plan to an athlete and explain why it hasn’t gone the way we wanted to and start from zero again, and try and maintain their trust the second time around. So I think people are very, very engaged in trying to evolve their practice and personally I think it is a fascinating area; it’s a real blend of application of some principles around anatomical location and delivering S&C programmes that evolves over time – I often say with some of these injuries it’s just S&C for injured players! This is a really exciting area where we can have some impact with our players, and it’s a major area that is growing and traditionally hasn’t been done that well. S&C coaches tend to drag physios along traditionally and things like sport science, S&C have lead the way for physios and bringing the next iteration of what sports rehabilitation looks like.”

“So latest thinking on hamstring injury mechanisms from the industry as a whole but yours too?”

“I suppose the first concept on hamstring mechanism it based on Askling’s work which defined two main types of injury- binary and 2-Dimensional, but extremely appropriate and that was that we have:

- sprint type injuries – involve high speed running

- stretch type injuries – involve gliding/slide tackle and high kicks

Sprint type work according to Askling’s work will involve the long head of the bicep femoris. Stretch type work will involve the proximal tendon of semimembranosus, with pain near ischial tuberosity and up to buttock.

See full article here for further info:

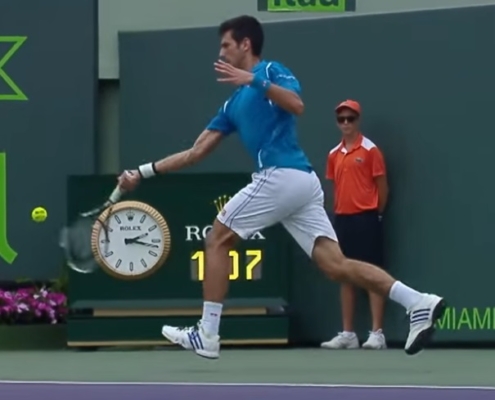

Stretch type injury has an “over-stretching” mechanism so involving hip flexion, knee flexion, trunk flexion type mechanisms. My perception had been that I think we are starting to see less incidence of players sprinting up the wing and pulling up with a sprint type injury. I don’t think that’s necessarily something we see as much. So one of the areas we decided to go down with the PhD was could we describe the actual actions associated with the injury and could we describe the biomechanical position via video analysis. This had been done with a couple of other injury types for position of injury in ankle and ACL type injuries, and adductor injuries so we decided to follow that for hamstring injuries – see the abstract for the article:

– It’s not all about sprinting: mechanisms of acute hamstring strain injuries in professional male rugby union- a systematic visual video analysis – HERE

Results: Seventeen acute hamstring injuries (HSIs) were included in this study. Twelve per cent of the injuries were sustained during training with the remainder sustained during match-play. One HSI occurred due to direct contact to the injured muscle. The remainder were classified as indirect contact (ie, contact to another body region) or non-contact. These HSIs were sustained during five distinct actions – ‘running’ (47%), ‘decelerating’ (18%), ‘kicking’ (6%), during a ‘tackle’ (6%) and ‘rucking’ (18%). The most common biomechanical presentation of the injured limb was characterised by trunk flexion with concomitant active knee extension (76%). Fifty per cent of cases also involved ipsilateral trunk rotation.

Some other research came out by Thomas Gronwald a few months earlier

– Hamstring injury patterns in professional male football (soccer): a systematic video analysis of 52 cases. Abstract link HERE

Results: 52 cases of hamstring injuries were included for specific pattern analysis. The pattern analysis revealed 25 sprint-related (48%) and 27 stretch-related hamstring injuries (52%). All sprint-related hamstring injuries occurred during linear acceleration or high-speed running. Stretch-related hamstring injuries were connected with closed chain movements like braking or stopping with a lunging or landing action and open chain movements like kicking. The kinematic analysis of stretch-related injuries revealed a change of movement involving knee flexion to knee extension and a knee angle of <45° at the assumed injury frame in all open and closed chain movements. Biceps femoris was the most affected muscle (79%) of all included cases.

👆 What they found, which challenged a little bit of what had gone before, unlike what had been found Askling, they found the stretch type mechanism ALSO involved bicep femoris.

So I guess it starts to grow this idea of thinking about the injury mechanism in this 3-D multi-joint, multi-plane mode more than we probably thought about before because when we think of our understanding of kinematics and kinetics, some of that comes from upright treadmill running which isn’t the sport. Many of the Bundesliga injuries involved indirect contact, even some of their sprint type injuries, so thinking probably some kind of contact to the upper body. So, again, while we traditionally think of hamstring injuries occurring in the late swing phase, what’s the contribution of trunk flexion to that? Of excessive hip flexion? Of trunk rotation? So moving beyond a linear running model but also one that is more closely matched to the demands of the sport.

- Acceleration-deceleration-acceleration again

- Curved run

- Duel with an opponent

- Tackling and overreaching

The point that we tried to make with our slightly catchy title, “It’s not all about sprinting,” was to say that not all injuries occur at high speed. We described injuries occurring during kicking, running, deceleration, tackling and in the ruck. Characteristic of those injuries we saw was a combination of:

- Length

- Load

- Speed (rate of loading)

Any combination of those three things can result in hamstring injury. We then published in our supplementary appendix where we also linked the biomechanical position to certain injury locations.

Do we need to think more of a 3-dimensional sport specific multi-directional rehabilitation strategy?

There are probably lessons to be learnt if we are seeing a consistent pattern of injury location associated with a consistent mechanism of injury. That tells us a little about how that tissue was loaded and what positions that might be useful to us or should potentially be avoided during certain phases of the rehabilitation, and also it might help from the diagnostic perspective because certainly at some levels of the sport we don’t always have MRI available to us. There are certain heuristics and rules of thumb, where if you can say to a clinician that with this mechanism we may want to be suspicious of this particular type of injury then that can be very, very helpful too.

“So are you still thinking along the same lines or have you moved on anything based on the experiences you’ve had in different sports and athletes?”

“No. I think we’ve confirmed some key factors. In involving these discussions with others, it’s what people tend to see. A lot of people would share the feeling you don’t tend to see that many sprint type hamstring injuries anymore, as in purely linear sprint type hamstring injuries. They tend to be associated with another action, be that some kind of change of direction or speed, some kind of contact or change of position of the upper body.

Whether that’s because athletes are stronger now than before; the Nordic curl research in football showed that 337 Newtons and being below that with short fascicle length puts you at risk of injury. When we think that most athletes are quite a bit above that now as an average and perhaps we’re no longer having weak athletes that are below that strength threshold, we can now tolerate linear sprinting but now it’s certain other positions that we more likely get an injury associated with different types of mechanisms in slightly stronger athletes. That could be different parts of the muscle, more frequently the intramuscular tendon, or influence different parts of the actual muscle itself so thinking a greater percentage of distal hamstring injuries than would have been described in research 10 years ago, I think we’re starting to see a different profile of hamstring injuries and that’s likely, in my opinion, related to changes in the sport and changes in the athletic profile.”

Distal Bicep Femoris Long Head (A biarticular hamstring muscle)

“T junction and hamstring injuries. Just give us the basics – what is T junction for anyone who is listening and thinking, what is that?”

“I had a familiarity with the Tom Entwisle paper “Distal Musculotendinous T Junction Injuries of the Bicep Femoris” which originally described the anatomy of the T junction and I was aware it was something we were starting to see on MRI reports but hadn’t realised it was probably an area I needed to have a specific approach for. So what is the T junction? It’s the confluence of the long and short head of the bicep femoris.

The bicep femoris, as its name suggests, has two heads – the long head (which is the bi-articular component) and the short head, arising more distally (mono-articular hamstring muscle, meaning it only crosses the knee joint). They form at the T junction because it’s a T shaped structure and it is thought to be an area of the hamstring that is either at particular risk of injury, or will certainly be more complicated when it gets injured because 1) it’s a complex area and doesn’t really fit within any grading or classification structure in terms of the anatomy of the structure itself but also 2) there are duel force vectors and different angles from the long head and short head when they join together. There is also a duel nerve supply with a bi-articular function and lengthening of the long head during hip flexion and knee extension, with the contribution of short head to knee flexion.

Entwisle et al describe the distal musculotendinous T junction (DMTJ) of the biceps femoris where the opposing anterolateral aspect of the long head and the posterolateral aspect of the short head form the musculotendinous junction which appears as a T-shaped structure. They report higher reinjury rates involving this DMTJ of biceps femoris muscle in their cross-sectional study of 106 injuries in Australian Football players. The reinjury rate was 54%, with 86% of subsequent injuries being the same or of higher grade than the index injury.

So with such a high reinjury rate (54%) then the challenge becomes how do you then manage these injuries? Do they need much longer time? Does that mean that they need a specific type of rehabilitation? Does it need an intervention of some sort such as surgery etc?

In our own analysis of injuries [in Rugby], we were able to determine that for us 20% of our hamstring injuries during a 5 year period involved the T junction, and about half of our distal hamstring injuries were T junction injuries. So I would say that if you had a distal hamstring injury, based on our findings in that group and in that sport (rugby), at that time, there is a 50:50 chance your distal hamstring injury may extend within the T junction.

It is suggested that these injuries don’t heal as well and heal as cleanly as other type of hamstring injuries. They settle asymptomatically in 3-4 weeks (and in my experience they settle in 2-4 days). They feel good really, really quickly and you take them up to 70% and everything looks great. Then as soon as you add sport specific demands to your T junction injuries (whether that’s specifically around rotation) or whether that’s acceleration and reaching and trunk flexion (more proximal) and particularly trunk rotation (more distal) for these injury types you then get a second injury, and that’s when things become more challenging. Particularly with your quicker athletes, I think your chances of you getting a good outcome on these I think is traditionally thought to be lower. And some of it is probably because our assessment is limited; what we do on the bed, what we do from a strength diagnostic point of view, we don’t have strong rotational tests and probably due to the nature of the injury having a shearing component these injuries appear to be good really quickly and then they tend to let us down.

Probably what I see and what I talk about is I think there is a very consistent injury mechanism – it’s trunk rotation. I think it’s the ratio of different components of movement that define injury location.

More proximal injuries tend to be more trunk flexion. Distal injuries tend to be more trunk rotation.

Because the distal injury mechanism seems to be related to trunk rotation that probably explains why we can take them through a clinical assessment and they look good, and we can take them through the early stage of rehabilitation and they look good but we’re not actually sufficiently or appropriately shearing the injury location to determine whether it is actually a stable configuration.”

“You mentioned location specific rehab. Would you be able to give us a few examples so people can really get a sense of how that looks in practice?”

“If we are saying that there are different injury sub types then the principle comes from let’s say 30% of hamstring injuries reoccur, so within that, 70% don’t. So the question then is, is there something specific in those 30% that causes them to reoccur? Is it that it’s the intramuscular tendon, the T junction or what exactly is it?

We think most injuries return within 3 weeks but the end stage of muscle healing is 6 weeks and beyond. If we think that certain injury locations are likely to break down then do we give consideration to anatomical healing more so in those cases, and then are there specific actions that should be taken during the rehabilitation process that respects the anatomical healing?

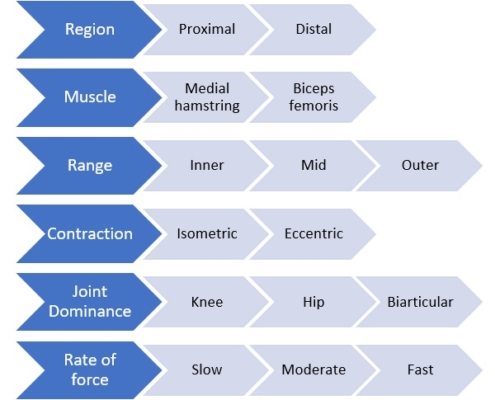

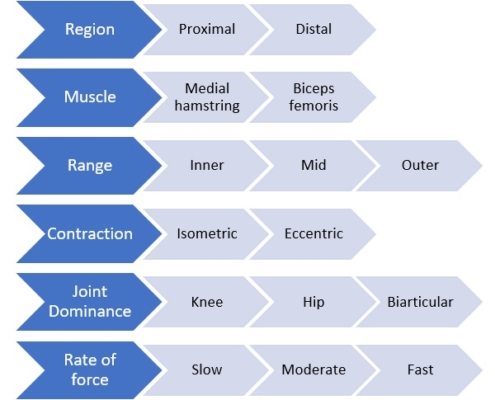

If we take a location specific approach it’s across the entire process, so I’ll split all my rehabilitation considerations into:

The first principle of the British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification (BAMIC) approach of hamstring muscle rehabilitation is to establish an actual structural diagnosis and I think that’s absolutely critical and it certainly underpins location specific approach. Once you’ve determined that you can then set expectations around what is a normal time to return to play for this athlete. We can then start to periodise what we do within that time. We can then reconsider the reinjury risk and then start to think about what are the influences of this on tissue loading, is this is an injury that is going to respond to specific types of loading ie. are we trying to get a specific adaptation within the muscle tendonous junction, within the intramuscular tendon? Can we lean into research from other disciplines, other tendinopathy research and can we learn about heavy slow resistance and how can that be applied to it too?

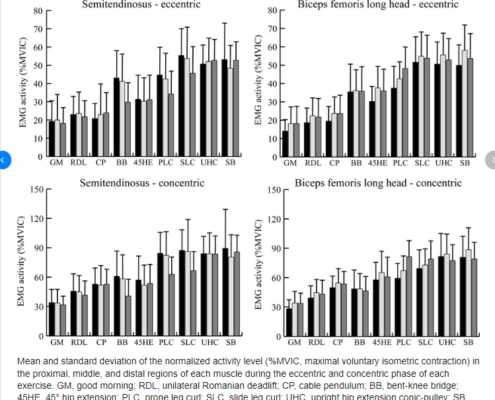

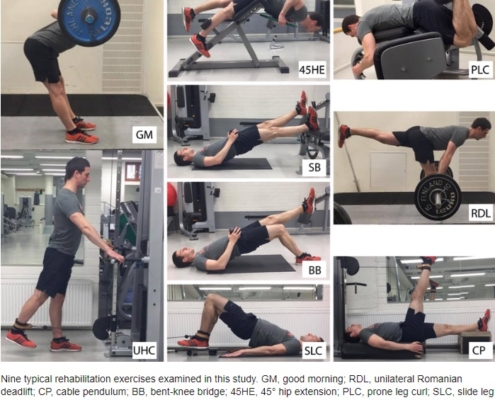

We can also think specific type of injuries that bias particular locations within the muscle, ie. if we know that hip hinge type exercises (research points to 45 degree hip extension exercise, primarily for me I would use the RDL as my main hip hinge exercise) well we know that is going to have the greatest activation of the proximal hamstring. So perhaps if we have a proximal hamstring injury we might delay the hinge type work until later on in the rehab. We might delay outer range eccentric exercises initially because we are trying to respect the anatomy of the injury because we have deemed that to be important.”

[Daz comment: Side note on muscle healing 👇 – from article: WHAT IS A HAMSTRING INJURY?]

As clinicians dealing with hamstring muscle injuries, it is pivotal to understand the basics of muscle healing to optimise our rehabilitation of these injuries. Simultaneously, this knowledge is useful to manage stakeholder expectations and most importantly, the athlete’s risks of (early) return to sport. Most muscle injuries happen at the MTJ. This area is frequently thought of as the weakest link in the chain, because the MTJ is where the projections of the myofibers interface with the connective tissue.

Fibroblasts deposit scar tissue in the gap and as this scar tissue matures, it forms new MTJs with the stumps of the damaged fibres. This maturation is driven by mechanical loading. This is exactly the process where the clinician can provide the most benefit through mechanotherapy. Traditionally, management of acute hamstring injuries (or other acute muscle injuries) included a set amount of days of treatment with (P)RICE, usually combined with passive/active stretching before active loading is commenced. However, there is no strong evidence supporting this approach when managing acute hamstring injuries in the early period. Bleakley et al already suggested a revision of this model called POLICE, adding in Optimal Loading (OL) as a replacement for Rest (R). The aim is to encourage clinicians to think about the optimal progression of rehabilitation and apply an appropriate loading strategy during the first crucial days of rehabilitation. Most likely, relative rest is not ideal as confirmed by recent studies suggesting that an early start with rehabilitation expedites return to sport. Considering the anatomy, physiology and mechanotherapy presented here, we might suggest a basic clinical guideline:

Respect the healing tissue, but start loading early!

Now back to the podcast interview:

“So then we can periodise accordingly if we think that there are specific types of exercises that may overly stress the injury location, perhaps we are going to allow for an initial protective or early loading phase where we will control the:

- contraction type – we might start with isometric in the first instance, and delay eccentric until a certain time point

- length – not overly stressing towards outer range. So if we are doing knee dominant work we will do from inner to mid range

- load – change rep range

- control – delay unanticipated movements and keep the rehab 2-dimensional in the first instance

We can control these factors and layer them in over time. Using RDL as an example we could:

- Range – change to a rack pull

- Load – make it supramaximal for certain parts of the movement or make it light and use it as a movement patterning exercise

- Perturbations – while they are doing an isometric hip hinge hold I can perturb them with a Swissball or they could do bounds ending up in an RDL position, or they could bounce a ball in that position, and even adding in some rotational components to it and some unanticipated movements.

Given that early recurrence is a key feature is this injury, the pace of progression is critical. If attempting to offload the distal BF, exercises that preferentially activate the medial hamstring or proximal BF may be indicated. In addition, initially restricting range of motion and rate of force development, as well as muscle length across the two involved joints are characteristics of exercise selections that can be manipulated and progressed, while still giving consideration to prioritising the adaptations that might be necessary to prevent recurrence.

What environment are we trying to create? Can we create an environment eliminates those signs of re-injury on an MRI through early injury specific rehabilitation that allows for a resolution of the oedema and return of tension by appropriately staging our rehabilitation? So that by the time we actually progress through the rehabilitation we have actually achieved the goals: we have increased their eccentric strength, we have increased the fascicle length and we have prepared them for the game. Can we create an environment where the scan looks good, we have a return of tension and not overly stressed them but they are now ready to progress back into the sport safely. We have ticked off the functional components of the rehabilitation to return to where they were before while also possibly getting the adaptations they needed at the injury location itself.

British Athletics first reported their re-injury rates for C type injuries at around 60% back in 2016, so similar to the T-junction type injuries, on the absolute higher end. For those athletes it is important to note that when we talk about the British Athletics research, we’re talking about really really quick guys so we are not talking about a field sport, a change of direction/reactive team sport. But we are talking about about athletes whose speed is well above 10 m/s and are certainly super elite athletes with re-injury rates of 60%. They described through their approach in Ben McDonald’s paper on hamstring rehabilitation (2019) framework with examples of 2b and c hamstring rehabilitation exercises. I always If you could only read one paper for hamstring rehabilitation injury I would just refer to this paper. It’s an absolute must read, very digestible and has examples of 2b and 2c type rehabilitation type programmes from track & field based sport. It’s a seminal paper for me.

But how can we have our management influenced by muscle injury location to change from 60% to a re-injury rate down to something that more matches some of the other injury locations? They put their money where their mouth is and published their findings after applying this framework and they had dropped from 60% re-occurrence rate down to 0% in C type injuries within a 4 year period!

This is contentious because there is different methodologies across the literature. We can compare their outcomes with other sports but it’s not the same, they are much quicker. For their 2c type injuries they returned in 5 weeks and for their 3c type injuries 7 weeks with successful outcomes. But how do you copy & paste that to field sports?

- Should that field sport athlete take a little bit longer – because once we get them to say 5-7 weeks we now need to add in a sport specific acceleration-deceleration ball work reactive phase?

- Or do we need to take a little bit less time – because the athletes don’t hit the same absolute massive speeds that the track & field athletes do?

So it’s difficult to copy & paste that with any other sports. There is also research carried from Qatar and the group at Aspetar and they showed within their cohort they didn’t see a increase in reinjury and they only see a small difference in time to return to play so they would conclude that intramuscular tendon injuries don’t warrant being defined as a distinct clinical entity. This was a unique study because the researchers and athletes were blinded to the specific injury profile.

We found in our research [from Leinster] that C type (intramuscular) injuries took three times longer than other types of A and B type injuries but you can very justifiably argue that, “well, of course they did because weren’t blinded with the outcomes and you think they take longer, so of course they take longer! We didn’t have higher reoccurrence rates for intramuscular tendon injuries, but we also took three times longer so I guess taking longer you’d want to have lower reoccurence rates than other injury types.

Because of the difference in methodologies, because of the difference in sports we can’t compare across but for what it is worth, my opinion experientially , this injury location warrants being treated differently.

TO BE CONTINUED………

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Hamstring injuries remain the most frequent muscle injury in elite football

- Two main types of injury- binary and 2-Dimensional, but extremely appropriate and that was that we have: sprint type injuries – involve high speed running & stretch type injuries – involve gliding/slide tackle and high kicks

- Limitation in current assessment of injuries – need to think more of a 3-dimensional sport specific multi-directional rehabilitation strategy?

- Injury mechanism – More proximal injuries tend to be more trunk flexion. Distal injuries tend to be more trunk rotation.

- Rehabilitation model – need for more location specific approach. Respect the healing tissue, but start loading early!

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about?

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favuor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM

=> Follow us on Facebook

=> Follow us on Instagram

=> Follow us on Twitter