Todd Ellenbecker- Injury Prevention and Recovery for Tennis

This blog is a review of the Tennis Files Podcast Episode 39 – Injury Prevention and Recovery

Todd Ellenbecker

Background:

Todd Ellenbecker– Todd is the Vice President of Medical Services for the ATP Tour and a Director of Physiotherapy Associates Scottsdale Sports Clinic in Arizona. He is a certified sports clinical specialist, and orthopaedic clinical specialist by the American Physical Therapy Association

Discussion topics:

TE on why Tennis players get injured

”We can sum that up in basically one characteristic word and that is overuse. Most of the injuries we see in the sport of Tennis are overuse. Tennis players typically get injured because they do the same thing repetitively over and over and over again. We call those injuries overuse injuries and they occur simply because of the repetition that is required to get good and develop skill in the sport of Tennis. And then when you play Tennis successfully, playing tournaments, practicing, training and all the other things that go with it you typically because of that overuse become injured.

Even if you have a biomechanically efficient stroke you can still get injured in those muscles, because too much of a good thing sometimes isn’t a good thing, that’s why players don’t play 60-70 Tournaments a year, that’s why people don’t practice 12 hours a day. There are certain limits to our physical capacity, so there is a very fine balance between developing optimum skill and having the optimal amount of recovery so you don’t fall victim to an injury.

Proper mechanics is likely one of the single most important things to prevent injury

Learning the game with proper mechanics, coupled with proper exercise and development of the musculoskeletal system and neurological system etc all those things help to prevent injury as well as proper equipment. All of those multifactorial things can add up into why someone can have an injury.

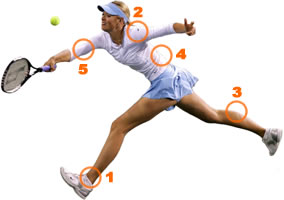

TE on three of the most common injuries seen on the Tour today

”Definitely the number one most common injury is the lower back of the spine. There is so much rotational stress that occurs at the lower back and obviously the kinetic chain is how we develop power in Tennis and so we are always funnelling power from the ground up through the legs, through the trunk (or core if you will) and then to the arm and ultimately the ball.

The trunk is that very vital area that funnels a great deal of rotational power through it and so it is often times subject to injury.

The other area of the area of the shoulder. We see many different types of shoulder injury particularly with the rotator cuff tendons.

The third one is foot and ankle injuries because obviously we have got to get to the ball. Tennis is a multi-directionally strenuous sport where we have to cut and move in multi-directions, with friction on the lower body, friction on the skin and problems with the foot and ankle itself because of the overuse.”

TE on the mindset and approach we should take to protect the shoulder

”Years ago recreational players and even some of the lower level elite players would play tennis to get in shape. So the idea is that people didn’t really do a lot of things to get ready for playing tennis. But now the idea is really that you need to get in shape to play tennis.

So the biggest thing that can be done particularly as it relates to the shoulder, is some level of preventative conditioning. Usually this means things like using therabands to strengthen the shoulder, flexibility exercises particularly something called the cross-arm stretch, or a sleeper stretch; just some gentle stretching and some elastic resistance to strengthen the muscles around the shoulder blade and the rotator cuff are important steps that truly every regular Tennis players should be doing to prevent a shoulder injury.”

TE on some the correct approaches to lifting the weight room and the importance of the smaller muscles

”Most tennis players use too much weight, and do some bench press, some military press and some dips, basically all those exercises work the muscles in the front of the body the pecs, the bigger muscles around the shoulder and unfortunately they are muscles that are already strong in a tennis player. They don’t work the small muscles that hold the scapulae in position.

We’re talking about the four rotator cuff muscles. We’re talking about the trapezius which is a scapular stabiliser. We’re talking about the serratus anterior, the rhomboids, some muscles in the upper back. Those are muscles that to optimally contract you actually use very little amount of weight like the bands or a light weight, and you do it repetitively with a high number of repetitions.

Three times 15-20 repetitions to stimulate the smaller muscles so they not only have strength but they also have endurance.”

TE on the optimal time to do some of these shoulder exercises

”Often times from a well intentioned place they will start doing them right before they play, as this is a good way to warm up using the bands on the court. The problem is, if you fatigue your rotator cuff and then try to go on court and play Tennis for 2 hours or even an hour that’s not really sound. That’s like saying you are going to warm-up 10km before you run your marathon. You’d already be tired and it would impact their ability to run a marathon.

So we really want to make sure we are doing the shoulder preventative exercises for the shoulder after you play or on days that you don’t play.

So ideally you need at least 4-5 hours for the muscles to recover before you play, so you could wake up and do them first thing in the morning if you are not due to practice until midday or later. In a perfect world, do the exercises after you play.”

TE on what type of things tend to cause hip pain in Tennis players

”The key is the very strong link to the core. So probably one of the most significant things about Tennis players who have hip pain is we really want to evaluate their lower back and core musculature. Many times if there is any weakness in their core, typically most individuals will say my core is not as strong as it used to be, especially as we age and become less active.

Sometimes players don’t have enough range of motion in the hip and that’s something we can work on getting more flexible particularly with the two joint muscles as we call them, muscles that cross not only the hip but the knee. Muscles like the IT band, the rectus femoris, the iliopsoas, the hamstrings. When they become tight they can affect the movement patterns and can affect ether the hip or the knee joint as well.”

TE on three things Tennis players can do to prevent injuries

- The number one thing is to learn how to hit the ball properly- develop the strokes

- Make sure that you do preventative type exercises and you get in shape to play Tennis

- Recover after Tennis- try foam rolling

TE on advice to prevent shin splints

”Can happen when you transition from one surface to another, for example grass turf to gym floor. More often than not in a sport of tennis, it’s because of either an inadequate shoe wear and they are not changing them enough or it’s improper footwear. or it’s the actual athletes that are having the shin splints have a lot of pronation or flat flattens, and you get this eccentric lengthening or pull on the muscle that goes up and down the inside of the shin.

One of the first things that we try is to put in an orthotic device and/or change the shoe. If the shoes are very good then we usually try the orthotic.

We also need to make sure the calves are stretched regularly as a tight calf can make you pronate more. We also need to apply ice to reduce some of the acute symptoms of the shin splints.”

Author opinion:

The part of the podcast that was most interesting was the advice to do the shoulder preventative exercises for the shoulder after you play or on days that you don’t play. A common part of the APA pre-tennis warm-up utilises a low volume of single set theraband exercises for 10-15 repetitions.

It will be a good moment to review this approach with the sports medicine team to see if there are anything we might want to do differently in view of this recommendation.

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Overuse Injuries– most of the injuries we see in Tennis are overuse

- Fix your mechanics– proper mechanics is likely one of the single most important things to reduce risk of injury

- Get in shape to play Tennis- don’t play Tennis to get in shape

- Importance of preventative conditioning exercises for the shoulders

- Importance of having a strong core and loose hips

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about? Be sure to visit:

You may also like from Tennis Files Podcast:

Episode 136 Functional Training Principles with Mike Boyle

Episode 134 The Tennis Fitness Mega Episode

Episode 125 Explosive Movement with Dean Hollingworth

Episode 119 Tennis Fitness with Nathan Martin

Episode 101 Dr. Greg Rose- How to Reach Peak Athletic Performance

Episode 82 Dr. Sean Drake- RacquetFit and the Body-Tennis Connection

Episode 79 Injury Prevention with Dave Grant

Episode 78 Strength and Conditioning for Junior Athletes with Aaron Patterson

Episode 69 Strength and Conditioning on the Road with Jonny Fraser

Episode 51 Level Up Your Footwork with Dave Bailey

Episode 33 Mark Kovacs- Strength & Conditioning for Tennis

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM