Pacey Performance Podcast Review – Episode 314

Episode 314 – Les Spellman – Getting athletes fast when time is limited

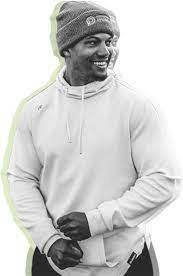

Les Spellman

Background

In this episode of the Pacey Performance Podcast I am speaking to Owner of Spellman Performance, Les Spellman. With the NFL back up and running I thought it would be a perfect time to get a guest on the podcast who prepares these athletes for the coming months.

🔉 Listen to the full episode here

Discussion topics:

”A team sport athlete that has never done speed work before, just give me your general thoughts and give the listener a sense of where your heads at when that athlete turns up to your group?”

”Initially I prefer the athlete that has never done any speed work before, because they have no bias coming into it. When they’re raw I love it, it’s like a raw piece of clay. Our system will teach them the things that they need to learn.

It doesn’t matter if they are a professional athlete or a lower level; the first thing we are going to do is profile the athlete. Sometimes they have these things that we might consider are bad habits or we might say are incorrect, but when we profile them, we see their horizontal forces are amazing, their power and velocity are super high. So, it might be something that if we try to change just because we want them to fit into a certain technical box, we might end up undoing some of those things [that make them great]. One thing I learned from Jonas is just be very cautious about changing too many things at once, especially if it’s something where that athlete is wired that way. Because if we unwire them we better be able to support them, and do everything else we can do to make them take that new neural pathway on.

The main thing we do is profile them, and the second thing we do is build out the technical model. For example, if they are consistently high on their toes, we have vertical drill walking patterns making sure we are cuing things there, and then progressing to see if when they are running does that skill that we are teaching them in a very technical part of the practice, does it translate over to the running? If it does, great; if it doesn’t we keep drilling it until it does (although it may or may not).

I think in the beginning I was coaching because it was a show, and I was trying to get other parents that were watching to send their kids to me so I was coaching everything; it was less about the athlete and more about me at the time, and I was over coaching them. Now, perhaps maybe because I am older (and about to be a Dad) I’m a lot more patient, so I’m looking at number 1, do their physical capabilities line up? If not, okay, here’s the intervention. Number 2, does the technical issue they have, is it going to lead to injury or a decreased performance, and if it’s one of those two things I’m going to intervene. But if their power, velocity and force is high but they don’t look good, well, we’re going to do 1% changes but we are not going to undo the athlete completely.”

”With this team sport athlete that comes in for this speed profile, is there anything else you would do with them as part of that assessment?”

“We really look at three things:

- Force-Velocity Profiling – right now we are doing it off of GPS. We are pulling up their horizontal force number, their theoretical maximal velocity, their ratio of force (max – so where they are at at the beginning, but also mean, over a couple of steps), peak power, and the slope of their force-velocity profile. We are looking at the data for indicators of Low Force- High Velocity (that’s easy – we will add more force and maintain the velocity). Some athletes are High Force-Average Velocity (this is a bit harder to manipulate but we can definitely influence this). We are looking Number #1 at what are the physiological changes we need to make and that’s more on the programming side.

- Split times – the second thing we are going to do is look at their split times. It’s pretty simple, and I think a lot of people look at that first but for us that’s secondary. Are they able to accelerate every 5 yards to 30, or whatever it is we are testing? We are looking for inconsistencies there.

- Kinematics – I want to see ground contact time (GCT), air time, step length. The first thing I’m looking at is their initial acceleration, over the first four steps, but really the first two steps are where we have the largest changes in velocity. I want to see how they manage those first two steps, and then look at top speed, and see if there are imbalances in terms of contact times, left and right, between step length, GCT etc.”

”There is opportunity to individualise but the larger the group the harder it becomes to individualise, so how do you manage that with potentially a quite big spread of experience and movement quality with the sprinters you work with?”

“I think it’s a bit like the weight room. There are things that can be individualised for athletes, and there are things that are just general. We warm up as a group, we will do a couple of high velocity runs without any kind of resistance as a group. But then to get to individualising, we are really talking about individualising each athlete’s peak power, and individualising the load on the sled to identify where their peak power is and assign the % bodyweight on the sled to attack that.

We used to do what everybody did to some extent, where you take an athlete and you do 10% body weight, or you do 40% bodyweight. But it’s essentially like if you went in the weight room, and we say we’re both going to do 50% bodyweight on the bench press, we’re getting two different adaptations because it’s not individual to each athlete’s force-velocity curve.

So one thing about power, most athletes hit peak power within 1-second and are exposed to that peak power for a fraction of a second. So if we’re just going to do bodyweight runs we are just going to expose our athlete’s for a fraction of a second over the course of a session. So our goal is expose our athlete to that range for longer exposure time. So we want to identify what their peak power is and then identify how do we get a sled % body weight to match that? What we are looking right now, is that 50% of their peak velocity is generally the range (Cam Josse said it’s 48-52% and he’s smarter than me so I generally just use the range he works off!).

We do a Force-Velocity Profile – so we do a bodyweight run, a 25% bodyweight run, a 50% bodyweight, a 75% and sometimes a 100% and then we plot that on the chart back to their 50% max velocity, and that’s the weight we put on the sled. It could be 75% body weight, it could be 85%, that’s individual to the athlete! Athletes know that number and we train on that number for two weeks, then generally re-test and give them another number. So they’re pushing their peak power exposure higher and longer and we are doing 4-6 reps for that load per week so that’s the part of their programme that we individualise. And then the rest of the programme is pretty general. It’s not rocket science, I think it’s pretty simple.

With the middle school population we are doing well if we teach them one thing a week that they retain. Yet at first, when I was a less experienced coach I tried to teach they five things in a session, I over-cued and I created paralysis by analysis, Even with the NFL combine I did that in the past. In this past year I try to keep it simple and our philosophy is built around 70% physiological changes we are going to create, and 30% technical. That 30% technical work is around the start and a couple of KPIs such as learning how to switch, learning proper foot contact (reactivity) and that was probably it. With the physiological changes, we are not going to create a tonne of more force, we are not going to take the resultant force from 1000N to 1200N but what we can influence physiologically, is take whatever resultant force they have and change the ratio of force from vertical to horizontal (at the start especially). If we can take that resultant force and make it closer to 50% of ratio of force horizontal, we didn’t necessarily increase their force but we increased the percentage of horizontal to vertical at the start.”

Just before we carry on with the Pacey Performance Podcast Review, just a reminder, if you want to come along to our next Speed & Agility Masterclass with Jonas Dodoo, you can book online below 👇

Now back to the podcast review…….

“Scenario is you have an athlete who comes to you with hamstring issues. What would be the first port of call for you to attack with these guys?”

“This is always a touchy subject because therapists will say, that’s not your lane! It could be multiple things:

- Running volume

- Lumbo-pelvic control (LPC)

- Something physiological – presented on the Force-Velocity profile. For example, we see a lot of guys with super high velocity have very low horizontal force outputs, especially in the beginning. We are noticing in some of our middle school athletes who are velocity orientated, we see these kids complaining about soreness in their wellness scores, they’re more sore and having nagging injuries. So that lead us to ask what is leading them to always getting hurt?

- Something technical – are they extremely backside orientated, are they contacting in front of their centre of mass, how far are they contacting in front? What does their hip height look like?

What we will do number one, is pull back on the velocity side of things. Most of the injuries that they are experiencing are from the higher velocity. We will still keep the velocity in the programme but we will just reduce it, by 50%, and expose them very minimally. What we have seen is that we can make a 10-15% increase in horizontal force within a 4-6 cycle sometimes, especially with our middle school athletes. If we can increase their horizontal power and get them more horizontal on the force side and still keep that velocity in tact, sometimes that tends to work out some of those issues that they might have had at higher velocities because they’re getting to that velocity through an efficient acceleration. If they are not touching on velocity based movements to get to that velocity we will tend to see a little bit less of those soft tissue issues.

All of our athletes will have Lumbo-pelvic control (LPC) exercises that we can work into the programme, and use drilling to practice hip position and keep it as neutral as possible. Sometimes we see that if the psoas and glute can’t work to keep that locked in then we start to see secondary hip flexors come in to play as primary ones, and we see hamstrings and adductors trying to do the job that the glute would do. I try to get the hip to drive the movement and I have Jonas to thank for getting me addicted to doing switching.

I’m not a therapist, I can only speculate. I would never try to work through this on my own. I’d work with other experts and ask them what they see and then try and do my part.

In terms of maximising an athlete’s time, we can’t really move the needle in terms of resultant force or max velocity in a few weeks, but we can also look at things like the time it takes them to get to max velocity. So we might have an athlete who gets to a top speed of 22mph but it takes you 5.5 seconds to get there. For a running back, we can say we want to access that speed sooner for your position. So let’s see if we can get you to that speed at around 4 seconds or somewhere around there. So most athletes we have, we are looking at the horizontal force part of the equation. We can influence in a short amount of time, the ratio of force, so if they are at 45% horizontal to vertical, we want to push it higher. We are not expecting a change in resultant force but if we can do heavy sleds, do drills based around that and increase their power horizontally then it’s going to pay dividends and it’s going to have them run faster.

We’ve seen a couple of guys that had 10-12% increase their [horizontal] force and maintained their velocity, we saw 0.15 to 0.20 difference in their split times over 40 Yards within 4 weeks. We are not really going to move the needle much in terms of velocity, obviously if you have time you can seen athletes get 2-2.5 mph faster which is incredible, but in 6 weeks you can attack acceleration, both early and late acceleration through specific force development training such as heavy sleds, resisted bounds and things like that. And that’s going to move the needle as you’re going to get adaptations to those means.

Also, in season you’ll see athletes that the force decrement over the course of a season is pretty large, you’ll see athletes drop 10-15% over the course of a season while maintaining similar velocities which can expose them to more injury risk. We can help teams track their data on speed without needing to run guys and have velocity based injuries. We can use some innovative ways that look more like special strength than actual sprinting that we can implement into a team environment from professional all the way down to high school athletes.

Just like in the weight room where we try and maintain vertical forces, we are trying to maintain horizontal forces on the field.”

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Assess don’t guess – the importance of the Force-Velocity profile

- Individualisation -we are really talking about individualising each athlete’s peak power, and individualising the load on the sled to identify where their peak power is.

- Horizontal force- the greatest improvements can be expected with 10-15% increase in horizontal power and 0.15-0.2 seconds increases in splits over 40 Yards when you attack the horizontal force component.

- Keep it simple – philosophy is built around 70% physiological changes we are going to create, and 30% technical.

- The KPI for sport is how fast you can reach your max speed – we want to access your speed sooner!

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about?

You may also like from PPP:

Episode 457 Dan Tobin & Dan Grange

Episode 442 Damian, Mark & Ted

Episode 444 Jermaine McCubbine

Episode 380 Alastair McBurnie & Tom Dos’Santos

Episode 372 Jeremy Sheppard & Dana Agar Newman

Episode 217, 51 Derek Evely

Episode 207, 3 Mike Young

Episode 192 Sprint Masterclass

Episode 87 Dan Pfaff

Episode 55 Jonas Dodoo

Episode 15 Carl Valle

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM