Pacey Performance Podcast Review – Episode 456

Episode 456 – Danny Foley – Using a fascia based approach to performance training and rehabilitation

Danny Foley

Background

This week on the Pacey Performance Podcast Rob is speaking to Human Performance Coach at Rude Rock Strength, Danny Foley. Danny is on this episode to discuss all things fascia and a fascia based approach to performance training and rehabilitation.

🔉 Listen to the full episode here

Discussion topics:

”Fascia is a topic that hasn’t been discussed at all never mind in depth on this podcast so I’d like to go there and spend a lot of time there. So before we go any deeper, let’s keep it super simple, and I’m going to ask you what is fascia and why should we be interested in understanding more about it? ”

”The first thing to understand is that the fascial system is real, it’s a palpable tissue and it is essentially a global connective tissue that is highly enriched with sensory bodies, proprioceptors and mechanoreceptors, and it just has a very wide reaching responsibility and functionality.

There is definitely a lot of inconclusive evidence and things that still need to be more conclusively proven from a scientific standpoint, but I think there is a clear reason as to why the literature is lagging and I also feel that there is a lot of intuition that we all understand and just perhaps haven’t put some terminologies to it.

But the fascial tissue specificically really is just collagen, water and has different concentrations throughout the body. So if we take the plantar fascia of the foot or the IT band that is a much more fibrous and dense tissue, whereas if we go to the fascial tissue that is covering the abdominal region that is more of a watery medium, it is much more elastic than it is fibrous. So even though this is one integrated and unified system and tissue throughout the body, there is different densities and concentrations throughout.

The other thing that is interesting with the fascial system is that it has non Newtonian properties so it doesn’t necessarily respond to a stressor or strain in the same way a muscle or other connective tissues like the ligaments or the tendons do.

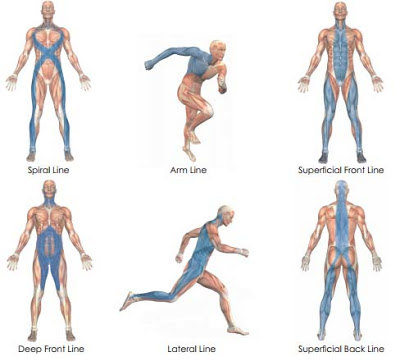

With all of that being said, the biggest priority for the fascial system for the sake of strength & conditioning coaches, physical therapists and athletic trainers is understanding that there is an inextricable link with the fascial system and the musculoskeletal system. So, I think of this like the energy systems, and we understand that we have three primary energy systems that are all working at all times just in different capacities or in fluctuating manners. So the number one thing that I’ll get pressed on with the fascial system is when are we not training fascia? I understand that, but when we are doing a 5km run we are using different proportions of our energy systems as compared to when we are running a 100m sprint.

So if we look at training parameters and the ways we set up and conduct exercise, it works very similarly. There are going to be certain aptitudes that are going to be more predominantly musculoskeletal based, but then there are going to be different layers or parameters where it will be a little more fascial based. I think that is a really important starting point, and from my point of view, nothing about this fascial approach is supplemental to what we have already understood, and on a broad scale, what we are already doing. My interest is deviating at a certain point, once we’ve reached these peaks of strength and once we’ve established the foundations from a physical standpoint, to really try to focus on these integrative aspects of movement as opposed to just continually trying to pursue progressive overload.”

”So when it comes to how you think about programming, and your philosophy, does this way of thinking start from beginners and all the way up, or are you starting to try and understand it when you come to working with more advanced athletes?”

”I definitely think that it is more so for the athletes who are already established and have already developed their rudiments and their foundations. Everything about my work was predicated on injury and pain for a long time, so I’m now in this interesting space where I’m trying to reapply and redevelop some of these approaches, and figure out how much of this is for developmental athletes for the sake of high performance and for people who have low injury histories.

What I’ll say at this moment, is that for pain and injury I think that the fascial approach is definitively better.

I think that on the performance side, it’s a little bit more of the side dish as opposed to the entrée. (Daz comment – Entrée is a French word that Americans use to refer to a “main course.”) Nobody is going to get around developing power, speed, acceleration, developing true levels of strength. But once you hit that point, and that’s another one that is difficult to define – we say, ”how strong is strong enough?” Well is it different for a rugby player and a soccer player? I’d imagine so. However, whatever that context is, whatever that number is for you and your athletes, once we reach that point, I think it goes from pursuing progressive overload to actually deliberately improving the ability to tolerate variability. So, in other words, I want to express those strength and power qualities in as many different ways as I can. I’m going to maintain those fundamental values of strength but then I really want to expose the system to variability more than anything else, because at the end of the day sport is controlled chaos! We cannot continue to sit here and say that American football is a sagital baseball is a frontal plane sport. I think that is very arbitrary. I think there are so many different angles, magnitudes and vectors that we load through and athletes have to respond to, so I think our training needs to mirror that as closely as we can without obviously becoming gimmicky.”

”I think it would be prudent to start around assessing the fascial system and how you go about measuring quality and how much of an impact you can have and where that baseline is. How would you go about that?”

“I’m working on a follow up to Fascia Chronicles with a buddy of mine.

Our goal to be perfectly candid, is to solve this question of how do we know when it’s muscle, how do we know when it’s fascia, how do we know when it’s some combination of each. I wish there was a clear and definitive way of doing this. I wish that there was something that was just tangible, and objective and measurable. We have a couple of ideas that I think are going to shed some light on how we can be a little bit more myopic in how we assess the fascial system. But at the moment, measuring fascia is virtually impossible because it is inextricable. The measurements and assessments that have been done in some clinical settings are just impractical and inaccessible to 99% of us. So what I’ve put together here recently, is I came up with a Fascial Line Assessment Battery.

- Anterior Functional line

- Posterior Functional line

- Lateral Functional line

- Spiral line

These are lines that have associated muscle groups and work in tandem together. So it is a qualittative and subjective analysis but I’m looking at basically the ability to lunge forward to lunge backwards, doing it with more of a coiling pattern, with trunk rotation pattern coming forward and then reaching overhead coming back. Then looking at a lateral to curtsy lunge, and then the third one, looking at a single leg cross-over hinge to a lateral trunk flexion (or side bend). The spiral line looks basically at an upper body rotation with the arms overhead in a split stance.

So this was my way of essentially taking those primary fascial lines, and looking at it as a functional movement evaluation. I’m not interested in scoring it. For me the way that I look at this is that I want to 1) give them the least amount of input as I can, in terms of instructing the movement, I’m going to show them it one or two times and then see how their ability to replicate that is 2) I’m going to really evaluate what I see as compared to what they feel. With the fascial system, one thing that is unique to the fascial system is the concept of interoception – in other words, the sensory bodies that are responsible for detecting how we feel about how we feel. (Daz comment: Interoception is the collection of senses providing information to the organism about the internal state of the body. The process of sensing signals from the body, like heartbeat, breathing, hunger, or the need to go to the toilet.)

By doing the assessment in this manner, where I know what I’m seeing and comparing it to what they are feeling I think that gives me a really good starting ground for trying to close the gap between those two. We see athletes that are all over the place, can’t hold a single leg balance, can’t do a lunge with rotation, and I ask them how do you feel on that, and the athlete says, “I felt great!” So that tells me we are going to have a lot of work to do! And then I’ve got other athletes who come in and move as close to perfect as you can imagine, and I ask them again, “how do you feel on that?” and they’re like “man, my foot was starting to drop when I rotated medially, I felt my left shoulder and my knee come in.” I’m like “OK!” Not only does that give me an idea of how they understand their movement in comparison to what I see or evaluate, but it also gives me a great talking point for how I’m going to instruct and improve these things. I think the ability to develop movement literacy and comprehension is a fundamental responsibility for coaches for sure.

From there, I like to go to anything that anyone would go to for the sake of measuring the tendinous component or the elasticity of the athletes. So I like to do a single leg triple jump or a triple bound. I like to do a single leg drop jump to a vertical, so essentially an RSI. And then I like to do some kind of medicine ball movement. If they are a throwing athlete it will reflect more of that throwing pattern. If they are more like an offensive lineman in football it will be a hip toss. I’m just looking at these things from the point of view of fascial integrity and the ability to produce elasticity.

With the RSI jumps we are looking at the time spent on the ground versus time spent in the air and that to me really is a major separator for programming purposes. For the fascial sake of this, lack of flight time is more indicative of there being a deficiency for elasticity/propulsion. Whereas for someone who is just more heavy footed and doesn’t get off the ground very much then we are going to have a different approach for how we are going to programme against that.

The broadest difference between this conventional and fascial approach is really more so a change in perspective than it is in practice. 80-90% of what I am doing is not different or unique to what any other practitioner is doing, it’s all the same stuff. But the perspective from which I’m evaluating it and implementing strategies for what I’m evaluating is probably slightly different, and that’s why the fascial approach has really shown its value for me.

I’m looking at things from an integrative perspective more so than a isolated approach. If we look at the history of muscle based testing it’s all isolated, e.g., peak isometric force on a single leg extension. My interest is much more on the integration of movement patterns. How do they sequence movement? Now I realise that someone could find it difficult to transition from a forward to reverse lunge simply because they have weak quadriceps. But I’ve seen plenty of athletes who can hold 75-100lb dumbbells in a split squat or rear foot elevated split squat, and when I have them do a anterior to posterior bodyweight lunge they are rocking like they are on a boat and can’t control or coordinate that movement. So that to me is indicative of lacking this integrative capability and goes to that fascial line and ability to produce and reverse the course of movement.

The second thing I would say is that all of these movement evaluations are done barefoot and they are done with a PVC pipe in their hands. So if we think about these lines as being globally integrated and running from the occipital groove coming all the way down to the base of the foot, then for my interests, a fascial based assessment needs to have direct ground contact or interfacing with the ground, and also needs to have something that involves or demands the hands.

Having someone perform a movement where they have to deliberately create tension through the PVC pipe versus doing the same movement with hands on hips often look dramatically different. So if we think especially of throwing athletes or overhead athletes, when we are doing evaluations, we want to make sure that we are integrating that in.

With the foot, that’s really where a lot of my interests start. For me, again, it’s like let’s evaluate what they do in sport and virtually any sport is going to have ground contact and different foot positions (or what I refer to as pressuring) to change the kinematic sequence of the chain.

For athletes who have had a very traditionalist approach to training where it has been very linear and sagittal and isolate dominant, whenever you take them outside of that they just do not navigate it very well.

Just before we carry on with the Pacey Performance Podcast Review, just a reminder, if you want to come along to our next Speed & Agility Masterclass with Jonas Dodoo, you can book online below 👇

Now back to the podcast review…….

”With so much going on and so much detail, how are you taking note of all this, given how subjective it can be, so you can progressively monitor and understand if this person is improving, especially with the integration of questioning such as ,how did that feel? How does this come together into a coherent system?”

“I think the first thing is, I’ve never had the opportunity to work in a University setting for 5-6 years where I would have force plate analysis, and all of these supporting modalities and supporting metrics to help drive my programme. I sure wish I had! So for me, it’s a little more about being resourceful so to speak. But with that being said I think that the number one thing that I try and take away from it is trying to develop and continue to work on the coaching eye, and being really able to analyse movement for what it is, and the best that I’ve ever seen for this is Dan Pfaff. Watching any kind of film analysis with him is really quite intimidating! So I think that the coaching eye that despite the evolution of technology, and all of the resources that are becoming available to us, we can’t lose sight of it. At the end of the day it is a fundamental aptitude for coaches.

A measure that I think is a really good one for the sake of fascial evaluation is looking at time to stabilise. I think that if you take any specific force plate measure, we can have an endless discussion back and forth, about that’s more tendinous or that’s more fascial. Time to stabilise is kind of a unique one because it really isn’t one that is tendon driven, and it’s one that does require motor unit integration and inter/intramuscular coordination and I think that that is something that speaks more directly to the proprioceptive and mechanoreceptive acuity of the fascial tissue as opposed to the muscle belly itself.”

”So we’ve got a training session with this person for the next hour, how are you going to address that with this way of thinking versus a traditional way. Will you just take us through that process?”

“If we start this by just suggesting what is fascial toolkit as a basis for a fascial based training approach? I would very simply say it’s:

- Unilaterally and contra-laterally dominant

- A very minimal amount of bilateral load

- Developed more around the ability to tolerate variability as opposed to pursuing progressive overload

- More open based movements, less constraints, as opposed to more closed chain isolated focus

- Emphasise intrinsic stability as opposed to extrinsic stability

- Look more towards rate of movement as opposed to time under tension

- Omni-directional focus, trying to move in as many directions as possible

There is a time and a place for a muscularly based approach, I’m never going to feel otherwise about that. Also, there is going to be a time and place when we want to be a bit more fascially orientated. I believe that moving in the frontal and transverse plane actually cleans up a lot of the movement in the sagital plane.

If we take the example of the rear foot elevated split squat. This was something that was very prevalent with the military population. You load them up and they move pretty good. When you load them up in one direction, they’re solid 9/10 times. If you unload them and ask them to move in an array of vectors, most of them struggle. When they are on the job, they are under an additional 25-45 lb of external mass at all times, then you have the helmet which is about 7-9 lbs of additional mass. So for this population being out of kit is actually unfamiliar to them. So when we are in a training setting, giving them load is familiar and unloading them is completely unfamiliar.

So with the situation of the loaded split squat looking good and the unloaded version looking bad, the first thing that I want to focus on is mechanical coupling. So I’ll use derivatives of the spring series from Cal Dietz – (check out Danny article Beginners Guide to Training the Foot and Lower Leg).

I’ll use a variation of wall patterns, we will do some sled and locomotive variations that are very lightly loaded and realy teach this concept of intramuscular coordination starting with the foot and lower leg, being able to suspend heel, put the knee over the toe and get force coupling above and below the ankle is critical. Being able to manipulate, move and manage the upper body unloaded so a lot of bridging and crawling patterns, plank push up variations and doing them in a way that is organised to these fascial lines. Really own those positions and be able to integrate.

So with the split squat it’s the same concept. Once we get past that force coupling phase, now I just want to add velocity to it. I’ll actually sometimes just under load them and utilise bands above to help them teach them to be faster in that bottom position. And I think it’s almost entirely a proprioceptive or a neuromuscular aptitude of being able to control speeds at terminal ranges and then integrate them into a different vector rapidly. I think it is a teachable and a trainable quality, and it gets overlooked a lot and we don’t necessarily put the same priority to it.

I believe that moving in more lateral or rotational planes of movement actually cleans up a lot of the movement in the sagital plane. So if we think about what is happening at the pelvis when one leg is extended and one leg is flexed. We have different muscular relationships on each side of the pelvis but then also on the trunk. And then on the leg that is getting loaded we are getting a lot more adductor and abductor when we don’t have load present because now we don’t have something to stabilise against; we have to intrinsically stabilise. In bodyweight we start working the ad and abductor group more and some of the trunk mechanics that are involved there without load I think it goes back to becoming more stable in that sagital plane when we are unloaded.”

”When it comes to pain management what is it about this fascial approach that makes it so effective?”

“The first thing is the amount of proprioceptive bodies that are located in the fascial tissue. There’s been quite a few studies that propose that there are about six times the amount of proprioceptive bodies in fascial tissue as compared to the same surface area of muscular tissue or otherwise. So I think that’s really the foremost priority that the receptors are becoming attuned to how to essentially understand and detect the inputs or the stressors that are being applied and then going from being in a chronic state of pain. A lot of time pain with movement is a sensory malfunction, it’s not necessarily a physical abnormality or deficit, it’s the sensory network. So if we can retrain the body that this position is not bad, then the body can register that and take it on that this position is not painful.

In terms of conditioning the foot I would approach it in the following way:

- Getting out of your shoes and move the foot in barefoot and single leg in static conditions to train the intrinsic foot muscles

- From there I’ll look to more of the rudimentary movements, A series, hop series, skip series, all of those are primary ways that you can load the intrinsic foot muscles.

- The third point is foot compliance or the ability to interface and interact with the ground, in different vectors and directions of force. I want to go back to working in more of that lateral/frontal plane or transition from forwards to backwards, or transitioning from the lateral to medial border of the foot or vice versa.

- The fourth mechanism is going to be the windlass mechanism or the suspended heel so essentially being able to fully mechanically load the plantar arches and being able do so without having a drop in that heel position. I use the spring ankle series from Cal Dietz, and I probably programme that more than anything else, and it’s in almost everyone’s warm-up (Daz comment: The windlass mechanism describes the manner by which the plantar fascia supports the foot during weight- bearing activities and provides information regarding the biomechanical stresses placed on the plantar fascia.)”

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Fascial system is real, it’s a palpable tissue and it is essentially a global connective tissue that is highly enriched with sensory bodies, proprioceptors and mechanoreceptors

- Fascial system has non Newtonian properties so it doesn’t necessarily respond to a stressor or strain in the same way a muscle or other connective tissues like the ligaments or the tendons do.

- The philosophy shifts from pursuing progressive overload to actually deliberately improving the ability to tolerate variability

- The broadest difference between this conventional and fascial approach is really more so a change in perspective than it is in practice.

- A measure that is a really good one for the sake of fascial evaluation is looking at time to stabilise.

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about?

You may also like from PPP:

Episode 457 Dan Tobin & Dan Grange

Episode 444 Jermaine McCubbine

Episode 442 Damian, Mark & Ted

Episode 381 Alastair McBurnie & Tom Dos’Santos

Episode 380 Alastair McBurnie & Tom Dos’Santos

Episode 372 Jeremy Sheppard & Dana Agar Newman

Episode 217, 51 Derek Evely

Episode 207, 3 Mike Young

Episode 192 Sprint Masterclass

Episode 87 Dan Pfaff

Episode 55 Jonas Dodoo

Episode 15 Carl Valle

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM