Episode 446 – Hailu Theodros – Improving change of direction ability, deceleration drills and coaching “transitional movements

Hailu Theodros

Background

This week on the Pacey Performance Podcast is Athletic Development Coach at Speedworks, Hailu Theodros. Hailu spoke recently at the Sportsmith speed conference about gamespeed and his talk was incredible so to get him on the podcast was a complete no brainer.

🔉 Listen to the full episode with Hailu here

Discussion topics:

”When it comes to deceleration and the assessment side, how would you go about assessing an athlete’s deceleration ability and where you need to spend your time?”

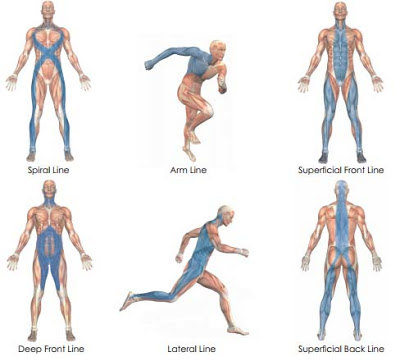

”Generally speaking when developing change of direction ability, the main things I am trying to understand is first and foremost from an applied setting, is what are we trying to prepare for, what are the type of change of directions (COD) occurring in the sport, and what I’m probably referring to more so, is the angles at which these decelerations take place. That’s where my head goes first, but if we are talking more generally about how well an athlete changes direction, the most important thing for me is how well do you brake (and all those KPIs that Damian Harper and others have done a really great job at demystifying, and secondly, how well do you project outside of your base of support.

What I mean by that is how well you brake in a 180 degree turn being the most extreme that you will probably experience from a braking standpoint, having to completely stop your velocity and re-accelerate in the opposite direction, and then those more shallow changes of direction, so 60 degrees and less, and looking how well you step outside of your base of support and re-orientating your trunk to move in a new direction.

I say it is a polarized approach because I think all of the change of direction angles in between those two angles are probably an amalgamation of those two aspects of how well do you brake and how well do you re-orientate your trunk. So if we take a 90 degree cut which is smack bang in between 0 and 180 degrees, there is going to need to be some braking involved, but not needing to come to a complete halt, and there will also be a real need to step outside of your base of support. So if I can understand the extremes and how well you operate in those, I feel I gain a good understanding of how well you will probably execute other angles of change of direction, and obviously there are some physical qualities underpinning those. From an applied setting I would focus on the 180 and the more shallow COD and not test the 90 degree cut, so how well you are able to maintain your speed in the more shallow COD, and the more aggressive change of direction. For me I have found it helpful to understand opposite ends of the spectrum to get a good gauge of your strategies of doing everything else in between.

Testing wise I use the 10-5 for COD and having more of a frontal plane camera. For the more acute angles of COD I’d have a front on facing camera, looking at what happens in the sagittal plane, what does the trunk do, how wide is that touch down distance relative to the centre of mass, and this is obviously being in more of a pre-planned situation.”

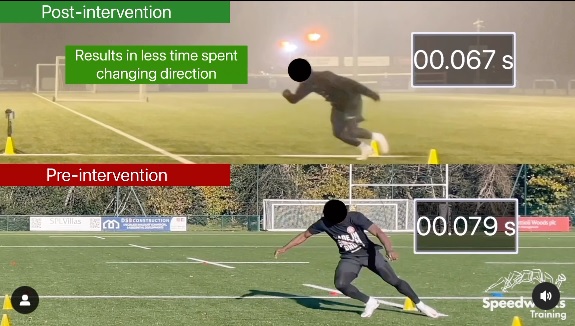

”You put a really interesting post out, and a slowed down video of a 180-degree turn, and you were talking about how much time two comparative athletes were spending in the hole. And that brings me onto my next point which is folding vs. sitting in terms of what the athlete does and looks like in the change of direction. Can you explain that a little bit for us?”

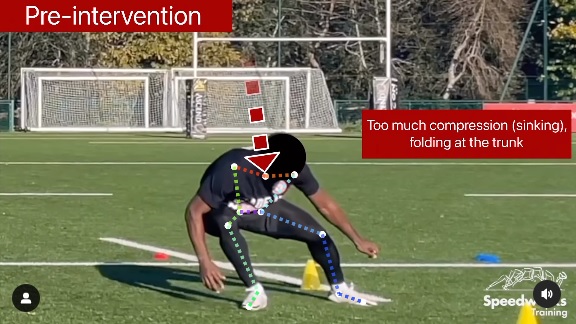

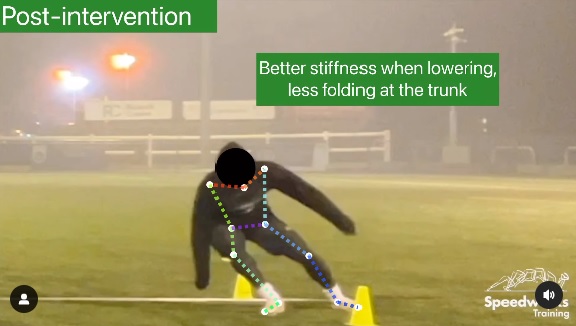

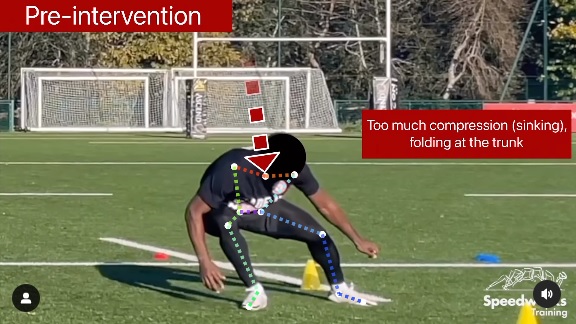

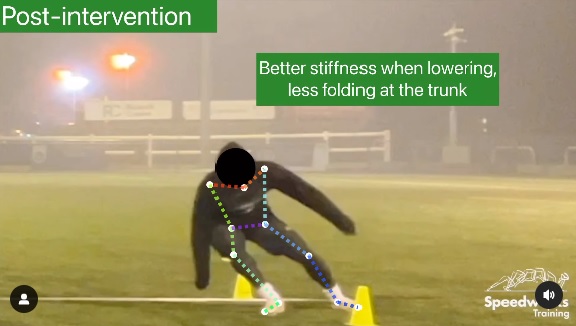

”The post was about some positive change that had taken place over the course of that intervention, and how we were able to improve that individual’s change of direction ability, by focusing on that deceleration more so, and the biggest take away point that came from that was actually helping teach that individual how to fold vs sitting. What I’m talking about when I refer to that, is we know that during change of direction dropping centre of mass (COM) is a key KPI for braking, particularly how (well) does that individual execute the dropping of COM and commonly in the athletes I’ve coached there are those two ways of people doing that. We have a fold, by flexing at trunk, hip, knee and ankle, and I would describe that as crumbling into flexion. Or, are you able to remain fairly vertical and disciplined at the trunk and achieve more of that dropping of COM through predominantly hip, knee and ankle while the trunk remains fairly disciplined? Those are the two buckets I commonly fit people into.

If I go into the relevance of this, sitting allows for COM to be projected down and back and shifting towards that penultimate step, and probably facilitates using that penultimate foot contact a lot more, and from the research that others have done, there is a massive importance for a large amount of that braking to take place at penultimate foot contact, versus actually folding at the trunk and folding forwards to drop COM. This definitely promotes COM to shift forward onto the front (leading) leg and actually doesn’t encourage sitting back and preparing for the new direction, and really create that nice stable base of support and counteract that forward momentum, and putting appropriate braking forces in the right direction.”

‘The importance of the trunk and the orientation of the trunk to decelerate and then re-accelerate is that something that is isolated in terms of a training capacity, or is that something that is a result of something else?”

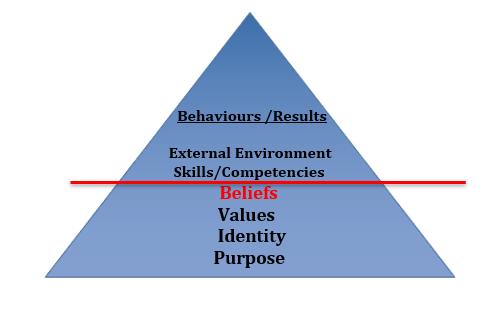

”I don’t want to say it is one or the other, I think it can be an amalgamation of both. It could be that individual’s capacity that is forcing a folding action – maybe they aren’t able to produce the right amount of (eccentric) forces at the lower limb in order to create the right amount of braking and therefore more of the body needs to be involved in that braking action, and counteract that forward momentum. Or, actually that individual doesn’t have the confidence to increase that touch down distance. In coaching deceleration, we feel that deceleration is the inverse of coaching acceleration so in acceleration we see:

- hip height going from low to high

- a decrease in touch down distance to increase our propulsive forces

So when things get confusing, how can I understand it better, and actually the folding action doesn’t support our ability to increase touch down distance, doesn’t support our ability to redirect our COM in the new direction. When we look at sitting, it definitely does support that a lot more, as a result of dropping COM (hip height) effectively whilst increasing touch down distance and actually having a negative displacement across the steps, as opposed to what we see in acceleration which is a positive hip displacement across the steps.”

”Would you be able to take us through what you’re actually looking for when that athlete starts to decelerate, and and then look at some drills to be able to coach them into these positions?”

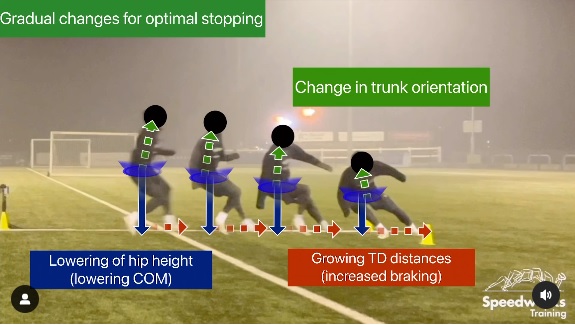

”Going back to some of Damian [Harper’s] work, I’m predominantly looking at the anti-penultimate, penultimate and final foot contact. We start from the anti-penultimate, and we use this phase of projecting back, and is that individual able to increase their touch down distance and have the confidence to increase it, get their foot out in front of them and project themselves backwards in order to counteract the forward momentum that we get from acceleration, or linear speed. And then progressively over those steps, as much as we are projecting backwards, are we also able to drop our COM? The importance of dropping the COM is so that we can apply those braking forces more horizontally in the opposite direction and it’s really, really challenging to stay very vertical and increase touch down distance from an anatomical standpoint. And again, I’ll refer back to acceleration, it’s very hard to project forward when you are in a very upright position.

So across the anti-penultimate and penultimate step are they able to increasingly step in front of their base of support and be fairly upright in their trunk whilst dropping their COM? That can be a little bit tricky to see, but again it is this sitting action, almost sitting on the toilet is a good way to describe it; we wouldn’t flex at our trunk in order to sit on the toilet, we stay fairly vertical. So we are sitting into our hips, dropping into our hips, and when we get close to that final foot contact we are hoping that a large part of our braking has been done in the anti-penultimate and penultimate contact, and the final foot contact is really to create a final block to decrease our forward momentum before helping us to project forward into the new direction. We are looking that in that position the orientation should be of the trunk but also the shin in that final foot contact directing towards the new direction, but also the ranges of motion that that individual goes into should be fairly shallow, on the final foot contact providing that they have done sufficient work in the proceeding steps.

Getting out of the hole and how long you take to get in and out of the hole, and if you spend too long in the hole, it is probably a lot of the time, because you haven’t done enough [braking] in the previous steps and your final foot contact is working extremely hard, not only to brake but also to re-accelerate. I see those preceding steps as helping your final foot contact out. Can we help ourselves out by doing more work in the earlier steps? Final foot contact has a larger emphasis on projecting out into the new direction, than it does slowing momentum down.

Foot positioning

If the foot isn’t beginning to reposition towards the new direction at the penultimate step it is extremely hard to create the right braking forces, to block against forward momentum, when feet are facing forward towards the initial direction we come into. Not only does that rotation of the foot need to happen at the penultimate step to redirect, I also think it needs to create a real block to go against momentum of the initial acceleration direction, so it almost has two roles.

By the time the final foot contact takes place, half of the work [of braking] should be done, if not more of the work should be done, in order to redirect.

There is just a slight change of orientation of the trunk in the transverse plane, but we shouldn’t have to spend more time having to take another step in order to redirect. You commonly see this with players doing a 180 degree COD, they struggle to stay within a corridor of COD, and what I mean by that is that they come in and really curve their re-acceleration, because either they haven’t prepared well enough for the new direction, or, they need to take more steps in order to brake and decelerate their horizontal momentum.”

”When you’re coaching deceleration in this capacity, like we’ve discussed, is this always done in a 180 COD, and would you always do this from a max speed perspective, because often in team sports when you’re making a COD you’re not particularly going fast. If you’re a defender, for example, you’re jogging and then a quick deceleration and COD, so I’m just wondering how you incorporate the demands of the sport and the position with the coaching of it ?”

”For me, I think braking as a quality, that is going to happen at the extremes of the CODs, and if I really want to overload that, I might use that [180 COD] as an intervention. But definitely I agree with you (and especially when we come onto talk about our Speedworks levels) it needs to be more representative of what we are trying to train for. Yes, braking might be your limiting factor, as to why you can’t stay tight in a 1 vs 1, or you struggle to change direction. So I might use a 180 COD to really overload that stimulus, but I definitely need to shift our training along to make it more representative of what we are trying to train for, specific to the velocities and angles of COD that take place, but I don’t necessarily think that it always needs to be a sprint into change of direction.

Some of the ways in which we have coached it. have been based on applying a well understood and applied framework for acceleration so there is going to be some:

- Isolated exercises – that focus on key moments of the penultimate contact or final foot contact, or trunk orientation.

- Integrated drills – exposing the athlete to different CODs, coming in at different speeds, different types of derivatives- which are transitional movements in themselves, such as lateral shuffle, cross-over and backpedals, where there is still an element of braking involved. These allow you to focus on key shapes and positions at lower intensities and lower speeds.

We can also do two to three decelerations from walking and jogging positions that are accentuated from a band, pulling that individual further into the direction they are initially heading in. We can not just decelerate to stop, but decelerate to move off again. We can decelerate off larger distances, shorter distances, there is a real wide spectrum, it’s just important to understand the context of what we are working in, and breaking it down before we build it back up again.

”Before we go any further, would you be able to talk us through the speedworks levels, as I know it is something that was mentioned at the conference a couple of times?”

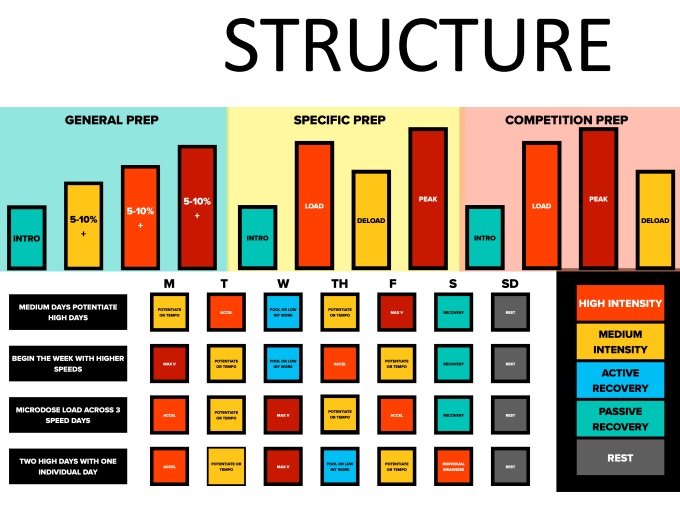

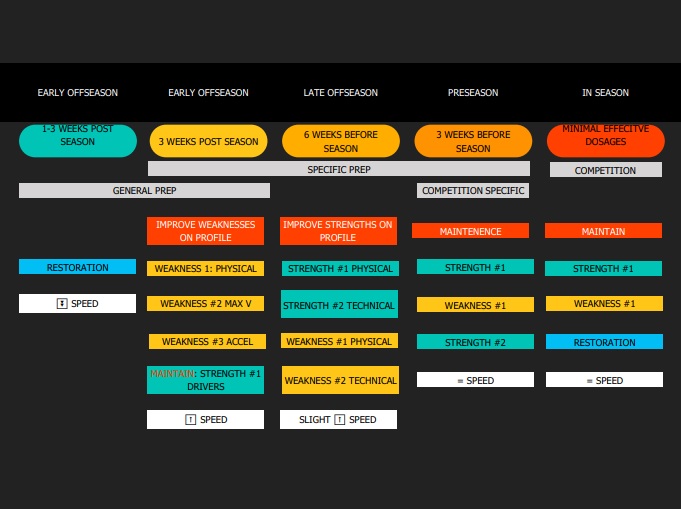

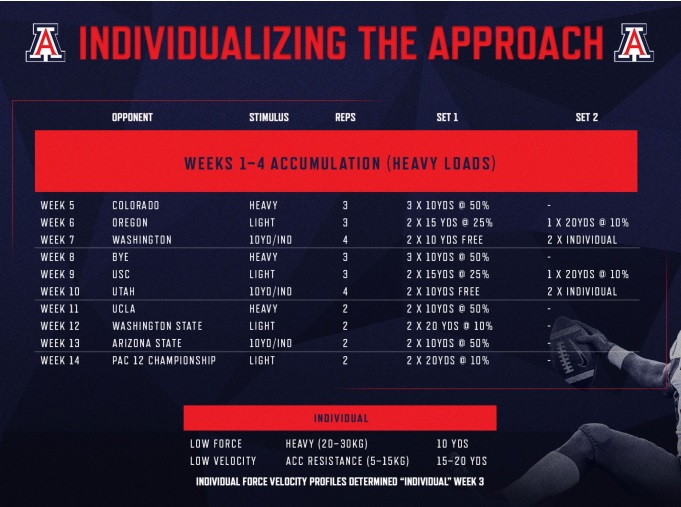

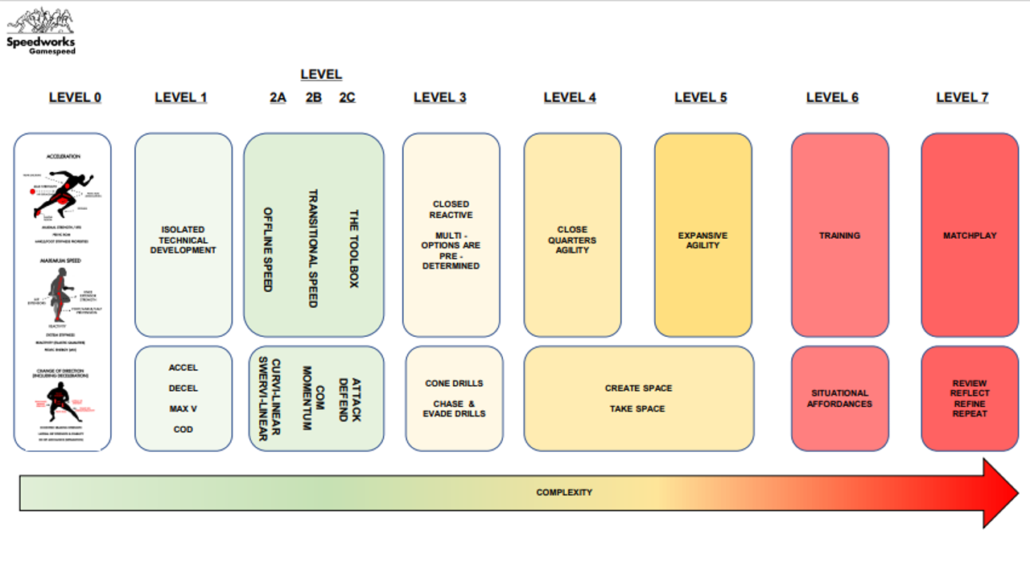

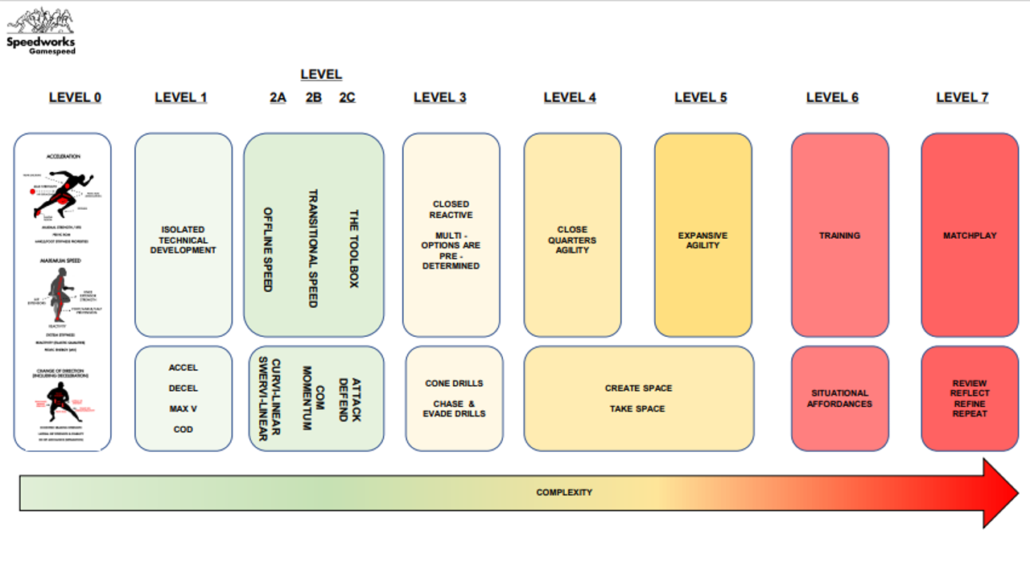

”Specific to this context around deceleration, Gamespeed goes from Level 1 to Level 7 and increases in complexity, and gets closer and closer to what we understand as Gamespeed.

Level 1 is very much about isolated drills and the development of an attribute whether that is acceleration, or deceleration in this context, and the 180 COD provides that real challenging stimulus for braking as we have discussed. Level 1 is a really great place to embed some key concepts, that we need the individual to really understand about braking, such as sitting vs folding, which is going to be a key thing we want that individual to understand in level 1. That will be a continuous theme as we complexify things and make things more reactive (in higher levels), and the challenge is going to be see if that individual can still achieve the fundamentals, with less time at levels 3, 4 and 5.

Then as we move into level 2 it is about adding complexity by adding different variables in, challenging velocity, different directions, different positions, so not just from cone to cone as such. So now it’s not just a 180 COD to a cone where you stop when you reach there, and then come back. It might be applying different angles so you’re doing a zig zag potentially and you’re decelerating to the first cone before decelerating out, or you are starting in different positions before you decelerate, or you are in a specific zone before you decelerate.

When we move into level 3 the practice designs are more representative of the end goal, or what happens in the game, but in a closed setting.

These are the situations, these are the actions that take place, how well can you demonstrate braking when you have plenty of time to focus on it? And again, as we begin to complexify these things a bit more we can make them a bit more reactive as we move through the levels. We can make things a bit more reactive by using me as a coach, and calling different cones/colours, and reduce the time available to prepare.

Levels 4 and 5 are going to be about creating more situations and for me the coaching needs to shift towards more the objectives of the task and the task we are trying to represent from the game, as opposed to what the movement should look like. Ideally yes, the movements (performed well) should equal achieving the task better and be more successful at the task. But I think what gamespeed allows us to do, is appreciate that even though there are core fundamentals there is a large amount of variability that will take place when we spend more time at levels 4 and 5 and things are more reactive, and open. That variability is important because it is more representative of what happens in the game, there is no situation that happens in the game. So how can we artificially create this environment that creates that?

Your objective in that situation was to get tight to your opponent, and you didn’t, and that was probably because you didn’t sit enough or you were folding and you were still in your final foot contact versus shifting towards your penultimate foot contact, and that is why maybe you weren’t as successful at the task.”

”Are there certain types of drills that you could share that you use when you are trying to develop these deceleration qualities that we are speaking about?”

”I think first of all, especially when we are going back to this point of spending too long in the hole, it is important to highlight that it is important to understand what the limiting factor is to spending too long in the hole. Is it a physical restriction? Is it a physical capacity limitation? Or is it more of a movement strategy? Be it that you yield too much or you go into very deep ranges of motion on that final foot contact, and you don’t have those reactive strength qualities to be quick out of the hole. Or is it that your trunk is all over the place, throughout those deceleration steps and your final foot contact? So highlighting ‘it’ first of all is very important, and to understand that there are differences and what is the cause and effect of spending too long in the hole. Once you identify that you can go after it.

Using the original example earlier, that individual’s focus was actually around better trunk orientation in shallower ranges of motion and expressing more reactive strength in that final foot contact. So a lot of the drills that we went to were:

- things that happened out on the pitch– hop & returns – plyometric variations

- things that happened in the gym – focused on overloading the physical elements (which was a smaller portion of the training for this individual), while still integrating a teaching component. So there was a lot more supra-maximal work eccentric, isoinertial flywheel work to really challenge the eccentric rate of force development (RFD). It was highlighted that this was a contributing factor to spending too long in the hole, not being able to create those high forces quick enough, which is probably why the trunk was getting involved.

While in the gym doing that eccentric and isoinertial work, it was 100% reinforcing that message that I need you to sit, not fold, to remain vertical through your trunk, to remain disciplined in your trunk while executing these exercises, sitting through our hips and knees as opposed to through our trunk.

Then we went out to the on field work, which was a larger portion of it, the work was focused around hop & return in the frontal plane (lateral hop & return), but accentuated the eccentric component by using a band to pull that athlete further into flexion, and the athlete has to do his best to resist against this added velocity and accentuated action. We did a lot of lateral shuffles but with the stick overhead to really challenge that individual’s ability to sit and not fold, when doing a repeated shuffle, when reaching those end points. Can you stay in fairly upright positions when moving off each side when moving left and right. Finally, a lot of that work was plyometric work in the frontal plane such as skater jumps, really reinforcing that point of bigger touch down distance, shallower ranges of motion, really reactive contacts and working along that spectrum, much like we would do with acceleration.

The biggest difference was talking about those technical points that crossover to what we are trying to achieve in the actual movement itself, and almost having these two components – teaching and training always in tandum. In the gym, adaptations taking a greater emphasis from a physiological standpoint and then equally out on the pitch, using velocity, and doing slow and fast movements to overload the technical and physical side.

One of the reasons why I like lateral shuffles and the importance of them, is that doing deceleration work (specifically 180 CODs) can be quite intense and really challenging to overload them, both from a physical capacity, or their ability to cope with those loads but also the time available to embed those teaching points. So the lateral shuffle was a great opportunity to still have some braking opportunity at lower velocities in positions that were really specific to what we want to see when we are doing deceleration in a 180 COD. So the lateral shuffle allowed us to have a lower hip height to start with which is what we want, and can we teach that individual to increase that touch down distance from a position of hip height that is already low, and the stick overhead keeps you accountable to having trunk discipline and keeping fairly upright. it’s a very good feedback tool to see whether you have trunk flexion involvement.”

”Let’s talk about transitional movements, I’d just like to hear more about what you see as transitional movements. As a defender in football, I was rubbish at them, so I’d like you to talk more about them. From your perspective, what are transitional movements?”

”I almost coin them the connectors between linear speed, braking and COD. It is the actions that take place between those movements. I think one thing that has been really pertinent for me and diving into this more and more, and that work started at my time at Chelsea FC, is a lot of that work was triggered by the football coaches. The background to that is that the coaches would come to me and say, ”he doesn’t move his feet very well, or he can’t change direction very well. But when we as a department looked at how we assessed those aspects, they were more traditional in terms of the 180 degree COD 10-5 test, or we would understand it in terms of a 90 degree cut, and they just weren’t crossing over with what the coaches were talking about. How we were assessing an athlete’s ability to change direction weren’t aligning and actually that pushed me a bit more to realise that there was more to it than just change of direction.

I think the reason why those transition movements are important is really because of the technical and tactical constraints of the sport. I think if you remove those aspects of the sport, I think linear speed, braking and COD are good enough, they tick the box. If we look at a sport like volleyball, there is a real need to keep your trunk facing the net while changing direction, and that is a tactical component of the sport, which then means that a lateral shuffle is going to be really important before you accelerate in order to keep yourself facing forwards. Or, if we are talking about a defender in football, there is a real need for him to stay facing the attacker, if he is running at him in a 1 vs 1, which is why a back pedal becomes important; if it wasn’t, then that individual would just turn and run, and it doesn’t need to be any more complex than that. So, I think it’s the presence of the technical and tactical constraints that highlights the need and importance of the transitional movements, that connect between linear speed, braking and COD.

The objectives of these transitional movements fall into three buckets for me:

- minimising speed loss when someone is changing direction or reorientation is needed – so for me that looks like someone going from a backpedal into a linear sprint. You’re still moving in the same direction, going backwards but I’m just changing my orientation. It doesn’t really fit into COD traditionally. So the requirements of that situation are how can I get into my backpedal and linear sprint without losing too much speed to keep my speed increasing, because I have a player running at me, for example.

- close or exploit space over small distances when change of directions are less effective – so similar to that volleyball situation, where a traditional COD like a 90-degree cut are less effective, and a lateral shuffle is going to be really important to close and exploit space.

- preparing for and accessing positions a lot quicker – if I can do a rotational step (drop step) providing that I am doing that effectively, I should be able to access key positions, have my hip height at the right place, decrease my touchdown distance and accelerate faster, when we are talking about linear speed.

Although I have categorized transition movements into four categories (lateral shuffle, rotational step (drop step), cross-over step and the back pedal) and it has been helpful for me to dissect and separate those movements into those four categories, one thing I have always been quick to check myself on is that I don’t train movement in just those isolated ways because when we work it back from the sport which is where they are highlighted, these actions do not happen in isolation. It isn’t just a lateral shuffle, it isn’t just a backpedal. It is commonly a back pedal into a lateral shuffle into an acceleration, or a deceleration into a drop step, into a re-acceleration. So for our understanding it is helpful to separate them into these areas, but when we go about training it is important to think about how these transitional actions present themselves in sport, and why, because there is probably going to be a need to mix and merge these movements whilst developing them.

It’s helpful to refer back to the levels in the Speedworks gamespeed framework, yes the four movement categories allow us a place to start to work on these categories in isolation. There is merit and value in understanding how well you backpedal just to backpedal (in isolation), because we know that when we combine these actions and look at the sport, backpedaling is a key component, for example. But we need to quickly understand that we need to move on to tasks that make things more representative of the game demands as we work through the levels and get closer to game speed.

It is not one movement solution for a situation. What is the objective of the task, and what is the most effective solution to achieve that? It is dependent on the technical, tactical and physical components that are involved in that situation, and not just this is the solution for the situation and I am going to use it.

”How do you then dissect things and then focus on that one transition movement, or perhaps you don’t, it’s more of a holistic view of things and it plays into lots of manipulation of these kinds of movements like we have just said?”

”Let’s take the situation of the central defender coming out to close down a striker who is then looking to run past them as coaches will commonly highlight defenders, as not moving well enough.

I’d definitely start by saying, ”what is the situation that you struggle in?” and for me that is definitely on the coach, definitely on the analyst (if you have those resources available) or perhaps my own understanding of the sport, and taking that real situation that is affecting performance. So maybe you’re not winning your 1 vs 1 battles or players are beating you too easily. That’s a real incentive to say, okay, we need to work on this, let’s highlight the situation you are struggling with and then dissect it – what are the speeds you are running at? What are the actions that are taking place? And what are the distances you are working in?

First of all I’m thinking, ”ok you clearly need to backpedal at quite a high speed as you need to keep facing the opponent, and then at some point you need to turn. Which aspect is it that you struggle with? Is it actually that you have a real loss of balance because you can’t backpedal effectively and that trickles into your turn and makes it look messy? Or actually is it you can backpedal really quick, but the moment I’ve asked you to do a rotational drop step, in order to turn and accelerate, maybe that is where yo have a loss of balance or a real drop in velocity, which works to the advantage of the attacker.

So highlight those points first of all, and then for me it’s about what are the key skills that take place in that moment? If it is the first portion of the backpedal then let’s isolate that, let’s overload it in different ways. Let’s see how well you backpedal across a 10m stretch. This is where the Project-Switch-Reactivity (PSR) Speedworks framework has been great for me because it works across many different aspects and it’s not just applied to linear speed.

So in that backpedal, can you project your COM in the right direction, can you switch your limbs to stay in control of your COM and can you be reactive on the floor? So, those are the things I would be looking at, and actually the bigger guys, you will probably see some strategies where they don’t really project themselves very far, they stay very tall and take loads and loads of steps but don’t travel anywhere! And actually, COM begins to topple over and the top half goes beyond their bottom half and lose their balance and maybe fall on their bum! In those situations there is merit and value in saying, I need to teach you how to backpedal better, so I need to teach you how to drop your COM better and project better, because you’re really good at switching but you’re just not getting anywhere.

From then on, I’m just going to use different types of techniques (differential learning) to play with direction, play with speed, to challenge the depth of situations with which you can execute this movement skill in various different ways because there is high variability when you go back to your sport. So how can I challenge it and stress test it before we go down the levels of 2, 3 and 4 of the gamespeed model, to make it more situation specific?”

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- COD is about how well do you brake and how well do you project outside of your base of support.

- Benefit of a polarized approach – helpful to understand opposite ends of the spectrum to get a good gauge of your strategies of doing everything else in between.

- Importance of a key teaching cue – sitting versus folding as you get in and out of the hole.

- Important role of anti and penultimate steps – a large part of our braking has been done in the anti-penultimate and penultimate contact, and the final foot contact is really to create a final block to decrease our forward momentum before helping us to project forward into the new direction

- Importance of transitional movements to gamespeed – lateral shuffle, drop steps, cross-over and backpedal.

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about?

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM

=> Follow us on Facebook

=> Follow us on Instagram

=> Follow us on Twitter