Some clarity around Trunk training

With the initiation of a third lock down in the UK we thought it would be a great idea to engage our readers in some motivating posts to help keep you motivated. We welcome back APA coach Konrad McKenzie with a weekly guest post.

This blog will be a follow on from my initial blog around training the core, it was inspired by a webinar I had listened to on “Trunk Training” kindly put together by Alex Wolf. I wanted to write about what I learnt on this talk in order to spread the word and create some real clarity on training the mid-section. I will mention some of the pertinent topics that Alex discusses and would like to stress that the issues discussed are from his presentation rather than my own. This blog, as the presentation was outlined, will be divided into several parts;

- Functional anatomy

- Trunk Function

- Why we need to consider the hip when talking about the Trunk

- Exercise classifications

- Exercise functionality and coordinative demands

Consider for a moment this picture of a bonnet. How much faith would you have in a car mechanic who did not know the parts of a car, could not identify what the problems were or the tasks that could be done to solve the problem? Funnily enough, not too long ago I broke down and had to rely on a car mechanic to solve an issue with my car. He did so meticulously.

Some questions that arose from the presentation were;

What does the trunk actually do when completing a task?

What do we have available to optimize trunk function?

When we can define the function of the trunk, we are able to align the most appropriate training methods we can to create real clarity of outcomes. This is something I believe the best practitioners out there have, clarity.

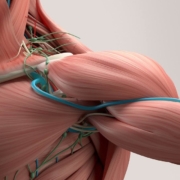

Functional anatomy

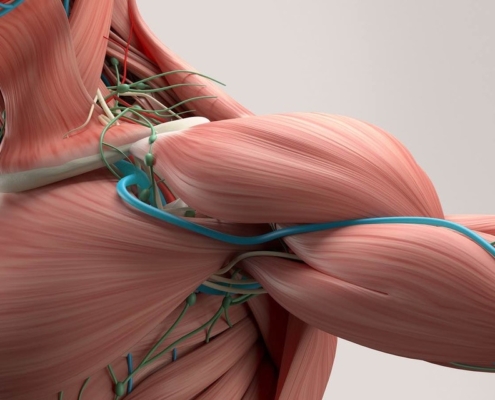

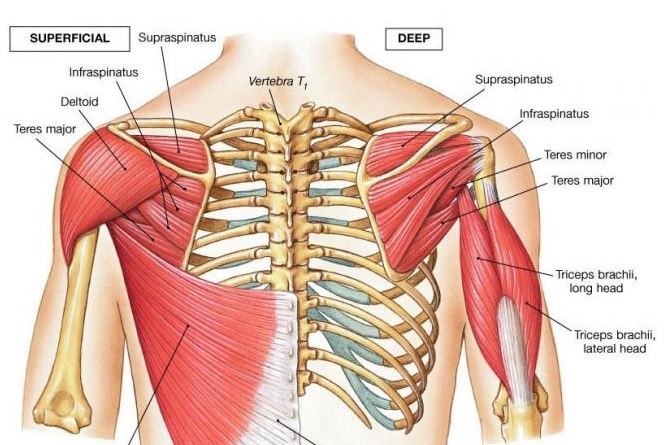

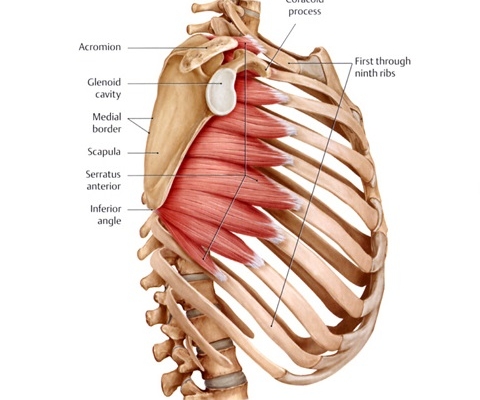

Similar to my blog around shoulder health I will break this blog down into two parts the Local and Global system. In the case of the trunk, both systems help to stabilise the trunk.

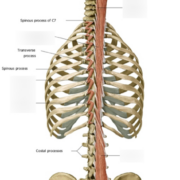

Local system

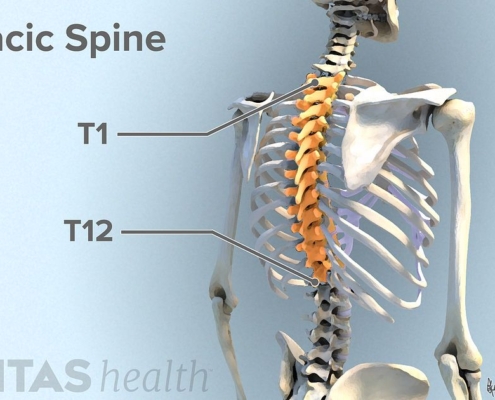

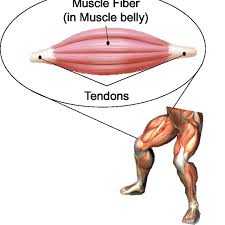

Local system is mostly made up of deep intrinsic musculature, which are attached closer to the vertebrae and are attached onto the spinal processes feeding into the ribs. The total volume of these muscles is small and (in terms of muscle architecture) are vertically orientated along the spine which highlights how the muscles operate and their force production capabilities. Muscles of the local system typically support spinal segmental control, are highly resistant to fatigue and anticipatory in nature (Feed forward mechanism). These muscles (to name a few) include the multifidus, Diaphragm and Pelvic floor and deeper fibres of the Erector Spinae. Structurally, the ligamentous (non- contractile) structures also provide segmental control and spinal stability. Historically, the term ‘Core stability’ came from spinal segmental control and the deeper intrinsic musculature.

Global system

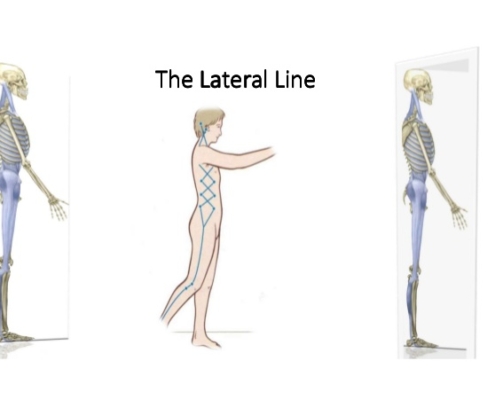

The Global system has larger more superficial musculature, which span many joint segments. Unlike the local system these muscles are more obliquely orientated thus, high force production capabilities and they initiate gross movement. Comparatively, the global system has lower fatigue resistance but this particular system provides stability and mobility to the spine. These muscles include the external/internal oliques, superficial fibres of the Erector Spinae and Rectus Abdominis.

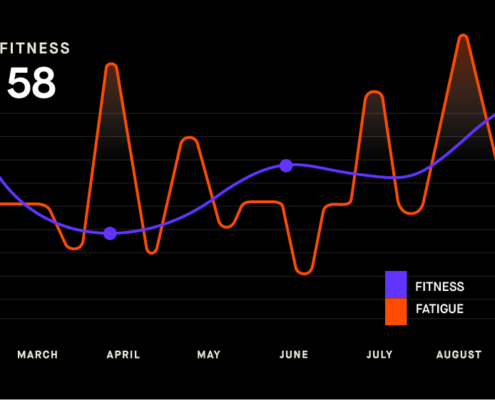

Trunk Function

Muscles of the Trunk produce force to serve a few roles. Particularly in Generation, Transfer and Control. I will briefly highlight these in more detail

|

Generation |

Transfer |

Control |

| · Rotation

· Block Rotation · Flexion and Extension · Lateral flexion and extension |

· Proximal to distal

· Lower to upper body · Posterior to Anterior · Medial to Lateral |

· Postural control

· Resist deformation to external and internal forces

|

Generation

This refers to the force generation capabilities, a recent topic of conversation in strength and conditioning is whether the trunk is designed to create/block rotation or both. Supporters of Block rotation suggest that the stiffening of trunk allows the arms and legs to work against it, rather than having a continuation of the movement which may dampen performance outcomes.

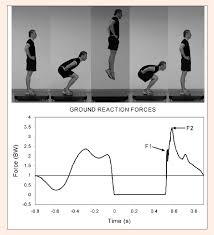

Transfer

Quite a common conclusion in strength and conditioning circles is that the trunk acts to transfer forces in athletic movements, through different planes of motion.

Control

Resisting deformation by external and internal forces, a useful example of external forces was a scrum in Rugby union as players have to manage external forces from the opposition. Internal forces refers to force that we ourselves generate.

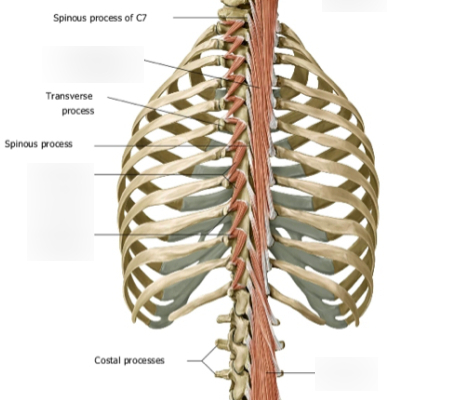

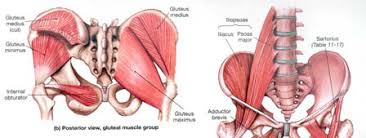

Why we need to consider the hip when talking about the Trunk

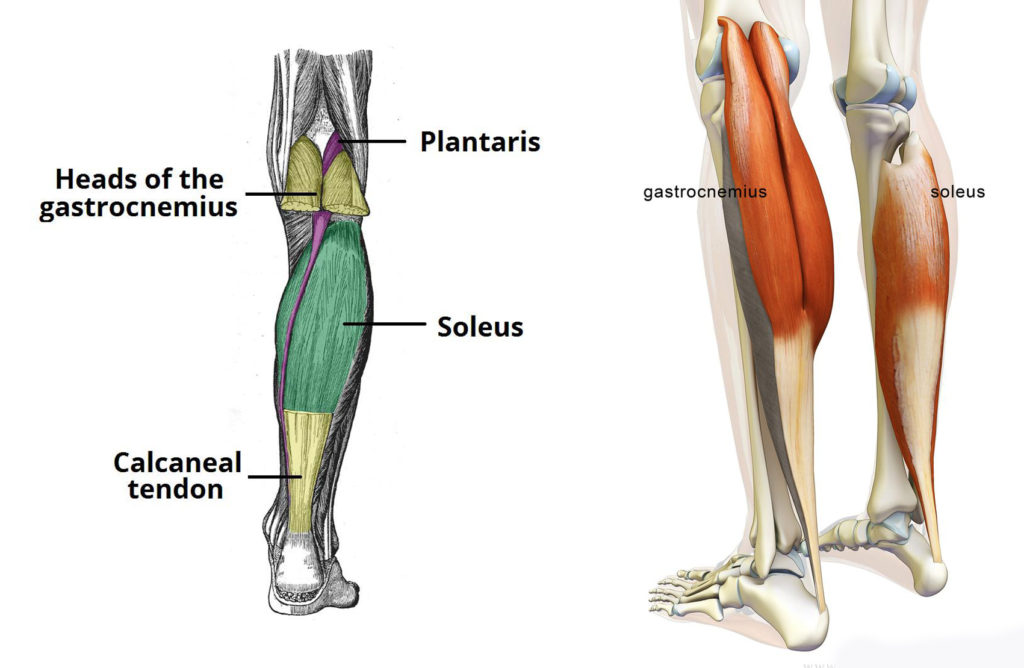

Some may have heard the term “Regional interdependence” the notion that all systems of the body are interconnected meaning that we cannot ignore the fact that large amount of abdominal muscles attach to the hip and pelvis. Therefore, dysfunction in the hips can lead to problems in the spine. Two notorious mal-alignments mentioned were posterior and anterior pelvic tilt. I will briefly describe anterior pelvic tilt as it’s the most prevalent issue I see.

Anterior Pelvic tilt (APT)

APT or lower crossed syndrome is characterised by a rolling forward of the pelvis due to shortening of the hip rectus femoris, Iliopsoas and the weaknesses of the deep abdominal musculature causing issues in the spine at the L4-L5 level.

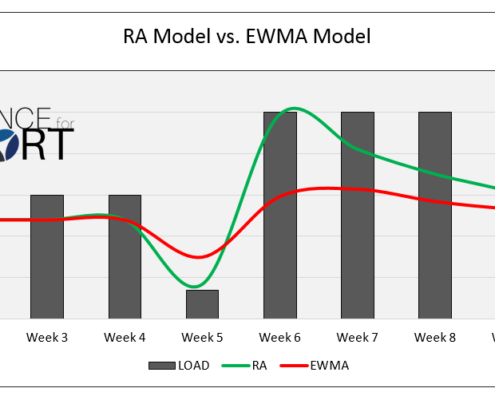

Exercise classifications

In this particular section I will not deep dive into everything that was mentioned, this blog would simply be too long. However, I am quite open to having conversations on this. What I liked about this presentation and paper is the clarity on the intention of each exercise classification, something I am going to use in my programming to add the extra layers of detail. The “what and the how”.

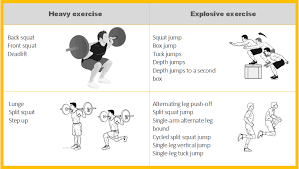

“Function is defined by its intended outcome, it is not how an exercise looks in relation to the performance task”

Alex has a great paper Spinal-Exercise Prescription in Sport: Classifying Physical Training and Rehabilitation by Intention and Outcome. The physical outcomes presented in his research were split up into four overarching qualities with further sub-classifications, which I will touch upon.

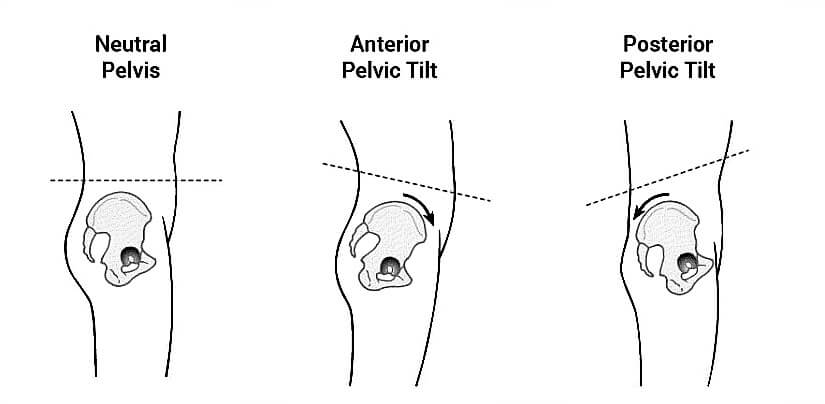

Just for the benefit of the reader the exercises were also further sub-classified described as functional and non-functional (NF). Functional (F) being exercises which allow their athletes to move in all planes of movement, for example a Squat. Non-functional exercises (example a side plank) are typically performed in partial weight bearing positions (single, lying kneeling etc) and across a single plane of movement (Spencer et al, 2016).

A) Mobility (F) and (NF) – Exercises used to develop, maintain, or restore global spine range of movement.

B) Motor control- referred to as the maintenance of spinal integrity during a skill movement task. This is not only a result of the capacity of muscles but also on the ability to process sensory input.

This was further subdivided into;

1) Segmental stabilisation (NF)

2) Spinal disassociation (NF)

3) Spinal disassociation (F)

4) Segmental movement control (NF)

C) Work capacity- The same as local muscular endurance, defined as the ability to tolerate varying intensities and durations of work.

This was further subdivided into;

- Pillar conditioning (NF)

- Pillar conditioning (F)

- Segmental conditioning (F)

- Segmental conditioning (F)

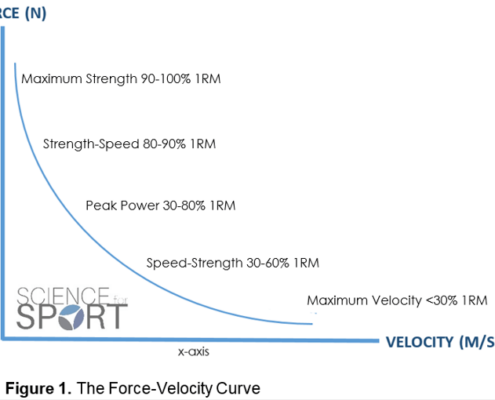

D) Strength- The ability for muscles to produce force.

This was further subdivided into;

- Pillar Strength development

- Stiffness development

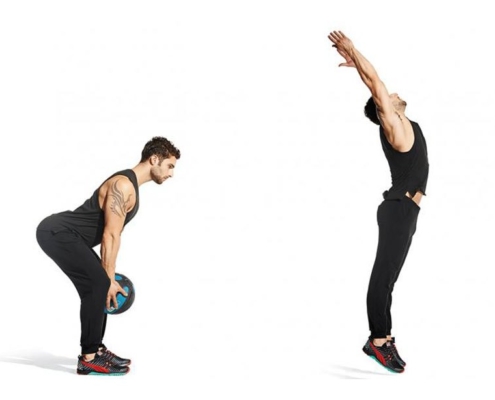

- Power development

As mentioned going into each sub-classification would be too lengthy and I will reference the article. However, I thought this was useful to organise exercise prescription by working backwards from the outcome!

Exercise functionality and co-ordinative demands

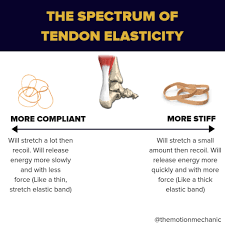

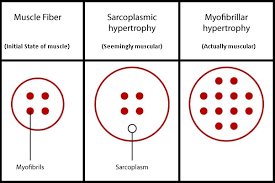

As part of Alex’s reflections on this paper he highlights an important topic “coordination” this is not going to be the usual way of thinking about coordination, but to describe it as truly functional to an athletic movement the muscle-tendon interaction of both tasks need to be identical, down to the;

- Magnitude of contraction (How much)

- Rate of contraction (How quick)

- Timing of interaction (When)

- Timing of interaction and contraction (How)

“Unless there is a real identical muscle-tendon interaction (coordination) between tasks, it cannot and never will be functional. Therefore functional, within the article should be redefined as F= Multi-jointed & NF = isolated”.

Interestingly, a point was made that the “Greatest success of achieving intended outcomes has been through NF exercises modalities”. Why? Because isolated exercises target specific tissues that need to be trained i.e. we are going directly to the horse’s mouth.

Thanks for reading this article, it was not intended to give you specific exercises rather an explicit framework for you to build your exercise program on.

Konrad McKenzie

Strength and Conditioning coach.

Reference:

Research Gate. 2021. (PDF) Spinal-Exercise Prescription in Sport: Classifying Physical Training and Rehabilitation by Intention and Outcome. [online]

Available at:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308533366_Spinal_Exercise_Prescription_in_Sport_Classifying_Physical_Training_and_Rehabilitation_by_Intention_and_Outcome> [Accessed 18 March 2021].

Liked This Blog?

You might like other blogs on this topic from APA:

APA review of the Middlesex Students S&C conference 2014

The Dubious Rise of the Corrective Exercise ”Pseudo-Physio” Posing as a Trainer- My thoughts

as well as two recommended articles:

This article on weak Glutes during Squatting

And this one on Exercise Modifications

Do you feel that this would be a perfect time to work on the weak links that you have been avoiding? The things that you know you should be doing that you keep putting off? Would you like us to help you with movement screening and an injury prevention program? Then click on the link below and let us help you!

? TRAIN WITH APA ?

Aspiring Pro Training Support Packages

Follow me on instagram @konrad_mcken

Follow Daz on instagram @apacoachdaz

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM