Supporting Female Athletes

With the initiation of a third lock down in the UK we thought it would be a great idea to engage our readers in some motivating posts to help keep you motivated. We welcome back APA coach Konrad McKenzie with a weekly guest post.

Supporting Female Athletes

This lockdown I have been fortunate to gain some more knowledge from leading practitioners in strength and conditioning & sport science. A few weeks ago I was enlightened by some great speakers at the “The Well HQ”. The topic was around female health and performance. This was pertinent to me, as I am a male coach who currently works with a large amount of female athletes. I wanted to share some insights from this talk to enhance the awareness around this topic. This blog will be a synopsis of the webinar but will also contain some of my experiences training young female athletes, which will hopefully create some provocative insights. The blog will contain the following topics:

- Knowledge gaps

- What we do know about training female athletes

- Menstrual cycles and how it can affect performances

- Potential Barriers to sport and engagement

- Steps we could take to support female athletes better

“80% of active women said they haven’t had enough education in relation to their body and how it affects their sport”- Dr Bella Smith.

What we do know about training female athletes

There is a great book the “female athlete handbook of sports medicine” which I encourage you all to read. This book is quite extensive so I will give a very brief summary on parts of chapter 1&2 that stood out to me.

Female athlete triad

The female athlete triad is defined as a spectrum of three interrelated medical conditions 1) energy availability, 2) menstrual health and 3) bone health (ACSM, 2007). These conditions range from optimal/healthy range to a pathological state of low energy availability, amenorrhea, eating disorders & osteoporosis. It is said that in order for female athletes not to suffer any components of the triad, it is paramount that they understand their energy needs and train and live in an environment which supports healthy energy availability.

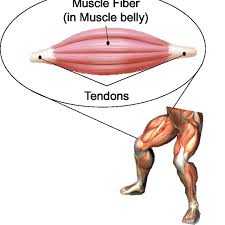

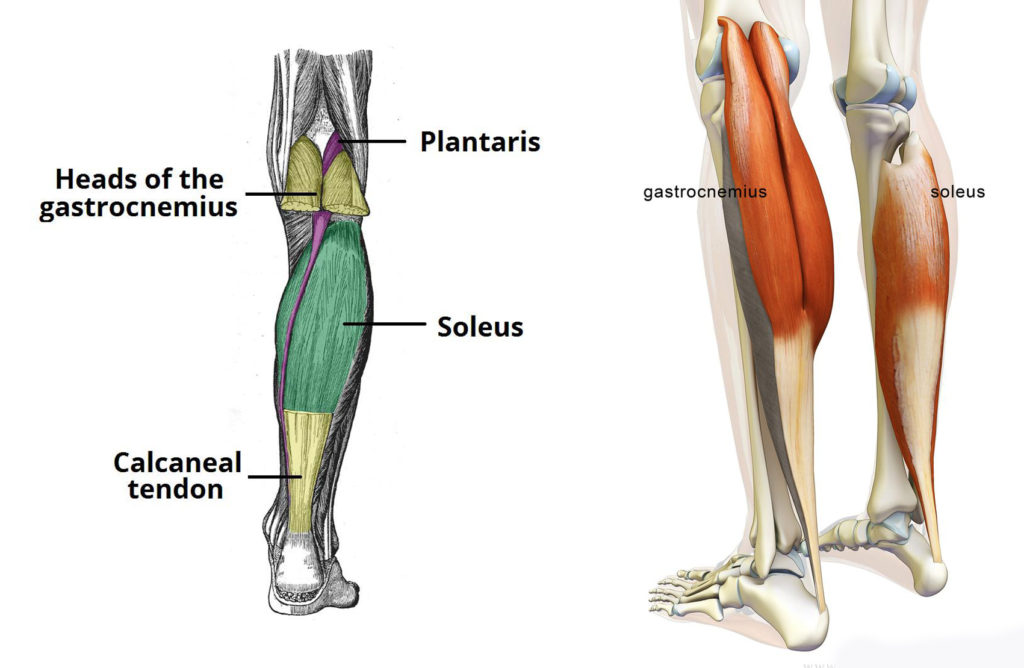

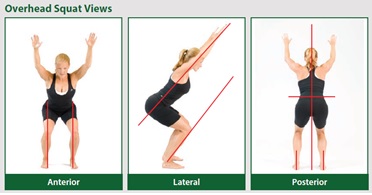

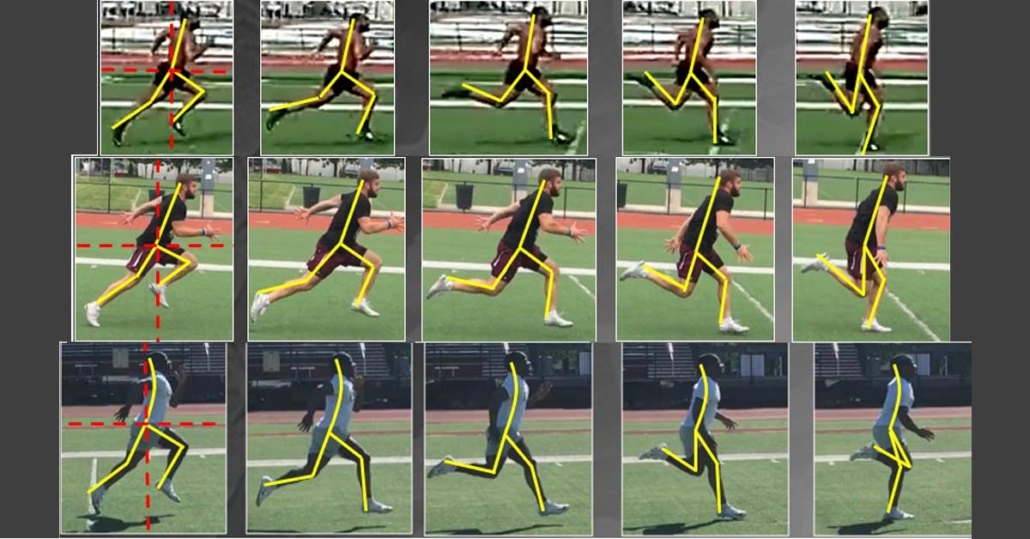

Non-contact ACL injuries

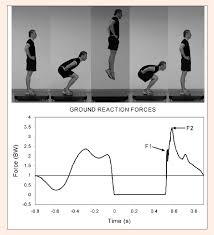

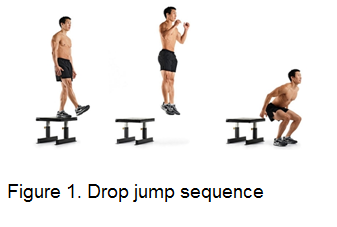

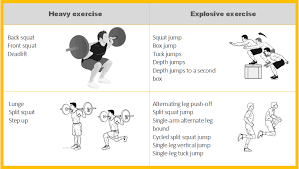

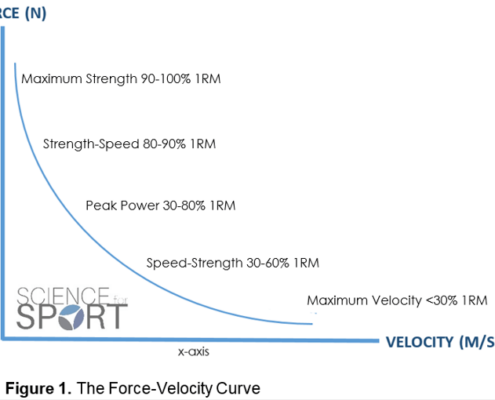

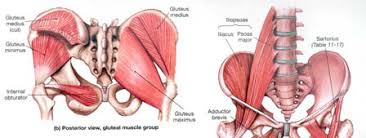

Female athletes are reported to have higher risks of non-contact ACL injuries. Interestingly, the research is trying to determine whether ACL injury is a result of gross failure of the ACL in one episode or multiple episodes over time. However, valgus of the knee and change in upper body trunk mechanics tend to be high risk factors for this. Although the research is said to be transient and the best intervention is not yet identified, changes in dynamic loading, proprioceptive training and sound coaching go a long way in mitigating these risk factors. Training programs containing a healthy dose of strength, power, plyometric and neuromuscular training, seem to have promising results.

From the Well HQ talk it was said that women are 4.5 times more likely to sustain an ACL injury. Although the skeletal structure and the anatomy of pelvis is non- modifiable, factors such as muscle imbalance, proprioception and landing mechanics can be trained.

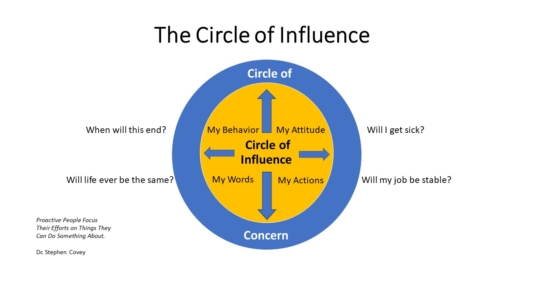

Knowledge gaps in coaching female athletes

The aforementioned quote is alarming right? A high proportion of female athletes still to this day are not educated enough about their bodies. Why? It was suggested, that there may still be a reluctance to talk about it, due to feeling ashamed or embarrassed. Whilst this is perfectly understandable, the more we communicate about this the easier it will become.

“Trust takes years to build, seconds to break and forever to repair”

Gaining trust is vital for clear communication pathways especially about sensitive subjects so this quote is important to bear in mind. Furthermore, I would like to note that it is important not to take offence if a female athlete does not immediately open up to you about what she is experiencing, this is a delicate manner thus, it is important to guide her to someone she feels more comfortable talking too. Women, unlike men, appear to value the quality of a relationship as opposed to the quality of a coach, meaning you have to take the time to cultivate and nurture the relationships you have with your female athletes.

In my experience, I had a young female athlete who was going through her first menstrual cycle, you can imagine this was very troubling and awkward for her to mention. So she just gave me a sign and then I took the hint, to adjust certain exercises for her. Now whilst this is not very “scientific” it lead the way for her to download an app, which allows me to see when she’s entering that phase. A pretty huge breakthrough if you ask me. More on this in “Steps we could take” Section

Lastly, the women at Well HQ gave another profound statistic. I was pretty shocked about this myself. As little as 4% of sports science research is done on women only. Moreover, they had mentioned that the 70% of research done on mixed groups fails to control for the changing physiology and psychology during the menstrual cycle.

Performance and the menstrual cycle

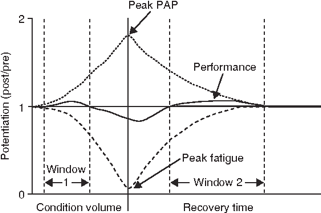

The team mentioned that a 28 day hormonal cycle can really affect a woman physically and emotionally. From a performance perspective an elite 1500m runner with a 4:03 minute time could, on the day before (or on the same day of her period) run the same event in 4:15 minutes. That’s a colossal difference. Interestingly, determinants of performance such as VO2 max, running economy, strength and power are not significantly affected during a healthy cycle. However, how a woman feels emotionally and physically fluctuates as her hormones change. As a result, this challenges her ability to tap into peak performance.

It is known that having a period is a healthy sign of bodily function and health. On the other hand, 30% of female athletes lose their cycle at some point. To give an illustration of how significant this is, lack of periods meant a promising runner did not produce enough oestrogen (An important hormone in the cycle which aids bone strength) and thus developed osteoporosis in her 20s.

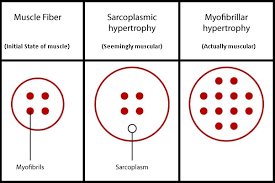

Interestingly, Oestrogen creates a great physiological environment for muscle growth and repair. So much, that strength gains in the first half of the cycle can improve by 15%.

Potential Barriers to sport and engagement

I wanted to share some barriers to sport and engagement which, perhaps, is overlooked by trainers, coaches or Teachers.

Bras

It was mentioned that 80% of female athletes had poorly fitting bras. Furthermore, ahead of the Tokyo Games 72% had reported pain in training as a result. A poorly fitting bra can have significant effect on performance by up to 4% which is large at the elite level, where margins are thin. On the engagement side it was said that 33% of women with a cup size of D or above say they don’t exercise because of their breast size

Pelvic floor

It is common knowledge that pelvic floor issues affect older and post-natal women. However this is not the only category of women it affects, it also affects athletes. Leaking urine during training and competition as a result of pelvic floor issues (even in women who have not had babies) is quite common in high impact sports such as trampoline, sprinting or basketball. Pelvic floor dysfunction is an understandable barrier to sport. Positively, this can be rectified by including gym based pelvic floor exercise.

Steps we could take to support female athletes better

I wanted to share some ideas in how we could support our female athletes better, this is not an exhaustive or very descriptive list however I wanted to create some discussion and more awareness around this area.

Education

With such a large amount coaches and females themselves not knowing their own bodies, the first stage is education. However, educating is nothing if we do not create a safe space for female athletes to speak out and share what they are going through.

Monitoring the menstrual cycle

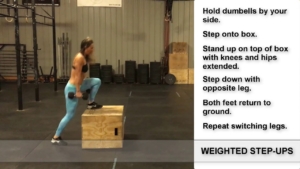

There are many apps out there including Clue, Flo and Eve. Although collecting this data is sensitive it would be great if we got to a stage where we had this information on the female athletes we worked with and tailored workouts accordingly in every club or academy. For example, focusing on strength and reducing the volume in speed and plyometric training during certain stages of the menstrual cycle.

Environment

As alluded to in the first paragraph, creating a safe space also means creating an environment where there is no scarcity in items such as sanitary towels or menstrual cups as an example. If this is evident in academies then I believe this will positively add to female athletes being comfortable enough to share their feelings.

Training

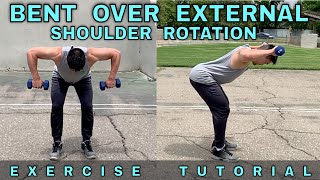

I will not go into this in too much depth as there is a lot of great work out there. Conditioning programs will have to address the areas of proprioception, muscle imbalance and strength to serve the needs of the female athlete better. It may be, that we spend longer in phases that address these qualities and spend more time to focus on things like landing mechanics and single leg squatting.

“Check, Challenge, Change”

Thanks for reading guys,

Konrad McKenzie

Strength and Conditioning coach.

Liked This Blog?

Find out more about Female Health at the Well HQ

Do you feel that this would be a perfect time to work on the weak links that you have been avoiding? The things that you know you should be doing that you keep putting off? Would you like us to help you with movement screening and an injury prevention program? Then click on the link below and let us help you!

? TRAIN WITH APA ?

Aspiring Pro Training Support Packages

Follow me on instagram @konrad_mcken

Follow Daz on instagram @apacoachdaz

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM